Cairo University in Cinema: Reflecting Dreams, Divisions & Identity

We look back at how Cairo University has turned into a cinematic symbol of Egypt’s fractured dreams, enduring struggles, and evolving national identity.

Cairo University has long transcended its role as an academic institution in Egyptian cinema, evolving into a profound symbol of the youth’s ambition, struggle, and the collision between their dreams and reality. Its iconic halls and lively campus have served as a narrative lens through which generations of filmmakers have explored Egypt’s societal aspirations and the unrelenting forces that often subvert them.

Cairo University’s prominence in Egyptian cinema emerged during the Nasserist era, when the nationalisation of the film industry and the wider access to education positioned it as both a symbol and a tool of the state’s vision for progress, intertwining its identity with the aspirations of a modernising nation.

Across decades, Egyptian cinema has returned to this setting, transforming it into a stage where stories of intellectual pursuit, class mobility, and the painful truths of modern Egypt unfold. Slowly, Cairo University’s cinematic story has mirrored the arc of Egypt’s modern history.

1950s: A Symbol of National Ambition & Class Struggles

During Egypt’s post-revolutionary Nasserist era, Cairo University became a cinematic embodiment of national ambition. Films of the 1950s depicted the university as a crucible for societal transformation, making it a beacon of hope, an arena of resistance, and a stage for Egypt’s evolving identity.

Films of the 1950s often portrayed university students as the intellectual elite, carrying the weight of Egypt’s dreams for independence and modernization. Admission was fiercely competitive, requiring exceptional academic prowess or significant influence, making the institution both exclusive and prestigious. For many, the university represented a gateway to opportunity, respectability, and empowerment. In ‘Ana Hurra’ (1959), Amina’s (Lubna Abdelaziz) pursuit of education symbolized defiance against entrenched societal norms, positioning the university as a gateway to personal liberation.

Cairo University was portrayed as a bastion of discipline and decorum, embodying the era's deep respect for education as a transformative force. In ‘Bent 17’ (1959), this is vividly illustrated when Safaa (Zubaida Tharwat) is chastised by her professor for wearing nail polish, underscoring the university’s role as a space where modernity coexisted with steadfast academic and societal norms.

However, this idealism often carried undertones of exclusion. While Cairo University was portrayed as a space of opportunity, it remained out of reach for many. Films such as ‘Rodd Kalby’ (1957) highlighted this divide, where Ali (Shukri Sarhan), a gardener’s son, dreams of entering the university but is barred by financial constraints and lack of connections. These narratives unveil a profound paradox: education served as a beacon of progress while simultaneously exposing the persistent barriers of class inequality.

1960s: A Symbol of Romantic Freedom & Modernity

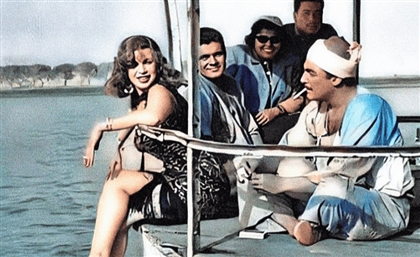

In 1960s Egyptian cinema, Cairo University emerged as a powerful symbol of societal transformation, embodying newfound freedoms that allowed students to interact across genders and challenge traditional norms, such as arranged marriages. This cultural shift was vividly depicted in films like ‘Abi Fawk El Shagara’ (1969), where university life became a metaphor for youthful independence and unconventional relationships, and ‘El Bab El Maftouh’ (1963), where Laila (Faten Hamama) received love letters on campus, reflecting the changing social attitudes toward romance.

However, this newfound freedom was balanced by the university's structured and disciplined environment, which mirrored Nasser's vision of national progress. Campus life was portrayed as a microcosm of collective ambition and unity, where orderly routines and shared spaces symbolized a society striving for modernization and harmony.

The 1970s: A Symbol of Division & Resistance

As Egypt shifted from Nasser’s socialism to Sadat’s open-door policies, Cairo University’s portrayal began to fracture, reflecting growing economic disparities and political unrest. In films like ‘Al-Karnak’ (1975) and ‘Al-Arafa’ (1981), the campus became a site of surveillance and oppression, illustrating the state's crackdown on student activism during the Nasser Era. This shift marked a departure from earlier depictions of the university as a space of collective aspiration, replacing it with an atmosphere of resistance, distrust and disillusionment.

Sadat’s open-door policy introduced profound economic disparities that reshaped the dynamics of university life, a transformation vividly captured in Egyptian cinema. Cairo University, once a symbol of collective aspiration, was now portrayed as a fractured space where the divide between wealthy and underprivileged students became starkly visible. In ‘Khali Balak Men Zouzou’ (1972), Zouzou (Soaad Hosny) becomes the centre of controversy, her mother’s work as a belly dancer sparking debates among peers. While some demanded her exclusion, others defended her right to education, framing the university as a contested ground for debates on social mobility and class prejudice.

The shifting economic realities also altered campus interactions, replacing the structured decorum of earlier decades with a more informal and fragmented social dynamic. Romantic relationships, once idealised in the cinema of the 1960s, began reflecting the complexities of society. In ‘El Hafeed’ (1974), young couples like Shafik (Nour El-Sherif) and Nabila (Mervat Amin) struggled to balance academic ambitions with marital obligations, highlighting the personal sacrifices and growing disillusionment of the era. Through these narratives, the university became a microcosm of a nation grappling with change.

The 1980s: A Symbol of Disillusionment

The 1980s ushered in a darker, more sobering depiction of Cairo University, reflecting its decline under systemic pressures. Films portrayed it as an institution weighed down by overcrowded lecture halls, deteriorating infrastructure, and disengaged faculty. In ‘Ana La Akdeb Lakenni Atagamal’ (1981), Ibrahim (Ahmed Zaki) embodies this disillusionment, his academic success overshadowed by the lingering shame of his modest origins. This era dismantled the university's once-romanticized image, offering instead a stark and unflinching portrayal of a system failing to fulfill its promise of social mobility.

The 1990s and 2000s: A Symbol of Cynicism & Survival

The 1990s and 2000s cemented Cairo University’s role in Egyptian cinema as a stark symbol of systemic failure and growing societal disillusionment. Neoliberal reforms, privatisation, and widening economic disparities fundamentally altered the narrative of university life, shifting its depiction from one of ambition and progress to one of mere survival. Films from this era painted a bleak reality, where education became increasingly transactional, privilege trumped merit, and the university mirrored the broader inequalities fragmenting Egyptian society.

Class divides took centre stage in these narratives. Wealthier students, armed with resources and connections, were juxtaposed against their underprivileged peers, struggling to navigate both academic and social spheres. In ‘The Yacoubian Building’ (2006), Taha, portrayed by Mohamed Emam, embodies this alienation. As the son of porters, he finds himself isolated among peers whose families wield influence in ministries and global organizations. He comments, “If they knew that the grade coordination office brought together the sons of porters and shoemakers with the sons of United Nations officials, they would have shut it down.” This is a poignant critique of the entrenched classism that pervades university culture during this period.

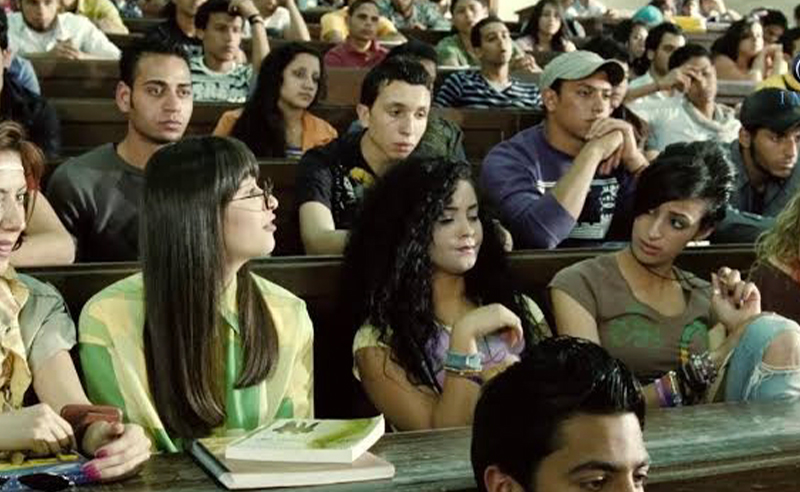

The university’s focus shifted further away from academic rigor and activism, becoming instead a venue for escapism and superficial connections. Films such as ‘El Hob El Awel’ (2001) and ‘Kalem Mama’ (2003) portrayed students lounging in lecture halls or using the campus as a space for socialising rather than intellectual engagement. Similarly, ‘Hob El Banat’ (2004) and ‘El Thalatha Yashtaghaloonaha’ (2010) depicted universities as platforms for networking or marriage prospects, reflecting a growing detachment from the ideal of education as a transformative force.

This is extended to the university’s political role. Campuses became platforms for ideological recruitment, like the Muslim Brotherhood. Films like ‘The Yacoubian Building’(2006) and ‘Hassan wa Morcos’ (2008) highlighted how universities became arenas for political influence, mirroring the broader ideological fractures within Egyptian society.

By the mid-2000s, Cairo University’s cinematic image reached its lowest point, reflecting a profound societal dissatisfaction with the state of public education. Many films shifted their focus to private universities, portraying them as the new epicentres of student life. Movies like ‘Morgan Ahmed Morgan’ (2007), ‘Omar w Salma’ (2007), and ‘El Basha Telmeez’ (2004) framed these institutions as symbols of exclusivity and consumer-driven education, reinforcing the notion of learning as a commodity.

Through this lens, cinema not only documented these disparities but also delivered a sobering critique of a society grappling with its eroding values and fractured aspirations.

- Previous Article Age for Trading on the Egyptian Exchange Lowered to 15

- Next Article Six Unexpected Natural Wonders to Explore in Egypt

Trending This Week

-

Dec 23, 2025