The Saudi Novelist Reimagining Regional History Through Sci-Fi

For Ashraf Fagih, Arabic sci-fi isn’t just an imaginative exercise, it’s an instrument for reshaping how we understand time, memory and meaning.

In the MENA region, as across the globe, 2025 feels like a defining juncture; an uncertain void where the lines between past, present, and future blur. As we navigate the complexities of the digital age, we find ourselves not only existing within this void but desperately seeking to make sense of it. The once fantastical elements of science fiction are no longer distant imaginings but have become interwoven with our reality as human voices and those generated by algorithms are becoming increasingly indistinguishable.

What does this juncture mean for the Arabic science fiction genre? With the once unimaginable now woven into the fabric of everyday life, does sci-fi and speculative fiction lose its relevance, or does it take on a new significance? In regions like the Gulf, where AI breakthroughs dominate headlines and futurism is deeply embedded in societal discourse, science fiction is no longer a mere genre, it’s an integral lens through which we understand our history and the possibilities that stand before us.

Ashraf Fagih, a Saudi academic and novelist, has spent his life living between Saudi, North America and China and has spent much of his career exploring the intersection of science, history, and speculative fiction. Fagih holds a PhD in Computer Science and is one of very few prominent voices in Arabic science fiction.

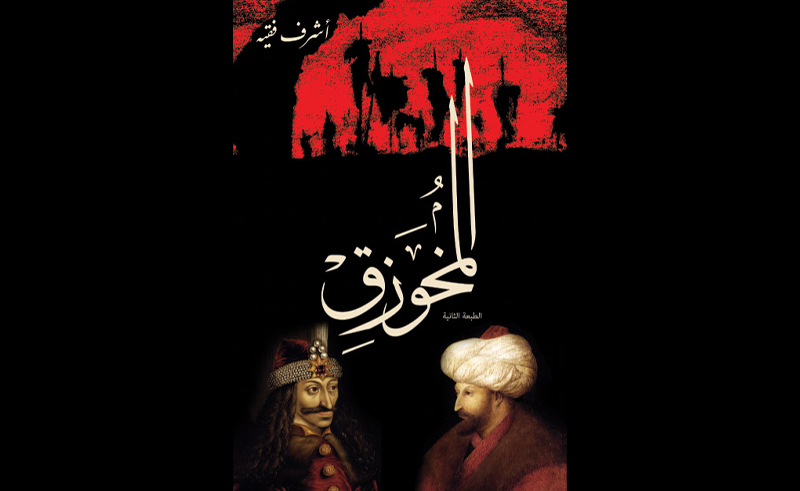

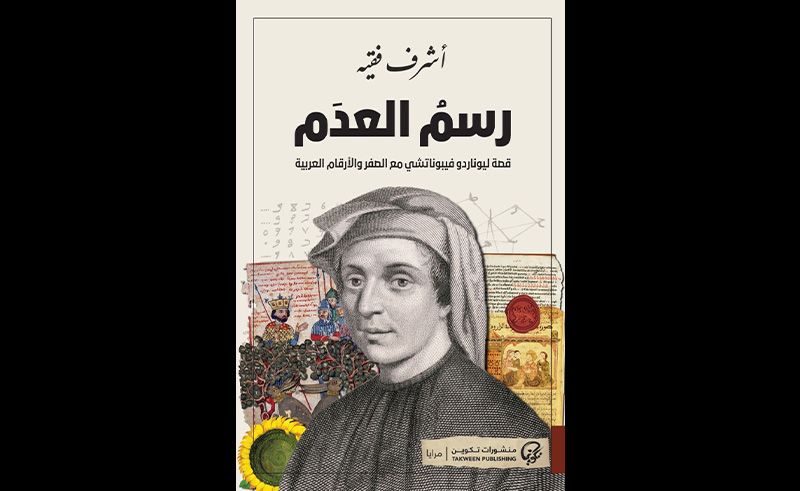

Fagih's literary journey began at the age of 20 with the publication of his first science fiction short story collection, ‘The Ghosts’ Hunter’ (1997). He continued to explore speculative themes in subsequent collections like ‘Longing to the Stars’ (2000) and ‘Over Twenty Lives’ (2006). He then shifted from sci-fi to historical fiction. ‘The Impaler’ (2012) delves into the Eastern origins of the Dracula legend, focusing on Count Vlad Dracula's 15th-century struggle against the Ottomans. His most recent novel, ‘The Portrait of the Void’, explores the life of 13th-century Pisan mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci and the introduction of the Arabic numeral system to Europe.

Fagih spoke to SceneNowSaudi about the evolving meaning of sci-fi and speculative fiction and its growing importance in the age of AI for the MENA region.

Can you tell me about your background and how you found your way into writing Arabic Sci-Fi and speculative fiction?

Can you tell me about your background and how you found your way into writing Arabic Sci-Fi and speculative fiction?

Fagih: Writing has always been a natural aspiration for me, as I was surrounded by books from a very young age. Both of my grandparents had extensive libraries, and they came from families deeply invested in education and learning. The act of writing has always fascinated me.

I grew up in a time when ideological currents were strong. There was constant talk about the Islamic Ummah and the lost glory of our civilisation. We were encouraged to revive this past greatness. In some sense, this led me to think about what it meant to contribute to a kind of intellectual revival, and in a way, it steered my mind, like a processor, to the genre of science fiction.

I was drawn to writing something different. Science fiction in Arabic was practically unheard of. I was inspired by films and, certainly, I was influenced by Nabil Farouk and Ra’ouf Wasfi’s works. I started writing at 17 and had my first collection of short sci-fi stories published at age 20.

For me, being interested in history and science come together. I studied computer science at university and also became interested in history because I thought that this would be the way to contribute to the nahda of my nation.

Now, 30 years later, my passion for science fiction remains strong. I write not only out of personal interest but out of a sense of duty. The genre is still underdeveloped in Arabic literature - there are no Arabic masterpieces in science fiction yet, and this is something we need to address.

Arabic science fiction has historically been far less prominent than its English-language counterpart. Why is that, and how is it changing in the digital age? What does it mean to write science fiction in Arabic?

Arabic science fiction has historically been far less prominent than its English-language counterpart. Why is that, and how is it changing in the digital age? What does it mean to write science fiction in Arabic?

Fagih: Science fiction as a genre emerged in direct response to the Industrial Revolution in the West. It grappled with the upheavals that came with that era: class division, capitalism, Marxism. Even the word robot comes from the Czech robota, meaning forced labour. At that same historical moment, the Arab world was focused on something very different: fighting for independence from colonial powers. So while science fiction gained momentum in the West, it didn’t take root in our region.

Later, the two World Wars, essentially technological wars, strengthened the bond between humanity and machines, giving sci-fi another major boost. But again, the Arab world was focused on something different: fighting for independence from colonial powers. Then came the atomic age, the space race, and the philosophical shift away from religion towards science. These cultural and historical currents didn’t affect our societies in the same way, or at the same scale.

There’s also the issue of language. The vocabulary of science fiction, words like microchip, warp drive, intergalactic empire, simply didn’t exist as eloquently in Arabic. It made engaging with the genre more difficult, both as readers and writers. That challenge remains today, a lot of Arabic science fiction tends to mimic Western models, it hasn’t quite found its own voice yet.

Linguistically, Arabic hasn’t always adapted easily to the demands of science fiction.

And beyond that, there’s a lack of clarity about what science fiction actually is. Some people even clumsily claim ‘One Thousand and One Nights’ is science fiction. I would love to see a great science fiction novel being nominated for Al-ja’iza al-arabiyya one day.

In a world increasingly futuristic by virtue of AI, the realisation of things we used to see in dystopian movies and science fiction are now becoming our reality. Because of this, how does the genre differ and how does it become more important?

Fagih: 30 years ago, science fiction was developing and defining itself, now it's more… factual, real. The big existential and philosophical questions traditionally explored through science fiction are becoming intertwined with our lived reality, particularly in countries like Saudi Arabia. Now, there’s an urgent need to address these questions, and science fiction, with its rich metaphorical potential, is a perfect medium. From the works of Bradbury, Heinlein, and Shelley, science fiction has always served as a lens to explore life’s complexities.

The world grows more uncertain every year. Take 2020, for instance; the pandemic turned everything upside down. It was a vivid illustration of science fiction becoming reality. AI is making the genre more immediate, more tangible, as the line between fiction and reality blurs.

As an art, science fiction has always been a celebration of the unimaginable and the unrealistic. The gap between imagination and reality is becoming narrower. As a result, current science fiction feels more relevant to our world, while the next wave will undoubtedly push the boundaries of imagination even further. This shift means the genre will only become more engaging, electrifying.

A key theme spanning your works is the notion of ‘void’ and the questions that accompany it. In 2025, with the rise of AI and increasing geopolitical uncertainty, the notion of the ‘void’ seems even more urgent. How does science fiction enable you to explore this void, whether historical or futuristic?

If we define the void as feelings of uncertainty related to ourselves and the world around us, then I believe that AI is there to expand that void, it will not fill it. We are befriending and falling in love with mere algorithms. I see my children interacting with AI accounts in a way that is both vivid and unsettling.

In my latest novel ‘The Portrait of the Void’, I use the concept of the zero as a symbol of the void. It represents not only the history of the number zero but also the inner emptiness of someone like Leonardo Fibonacci. I questioned whether he belonged more to the Arab world or to 13th century Italy - was he more connected to Christians or Muslims? I used the void metaphorically to explore his mental state as he grappled with his identity and culture.

As for science fiction in the age of AI, I don’t think it will close the gap or fill the void. If anything, it will only remind us of how disconnected we’ve become due to technology. We may be alive, but we’re not truly living unless we actively think. We don’t engage in deep discussions anymore, we don’t argue, we simply ask AI and accept its answers. If we don’t like the response, we just train it to speak in the style we prefer. What will be the consequence of this? I think we’ll end up with an emotionless generation. This would make for an intriguing character in any fictional plot.

Science fiction allows us to explore this void, this moment in time, and imagine various scenarios, picking and choosing the paths that could unfold. Ultimately, science fiction is the art of speculating about the future, but it’s also about reflecting on the present and the histories that have been forgotten. We need to speculate about what lies ahead. Science fiction serves as a warning, offering us an opportunity to prepare and to stay vigilant.

There’s a common misconception that science fiction is solely restricted to imagining future scenarios. However, your works often explore gaps and voids in history, blending fantasy with scientific elements and imagination. Can you talk a bit about the connection between history, imagination, and sci-fi?

There’s a common misconception that science fiction is solely restricted to imagining future scenarios. However, your works often explore gaps and voids in history, blending fantasy with scientific elements and imagination. Can you talk a bit about the connection between history, imagination, and sci-fi?

Fagih: I write both science fiction and historical fantasy, genres that often intersect and are, in many ways, interdependent. They allow me to engage with history, to record it and explore it from a speculative angle. Both genres serve not only as a form of education but as an invitation to think critically. They offer the opportunity to immerse oneself in a particular time period, whether real or imagined, and ponder what life could have been like at that moment in history.

At the core of my novels is the act of filling gaps, the voids of forgotten histories that were never recorded, marginally addressed or that remain lost to time. What about the events that might have happened but were never written down? The endless possibilities of "What could have been"? As a writer, my role is to sift through these possibilities, follow the threads of these untold stories, and build a human experience around them. Science fiction and historical fiction hinge on speculation, on imagining the "could haves" and the "would bes." Imagination is the key that fills these gaps.

As Arabs, we live in a unique contradiction. We have a profound connection to our past, yet the future is a space of intense focus, especially when it comes to ‘futurism’. We are deeply tied to history, yet we yearn to look forward, with heavily uncertain presents. This tension shapes much of my work.

At the end of the day, history is man-made. It’s a narrative that has been written, shaped, and adopted by someone, often for specific political or ideological reasons. Speculation, whether through science fiction or historical fiction, allows us to dissect the common narrative, to pull it apart and question the dominant narrative voice. It’s about highlighting the overlooked characters, the anti-heroes who have been neglected in favor of the champions. Personally, I find the champions less interesting.

Contrary to the common view that history is a series of scattered, disconnected events, everything is interconnected. This is the foundation of science fiction: exploring the missing links, the things that were never fully understood or recognised. That’s what excites me about the genre, its potential to open doors to new possibilities.

Take my latest novel ‘The Portrait of the Void’, for instance. It revolves around the concept of zero, its philosophical origins and mathematical interpretation. The question of who first discovered zero has always intrigued me. Was it the Indians, the Arabs, or someone else entirely?

It struck me one day that it was Fibonacci who brought it to Europe’s attention. He was a mathematician who became quite established in the later discipline of computer science. I used to give lectures about algorithms attributed to him. Finding out that this man spent time in Northern Africa and learned Arabic assured me that he was responsible almost solely for introducing the notion of the Arabic numeral zero to Europe.

These are the types of "missing links" that fascinate me. I love to explore them, to speculate on the untold stories that could reshape our understanding of history, science, and culture.

Similarly, my previous novel, ‘The Impaler’, was driven by a similar fascination. Everyone knows the myth of Vlad Dracula, but I was intrigued by the fact that he was raised alongside Mohammed the Conqueror, another towering historical figure. The idea that these two arch-enemies once shared a space, that they clashed in such dramatic circumstances, this was another "wow" moment for me.

I’m always searching for these unusual intersections in history, where two extraordinary figures might have crossed paths in unexpected ways. It’s those twists that I’m eager to unravel and explore.

In a society increasingly obsessed with the future and propelling itself towards it at full speed, what is the importance of looking back to the voids in history and filling in silences for the future? How is looking back key to the way we look forward?

Fagih: Before we race ahead, full steam, it’s crucial to realise that we aren’t discovering anything fundamentally new in ourselves; we’re simply echoing the lessons of the past. Our predecessors have likely already tried and done everything.

We need to learn the importance of learning from the past rather than simply inventing. History, speculation, and science fiction are essential in humbling us. Before marching into the future and attempting the unprecedented, we must first look back.

Yes, people didn’t reach the moon before 1969, but let’s not confuse technological advancement which is, by definition, new, with the human experience on this Earth. It’s vital to preserve our humanity and remember, and learn from, our predecessors.

The blunt notion of black and white just doesn’t exist. History is grey all over. It’s science fiction and imagination that help us grapple with this greyness. They make us pause, look back, and reflect before we move ahead at full speed.

Imagination is often perceived as being under threat in the digital age, particularly with AI automating creativity. There’s this growing belief that we no longer need imagination when AI can think for us. How do you see the role of imagination evolving today, and what role do you think AI will play in this shift?

Fagih: Since the genre emerged, sci-fi writers have become the philosophers of the new age. We're pushing the boundaries between imagination and reality. Certain ideas are so unsettling that they almost become unbearable to write about, and confronting the questions they provoke can feel impossible.

Consider the idea of a loved one who has passed away - imagine that their entire consciousness could be digitised and preserved. What happens when we plant AI, when we inject digital imagination into a human brain? Each word in that sentence triggers profound questions about consciousness, thought, and what it means to be alive.

The very notion of life is shifting. Our understanding of consciousness is being redefined. Death, too, seems to be losing its finality, and the concept of humanity itself is dissolving. In this new world, all living creatures, as we know them, may be rendered obsolete. But these new creations, AI, may outlast us, provided their batteries keep running.

Our existence is becoming increasingly digitised. This is why imagination, and by extension, science fiction, are more vital than ever. These genres force us to confront the big questions that technology often tries to suppress. They are essential in restoring consciousness, even as it becomes increasingly muffled.

Imagination and sci-fi provoke difficult questions and continually generate different possible answers. They equip us with the tools to navigate and understand our rapidly changing reality.

As we begin to accept AI's answers without question, there will come a point when our own minds become disabled by this convenience. It’s the role of imagination and science fiction to sound the alarm.

- Previous Article Over Half of Egyptian Households Live in Rural Areas

- Next Article Pilgrims Can Now Activate eSIM Cards Upon Arrival in Saudi Arabia