Syrian Band Jazeera 10 Are Not Trying to Be Anything

The Berlin-based Syrian band reflects on their journey, displacement, and the meaning of being ‘Matloob’.

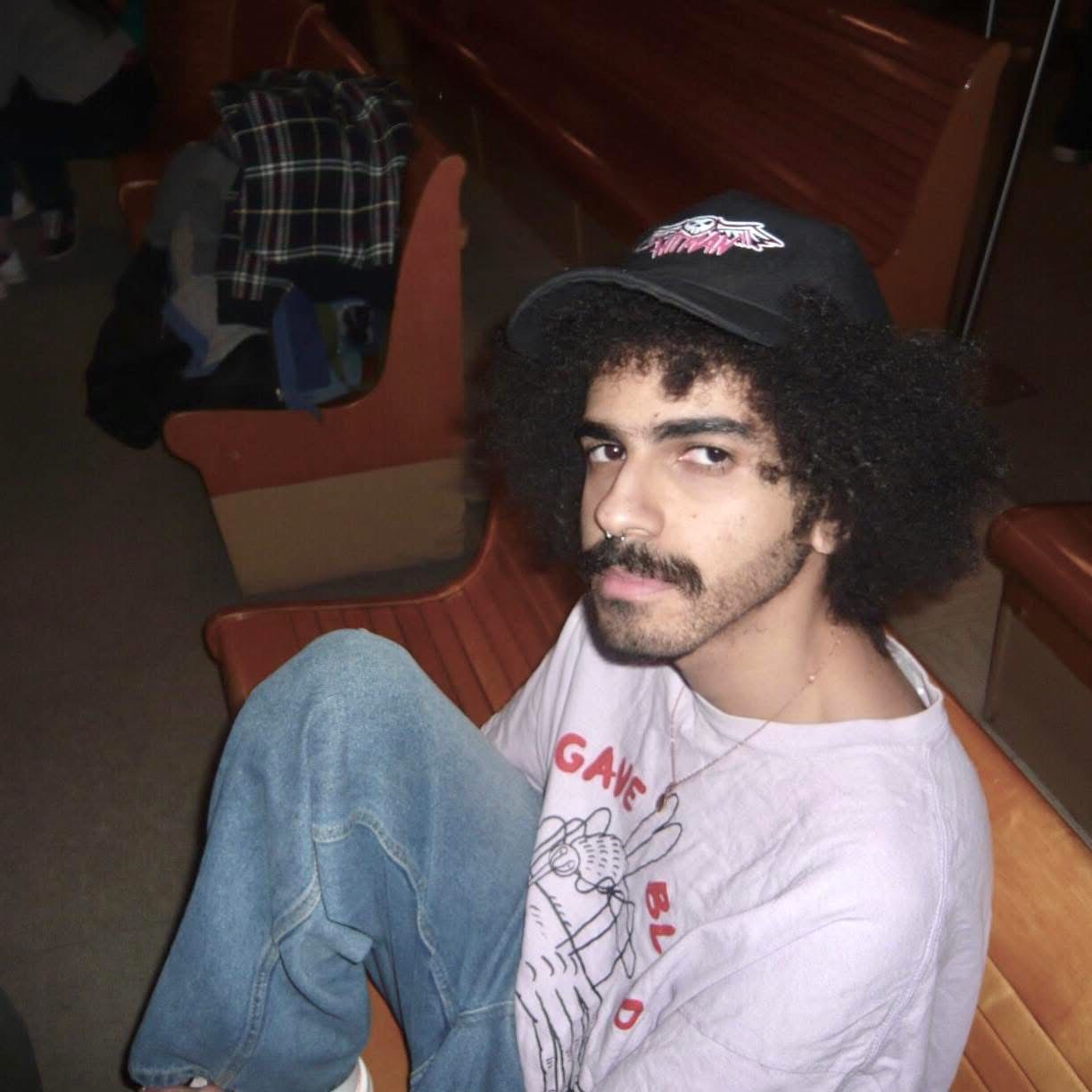

Forty minutes into my conversation with Jazeera 10, Anas Maghrebi exhales a cloud. 'You mentioned the word 'liminal', and funny enough, that was actually one of the first titles I suggested for the band before we decided on Jazeera 10,' says Humam Abo Alraja, who occupies the left side of my screen. He is flanked by a Google Meet backdrop that could pass for the Men In Black headquarters.

On the right side, Louay Kanawati, Muhammad Bazz and Anas share a separate frame. “It must’ve been 2009 when I first met Anas,” Bazz recalls. “He was singing at a concert, and I just knew I had to ask him to join my band. A little while later, the three of us came together in Syria, and we’ve been best friends ever since.” Behind them, their website remained open, with a 3D bronze rendering of Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker sitting at its centre.

Though we'd only exchanged a few words before our chat, the band’s camaraderie made me feel less like an outsider crashing the cool kids' table and more like we were simply continuing a conversation we’d been having for years.

Their latest EP, ‘Leil El Mataleeb’ (‘Night of the Wanted/Fugitives’) revolves around ‘El Matloob’, which is both a name as well as a condition. To be ‘Matloob’ is to be hunted. The group sees this as an inevitable reality of existing in a foreign country. But this state of unease can still haunt you at home too, depending on who you are, what you believe, or how the world has chosen to see you.

“He’s a person constantly on the move, simply because staying put isn’t an option.” The moment you look around and realize your life no longer belongs to you in the way it used to is when you become ‘Matloob.’

What’s the story behind the name Jazeera 10?

Anas: Jazeera 10 is part of the neighborhood where Louay grew up in Damascus. Bazz and I used to hang out there with him all the time. There are several different Jazeeras in Louay's neighbourhood, but Jazeera 10 happens to be ours.

How would you describe your sound to someone hearing you for the first time?

Bazz: It’s a bunch of things, really. We try not to stick to just one sound. It's more about what we like and what comes organically. There are a lot of layers, like synths, guitars and vocals, that come together in a way that’s supposed to feel sort of colourful, but I guess we try to find a balance between shoegaze and dream pop that has a bit of a hazy, atmospheric feel.

Your lyrics often touch on themes of displacement and longing. Given the current changes in the region, including recent developments in Syria, do you ever feel pressure to make your music explicitly political because of where you're from?

Bazz: Of course there’s always this pressure or expectation that as an Arab artist, you have to talk about displacement or be political in some capacity. But it’s not something we actively think about in that way. It just happens. Like for example, when you lived abroad, you didn’t just wake up and decide, ‘Ah I’m going to be political today!’ right? Because that would be silly.

The reality is that existing anywhere, whether that be Montreal or Berlin or wherever and being who you are makes you a political being without even trying. But honestly, we felt some of that even before leaving Syria. It wasn’t just about war or migration. It was there in the little things too, like feeling disconnected from the music our parents listened to and searching for something that felt more like us.

Anas: We’ve always used whatever imagery felt the most natural to us. It’s not like we’re going to reference, I don’t know, the Mississippi River. I know nothing about the Mississippi River but I do know the Al Asi River. So, to answer your question, we write about what we know and the places that have shaped us. If people choose to see something political in that, then it's fine. But we really are just drawing from our own lives. We’re not trying to be anything.

Speaking of Berlin, I couldn’t help but notice ‘12051 Berlin’ on your second EP - there's way more acoustic stuff happening there compared to your other tracks. Given the city’s history as a cultural melting pot, how much does Berlin itself shape your sound and creative process?

Bazz: This is a piece we play with just a ukulele and an acoustic guitar. It’s actually named after a postcode of a neighbourhood we lived in for a while in Berlin. Late at night, Louay would pick up the ukulele, Hikmat would grab the guitar, and when we first heard it, we immediately pictured that place. So in that way, Berlin has definitely seeped into what we do. We’ve always been guys who like things that are a bit softer, sweeter, with maybe a dreamier melody. We started this because we just wanted someone to play a light drum machine, some warm chords to create something that doesn’t sound like it’s trying to fight you. And I guess that’s what we ended up making.

How often do you play live there? I really enjoyed your rooftop performance.

Anas: Honestly? We’ve done, like, two gigs last year. One was at a festival, and after that, we took a break. We were like, let’s work on new material and actually get it right before we go back out there. It’s life or death. You gotta make it sound good, especially when you're working with a sound like ours.

When you listen to Dari El Hal and Leil El Mataleeb now, do they feel like distinct moments in your artistic growth? Dari El Hal seems to reflect a lot about escape and survival, while Leil El Mataleb leans into themes of fire, poison, and struggle. Do you see the latter as a continuation of the former or a shift into a new creative direction?

Anas: We actually made rough drafts of both ‘Dari El Hal’ and ‘Leil El Mataleeb’ at the same time, and when we listened back, they felt like completely different moods, separate energies. That’s how we decided to develop them into two distinct projects. ‘Dari El Hal’ has a certain stillness to it. Even the cover - blue, water. There’s no fire there, no real anger. ‘Leil El Mataleeb’, on the other hand, is the opposite. If anything, ‘Leil El Mataleb’ might be even more personal.

Is there any type of music that you’d say has had the most influence on your work?

Humam: I’d say we’re influenced by everyone from Sigur Rós, early MGMT, M83, and Beach House. We also like George Wassouf and Umm Kulthum.

Louay: Yeah, It’s kind of a little bit of everything to be honest. We focus a lot on the feeling we want to create. A lot of the time, when we're writing, we’re imagining scenes or specific images. This can include art or films too.

That’s interesting. So, what films or filmmakers have influenced this visual side of your music?

Humam: One filmmaker who really stands out is the late David Lynch. We may not realise it when we’re doing it but we definitely draw from that same sense of liminal unease in ‘Twin Peaks’, along with a bit of nostalgia.

What does this EP mean for you personally?

Anas: One of my friends, Odai, used to ask me, 'Why are we fugitives?’ every time we found ourselves tangled up in a mess. He’d say this when referring to our friends and people whose heads were just as knotted as ours. So I asked him, ‘What do you mean by that?”

A chase, he said, is made up of many things - everything in the world is in pursuit: papers, family, love, politics. That’s when we came up with this metaphor, using the word ‘El Matloob’ as the core of this EP.

The album sort of tells El Matloub’s story. In the song ‘Allah Ma'ak’ (‘God is With You’), it starts with him, the very moment of his birth. His mother’s voice, telling him “Allah ma’ak," almost like a guide. And as he grows, those words stay with him: his first steps, his first love, his first heartbreak. The first words he heard, upon entering the world, followed him through the streets of his home, across the distances he crossed through borders, and over the years.

Jazeera 10’s Dar El Hal and Leil El Mataleeb are both available to stream on Spotify, Apple Music and YouTube.

- Previous Article Here’s Where You Can Volunteer This Ramadan

- Next Article Palestinian Film 'No Other Land' Wins Oscar for Best Documentary