Rania Hussein Amin Writes Children's Books for Kids, Not Parents

The author of 'Farhana' is currently nominated for the Hans Christian Andersen Award for Children’s Literature for her work in realist children's literature.

I attended an online seminar with Arabic children’s book author and illustrator Rania Hussein Amin, at the height of quarantine in 2020, because I saw a Facebook event announcement by Diwan Bookstore, and because I was very bored. I logged into the Facebook live and watched Amin talk about her career, her process, and the need for children’s literature. She seemed as nervous as someone who’s just had their first book published, despite having spent two decades in the industry at the time, and like someone who’s still figuring it out. She said she believed nearly anyone could write for children. I was instantly charmed, and she since became a name I regularly searched for at bookstores - for both my little brother and myself.

This year, Amin was nominated for the Hans Christian Andersen Award for Children’s Literature, a biannual lifetime achievement award that is considered the highest global distinction a children’s book author can receive, widely known as the Nobel Prize of children’s literature. When we met for this interview, Amin spoke about the nomination with the same distant casualness she spoke at the online Diwan seminar, expressing little hope for winning in 2026, despite having produced over 52 titles over 25 years, and winning multiple regional awards.

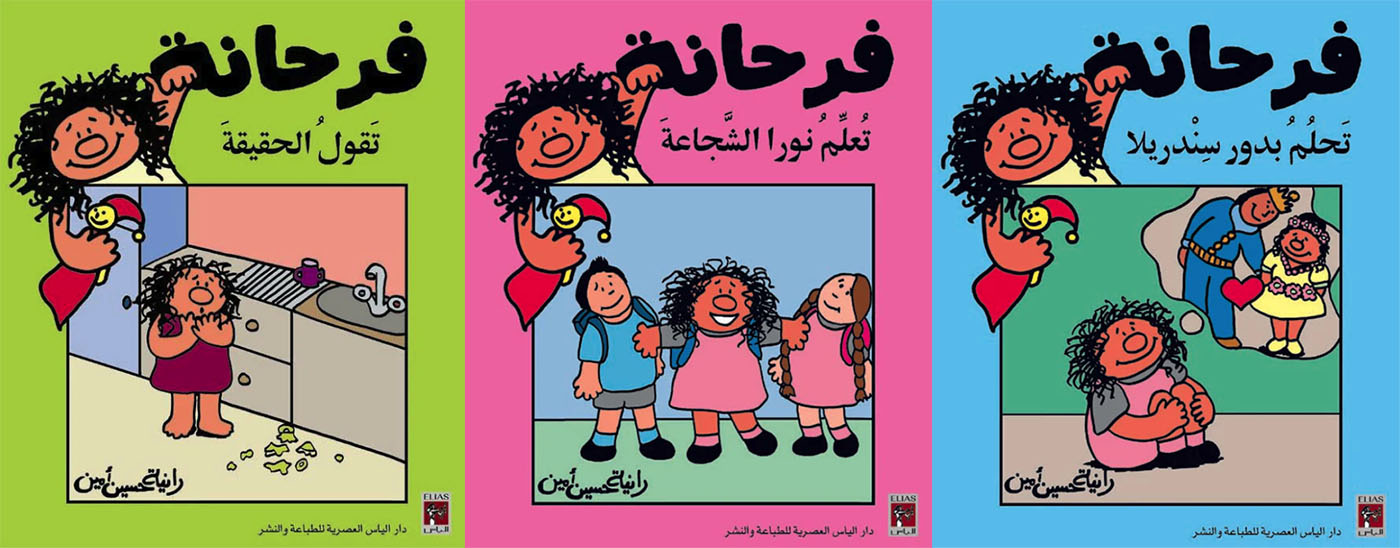

Amin’s most popular, and most awarded, work is her picturebook series 'Farhana', in which the titular Farhana - a young, unruly, barefoot girl - is narrated through different scenarios. The first batch of 'Farhana' books, twelve 12-paged books, follow the heroine through pretty ordinary events in school and home, illustrating the feelings every child goes through and the lessons their parents want them to learn: don’t lie, share, be brave (to a limit!), and so forth. 'Farhana' was written and illustrated entirely by Rania. “I wanted to illustrate 'Farhana' because I wanted her to feel honest," Amin tells CairoScene. "I drew her to look characteristically Egyptian. She has curly hair, she has a big nose, her features aren’t really that accentuated. I considered giving her braids, at some point, but Farhana’s defining characteristic is her freedom, so I let her hair down. I intentionally made her not pretty, because that’s really irrelevant to her character, and I didn’t want the girls reading to think of her as that.”

'Farhana' was written and illustrated entirely by Rania. “I wanted to illustrate 'Farhana' because I wanted her to feel honest," Amin tells CairoScene. "I drew her to look characteristically Egyptian. She has curly hair, she has a big nose, her features aren’t really that accentuated. I considered giving her braids, at some point, but Farhana’s defining characteristic is her freedom, so I let her hair down. I intentionally made her not pretty, because that’s really irrelevant to her character, and I didn’t want the girls reading to think of her as that.” Reading 'Farhana' is, as Amin intended, very real. The character is truly devoid of any physical or aesthetic significance beyond what she chooses to do, like the book where Farhana rips off her dress after feeling physically constricted in it (published in 2007). I discovered 'Farhana' as an adult, but I imagine a world where, having grown up with her, I would think of my (also characteristically Egyptian) appearance as normal. A world where I wouldn’t pray my future children don’t end up with curly hair like mine; a world where my appearance is simply something I don’t really make note of.

Reading 'Farhana' is, as Amin intended, very real. The character is truly devoid of any physical or aesthetic significance beyond what she chooses to do, like the book where Farhana rips off her dress after feeling physically constricted in it (published in 2007). I discovered 'Farhana' as an adult, but I imagine a world where, having grown up with her, I would think of my (also characteristically Egyptian) appearance as normal. A world where I wouldn’t pray my future children don’t end up with curly hair like mine; a world where my appearance is simply something I don’t really make note of.

After the first collection, Amin realised the classic, drawn-out moral lessons of children’s books weren’t really what she wanted to say, so she convinced her publishers to let her tell bigger stories. “I’m a very opinionated person, and I wanted a space to speak about the things that mattered to me and introduce children to these 'bigger' topics.” So Farhana explored the ethicality of zoos, beauty standards and how to listen to her friends. As they expanded, Farhana’s stories still existed within the realm of realism. within a world children could actually explore. “25 years ago, most Arabic children’s books were rooted in fantasy, which could be interesting to people, but it wasn’t to me," Amin says. "It felt like we were creating too big a difference between the children and the world they actually lived in. The books that existed in our world sounded more like lessons than stories.” Because Amin didn’t grow up in one place - she constantly moved from country to country with her family - she developed the detached observation necessary for her to accurately draw up real stories.

'Farhana' is where Amin began, but it’s not where she ends. “Farhana isn’t me, and she isn’t my daughter. Farhana is sort of the person I wanted both myself and my daughter to grow up to be: free.”

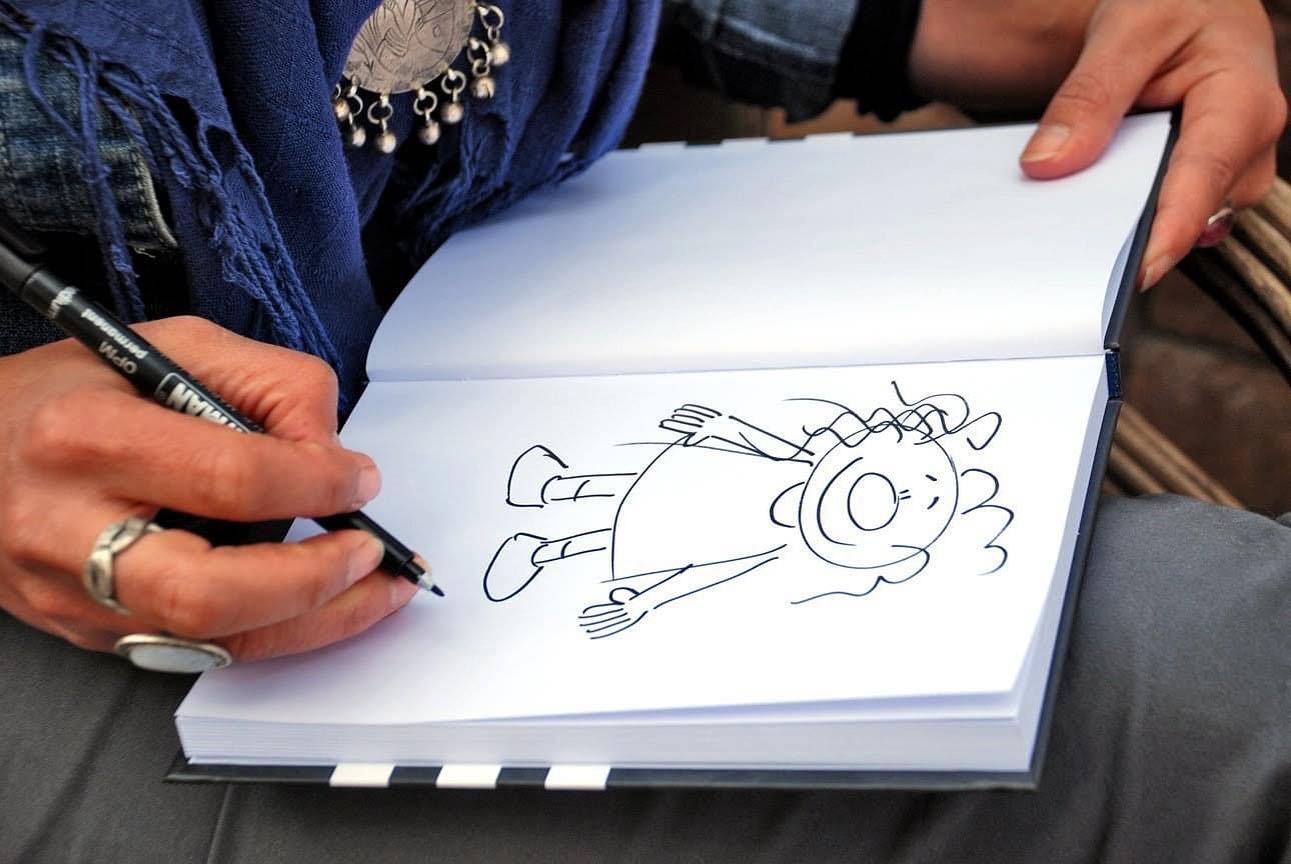

Before 'Farhana', Amin worked a bunch of odd jobs. She graduated with a bachelor’s in psychology from the American University in Cairo, at which time she regularly wrote short stories about her observations of her life and the lives of her friends, several of which later went on to publishing. She also dabbled with art (and continues to; at our interview, she wore a necklace with a papier-mache pendant she made and painted), and exhibited her work at multiple exhibitions. She worked in publishing, and taught in classrooms, and was a school counsellor. In retrospect, it seems as though the trajectory of her career constantly hovered around her eventual becoming a children’s book author, which finally happened when she attended a panel where one of the speakers talked about telling stories for children.

“I never thought of it as something I could do, but, at that workshop, I was almost bombarded with a flow of ideas. I immediately wrote down ideas for multiple books and even began loosely sketching.” Since they sprouted, Amin’s ideas have flowed abundantly - she describes the process as a “strong need to get ideas out” - so much so that she struggled with publishers asking her to slow down and use fewer pages. When she gets an idea, Amin lets it simmer for a while, giving it time to change and ferment, then records it. The writing and illustration processes mingle, as the excitement of each gradually overpowers the other.

“The sad truth is that when it comes to book shopping, at a fair, for example, parents often opt for the less expensive option, regardless of content," Amin shares. "If your books are longer, they cost more, and they’re less likely to be bought, which never translates well with publishers.” The question of accessibility is one of a number of issues plaguing children’s literature in the region. While financial accessibility to books is beyond a writer’s scope, the public’s understanding of the importance - or insignificance - of the books is something a writer can achieve.

“It really helps to do readings, at schools or publishing houses. In my experience, school readings not only benefit the kids, they benefit the writer too,” Amin says. When asked what else the children’s literature in Egypt needs, she says, “Less explicit messaging, more competition, more authors and illustrators, and general awareness - perhaps through marketing - so that parents know what to buy.”

Amin also references a need for criticism as necessary to the industry’s growth. Authors can write whatever they want, in order to please the parents and make sales, and publishers mostly care about whether or not books sell. In between them, no one ensures that the books on the shelves actually benefit our children. On the other hand, accessible criticism enables parents to develop the awareness to know what they want to be on their kids’ shelves.

At 60, Amin is nowhere near done with the books she wants to write. Her ideas still flow with the same pressing necessity, and she continues to produce books for children, teenagers and adults. Her most recent book, a graphic novel she wrote and illustrated depicting the lives of people who find themselves in a therapist’s office on one day, takes on an entirely novel direction from her previous work, one she’s excited to explore.

In the world of children’s literature, Amin still sees gaps: in writing for children, and not to please parents; in writing on our planet, and in writing for children with special needs, who currently have no representation in Arab children’s literature. Amin currently spends her days crafting, observing and refusing to slow down.

- Previous Article At The King’s Feast The Nile Flows Through the Grand Egyptian Museum

- Next Article Hype: The Egyptian AI Hangout App Built by Users