'Cleopatra: Her Real Story' - Defying the Netflix Narrative

After filmmaker Curtis Ryan Woodside and Egyptologist Sofia Aziz were tapped to work on Netflix’s Cleopatra documentary, they set out to create their own with help from experts who hailed from Egypt.

"This is Cleopatra, a pharaoh, ruler of Egypt. But who was she really? Too much focus on her sexuality. Too much on her lovers. Not enough about the real Cleopatra." - Curtis Ryan Woodside, filmmaker

"Thousands of years later, we're still talking either about the men in her life or what she looked like, rather than her accomplishments." - Sofia Aziz, biomedical Egyptologist

When filmmaker Curtis Ryan Woodside and Egyptologist Sofia Aziz were tapped to work on the Netflix production of 'Queen Cleopatra' in 2021, they dropped out almost immediately after their historical expertise was overridden by political preoccupations. They set out to produce their own documentary, titled 'Cleopatra: Her Real Story', making sure that each and every second was based on historical evidence.

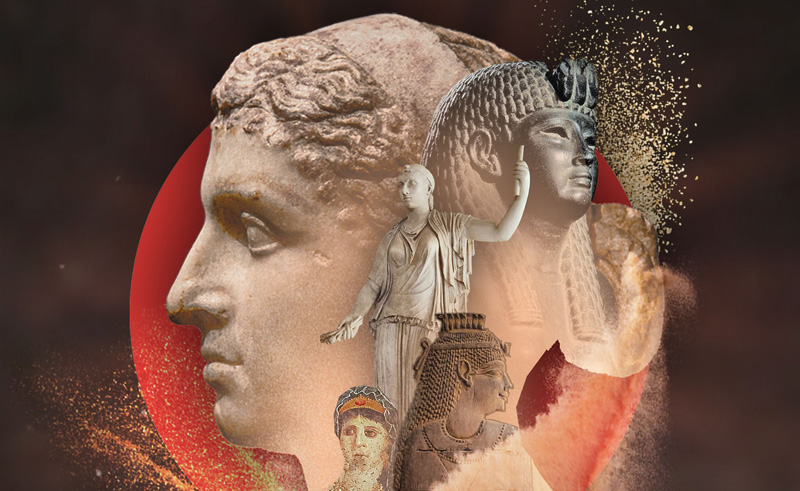

With contributions from trusted Egyptologists and historians who themselves hailed from Egypt, the documentary has been released for free on YouTube to much positive fanfare. This is the story behind ‘Cleopatra: Her Real Story’ and its efforts to honour this powerful figure in Egyptian history, in defiance of the revisionism that has been hoisted onto the public by an American media giant... The fascination with Cleopatra VII's appearance has plagued history for millenia. It began during her lifetime when contemporary Romans demeaned her as "Caesar's Egyptian whore" and it has persisted to the modern day, where arguments over her beauty and womanhood have become replaced by - or perhaps insidiously entangled with - impassioned discussions over her ethnicity. Could Cleopatra have been black, or could she have only been light skinned? Should an Israeli supermodel be cast over an Egyptian or Greek actress because she would be, in some people's eyes, “more beautiful” that way?

The fascination with Cleopatra VII's appearance has plagued history for millenia. It began during her lifetime when contemporary Romans demeaned her as "Caesar's Egyptian whore" and it has persisted to the modern day, where arguments over her beauty and womanhood have become replaced by - or perhaps insidiously entangled with - impassioned discussions over her ethnicity. Could Cleopatra have been black, or could she have only been light skinned? Should an Israeli supermodel be cast over an Egyptian or Greek actress because she would be, in some people's eyes, “more beautiful” that way?

The controversy manifests itself differently with every decade. And little wonder - even before the tomb of Tutankhamun was ever found, Cleopatra VII had been the primary source of Egyptomania all over the world. Every civilisation found itself entranced by the story of the last Pharaoh of ancient Egypt, and her romantic entanglements with two of the most powerful men in the world leading up to her tragic downfall. Whether it's a dozen Hollywood films or a play penned by William Shakespeare, the story has gone through countless iterations - each and every one of which was morphed by that culture's value of beauty and worth, and projected onto Cleopatra herself.

The fierce debate over her appearance has once again been reignited by Netflix's latest docudrama series, 'Queen Cleopatra', in which the Macedonian Greek monarch is played by African-British actress Adele James. Directed by Iranian-born British-American filmmaker Tina Gharavi, 'Queen Cleopatra' is part of the 'African Queens' docuseries by African-American executive producer Jada Pinkett Smith, which had previously covered the life of Njinga, the 17th century queen of Ndongo and Matamba, in its first season.

But what about her? What about the real Cleopatra?

DROPPING OUT OF NETFLIX

After being approached by the production team of the Netflix docudrama in 2021, Curtis Ryan Woodside - a filmmaker and Egyptologist from South Africa who is now based in Italy - had initially relished the opportunity to make a documentary about the life of Cleopatra VII. With a lifelong passion for history and Egyptology, Woodside has produced and released in-depth documentaries for free on YouTube, most of which feature analysis and insights from trusted historians and respected experts in their fields. For him, this was an opportunity to finally tell the real story behind Cleopatra, free from the drama that has clung on to her for thousands of years; an opportunity to disprove myths and legends around her, and to bring about a historical account that recognises her life and accomplishments as a powerful individual.

Woodside immediately dropped out of the Netflix project, however, when the producers made their intentions clear. He submitted his pitch alongside Sofia Aziz, an accomplished biomedical Egyptologist who was also tapped for the project, and the two of them were contacted via video call to discuss what they could offer in the way of facts.

"It was then that Sofia Aziz and I learned that they had a political agenda to change the known identity of Cleopatra," Woodside tells CairoScene. "Thus, neither of us went forward with it. A friend kept me up to date on the production, and I learned there had been many hiccups for the Netflix show. Many crew members were leaving because of disagreements with Jada Pinkett Smith. The show had actually been cancelled because there were so many issues, but then it somehow got picked up again." Woodside and Sofia Aziz became more determined than ever to create their own documentary; one that would tell the true history of Cleopatra, based entirely on what has been revealed through evidence, titled 'Cleopatra: Her Real Story'.

While the exact nature of these behind-the-scenes discussions that led to the Netflix documentary may never be fully revealed, director Tina Gharavi has made her political inclinations no secret. In interviews and on social media, she has been quoted saying, "I realised what a political act it would be to see Cleopatra portrayed by a Black actress" and that her concern was to "find the right performer to bring Cleopatra into the 21st century." (Because a Greek or Egyptian actress would be SO passé in a role mostly taken by actresses who were neither, apparently). Gharavi does not appear concerned with telling a story of history, but of realigning history to address modern - and, frankly, Eurocentric - political concerns.

Based on these comments, the Netflix documentary was not made with a viewpoint that has been fully divorced from Eurocentric biases of white dominance. This viewpoint sees black visibility as necessary to fight back against Eurocentrism - and, in radical cases, has manifested as a reactive form of Afrocentrism as a result. It was not made with a viewpoint true to Egyptians and Greeks that saw race and ethnicity differently, who saw their history as a unique extension of themselves. It does not even acknowledge their concerns that their history is, instead, being treated as a pawn in some Western game of racial politics.

In responding to these concerns, Gharavi fails to consider the Egyptian perspective, instead taking the opportunity to malign, dismiss and mock them. She projects the Eurocentric views with which she is so preoccupied onto them, accusing them of valuing "proximity to whiteness" rather than - perhaps - proximity to Greekness or Egyptianness. She speaks down to “Amir in his bedroom in Cairo” as someone who is ignorant and uneducated, rather than engaging with him as a member of a culture and history she chose to depict. She lectures Egyptians by condescendingly asking them why they would want Cleopatra to be Greek when they themselves are Egyptian. “Why would that be a good thing to you?” Gharavi does not consider that this rhetorical question does have an answer, that this difference in ethnicity is in fact at the heart of Cleopatra’s story, essential to the historical context in which she existed, and the historical context that informs Egypt as it currently is. Gharavi’s film would never even attempt to capture this. The Netflix documentary would always be a Western product for Western audiences, made by a Western media giant to pit one Western agenda against another.

“The Afrocentric movement is trying to take other people’s culture, rather than embracing their own, which is very sad,” Woodside reflects. “I myself am from Africa. I was bullied for having black friends at school. I wear Zulu sandals, not because I'm saying I am Zulu, but rather because it’s part of the culture of my country. The only people who have ever complained about my Zulu sandals are white people. Black people have always been proud that, as a white South African, I can be proud of African things. At the end of the day, the protection of a culture should always come from the place where that culture is being attacked.” AN EGYPTIAN NARRATIVE AS TOLD BY EGYPTIANS

AN EGYPTIAN NARRATIVE AS TOLD BY EGYPTIANS

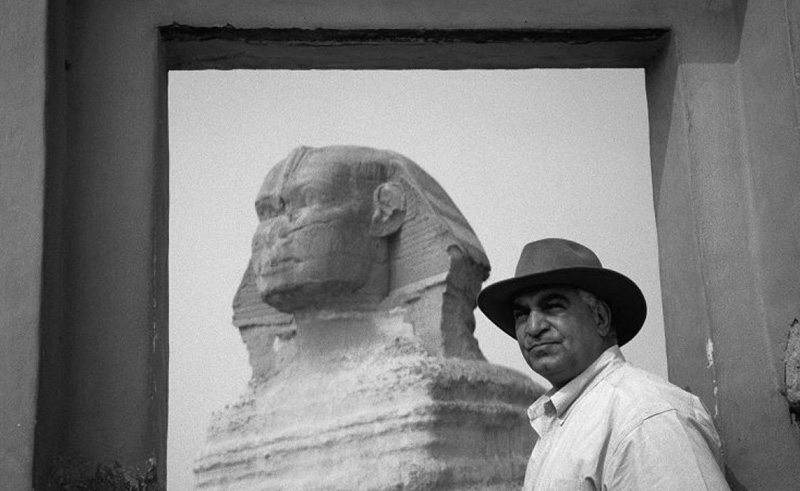

Woodside and Aziz reached out to trusted archaeologists and historians who hailed from Egypt to help with their production, including the likes of Dr. Zahi Hawass, the famed Egyptologist who previously served as the country's Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs. "The same day that the Netflix trailer was released, I was already in contact with Dr. Hawass, to tell the truth," Woodside shares. "All of the experts have been studying Cleopatra for years, and their insights provided so much new information on the ancient queen. I wanted the majority of the story to be told by actual Egyptians. This was important to me!"

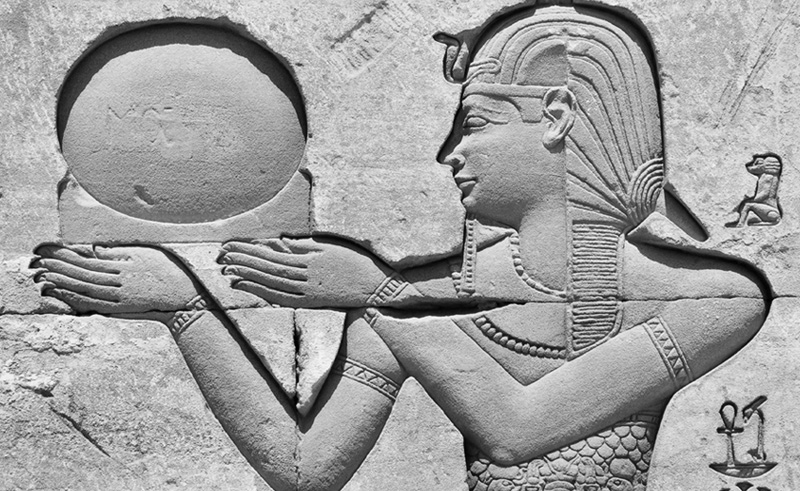

‘Cleopatra: Her Real Story’ begins by indirectly addressing claims made by the Netflix docudrama, in which one scholar confidently proclaims, “I don’t care what they tell you in school, Cleopatra was black.” From the very start of the film, ‘Cleopatra: Her Real Story’ utilises historical sources to determine Cleopatra’s ancestry, birth and ethnicity, bringing up each prominent theory and referencing the evidence on which they are based. The documentary walks us through Alexander the Great’s liberation of Egypt from the Persian Empire, and the establishment of the Ptolemaic Dynasty after one of Alexander’s generals settled down and assumed rule of Egypt.

We are then guided through the dynasty’s complex family tree, which is fraught with inbreeding and special rules about who may ascend to the throne - rules which strictly exclude children who have been born out of wedlock. Although Cleopatra’s mother has never been explicitly spelled out, the evidence is laid out that allows you to determine for yourself who may have been the most likely candidate. Would it have been an unknown rumoured priestess of Ptah whose child would likely have never been allowed to rule without loud and boldly recorded objections by Cleopatra’s detractors, despite what the Netflix documentary might claim? Or would it have been Cleopatra V, the legitimate wife who was noted to have died during childbirth around 69 BC, the same year when Cleopatra VII was born?

Amongst the evidence for Cleopatra’s appearance were statues, murals and coins commissioned by Cleopatra herself, which consistently depict her with features that were typical of light-skinned Macedonian Greek women, and shared a lot in common with the light-skinned Egyptian women who had lived as her contemporaries during the Ptolemaic and Roman eras. As a 2017 genetic study of the Fayoum mummies by Schuenemann et al. has found, at least some native Egyptians around Cleopatra's time were indeed light-skinned, despite the belief that these Fayoum mummies were ‘white foreigners’ based on their portraits; their ethnicity put into question based on the presumption that ancient Egyptians must all collectively be dark-skinned, and that light-skinned Egyptians are a recent product of “Arab invaders'' (as Gharavi puts it), and very little else. The physical renditions that once populated her palaces and temples were how Cleopatra chose to depict herself, with full confidence and pride in herself and her right to rule.

In a sense, by denying that this is how Cleopatra looked, one would not just be silencing historians and critics, or racists and internet trolls, or even poor stupid Amir in his bedroom in Cairo - one would be silencing Cleopatra herself.

“Cleopatra Vll is one of those intriguing historical figures that stirs emotions worldwide. She did not have the chance to write her own memoirs. That vacuum has been filled with numerous versions of Queen Cleopatra. She was considered an ‘enemy of Rome’, hence those writing about her either despised her, or had biases that shaped their narrative,” Sofia Aziz explains. “Eradicating these biases is fraught with difficulties. Even in the modern era, Cleopatra continues to be depicted as a seductive temptress, despite only having had two recorded love entanglements throughout her life. I co-produced this documentary to reveal that Cleopatra was so much more than appearances and the men in her life. Ultimately, even Cleopatra’s detractors could not deny that she was an educated, intelligent woman with a magnetic charm, and it was these aspects of Queen Cleopatra that I felt compelled to portray.”

Throughout the film, we follow the course of Cleopatra's life. We learn about her impressive education where she learned several languages, including the language of the native Egyptians, something that the rest of her family had deliberately neglected for generations. Most members of the Ptolemaic Dynasty kept themselves separate from the subjects they ruled over, both genetically and culturally. Not Cleopatra. She learned the language of the Egyptians, immersed herself in the faith of the Egyptians, and - in an unprecedented move - conducted rituals with full respect for the perspective of the Egyptians (even going so far as to dress as a male Pharaoh when appropriate). Cleopatra was surely aware of the gap between her, a Macedonian Greek, and the Egyptians she ruled over. Instead of continuing to dismiss them and impose a foreign stature over them, she chose to engage with Egyptian culture - and, eventually, attempt to re-establish Egypt as an independent kingdom.

Which isn't to say that Cleopatra was necessarily a flawless and benevolent heroine. She certainly had her fair share of brutality, at one point even using condemned criminals as test subjects for a variety of deadly poisons. The documentary depicts all of her actions in a generally non-judgemental light, neither glorifying nor demonising her, but noting her actions within the historical context in which they took place. The film spells out her legacy from her birth to her controversial end, even discussing in great detail the possible theories behind her alleged suicide, and what the available medical records suggest as the most likely methods of death.

Just as important as the documentary’s measured, fact-based stance was the respect with which the sources were treated. It is ironic that the director of the Netflix documentary would so readily dismiss the perspectives of Egyptian critics, when the subject of her documentary - Cleopatra herself - had done so much to win the respect of the people of Egypt. And it is perhaps only appropriate that the producers behind 'Cleopatra: Her Real Story' have, by contrast, reached out to Egyptians in order to give them a platform to speak about the history of their own country, their own past, their own narrative. To tell the story of a Macedonian Greek queen who was entitled to rule as she pleased, and instead chose to be Egyptian - if not in terms of ethnicity then in terms of culture, in terms that were defined by the Egyptians themselves.

HISTORY IS WRITTEN BY THE…?

HISTORY IS WRITTEN BY THE…?

With that in mind, the feedback that 'Cleopatra: Her Real Story' received from Egyptian viewers speaks volumes.

"We have received such positive feedback from all around the world, but mostly from Egyptians, thanking us for protecting their history, and thanking us for having Egyptians telling their history to the world," Woodside says. "What I have noticed is that many of the black people commenting on our film are against Afrocentrism. They are angered by the changing of Egyptian history just as much as the Egyptian public are, and are asking for stories of their OWN great cultures to be told."

As of the time of writing, Netflix's 'Queen Cleopatra' has been given a 2% rating by the audience based on 5,000 reviews on Rotten Tomatoes, with a steadily lowering aggregated score of 10% by professional critics. Woodside and Aziz's 'Cleopatra: Her Real Story', meanwhile, has over 183,000 views with more than 13,000 likes and 145 dislikes, and a positive rating of 98.8% on YouTube. As far as negative feedback is concerned, Woodside says he has only seen about 10 negative comments out of the 2,000 he received. He also notes that he and Sofia Aziz were blocked on Instagram by Jada Pinkett Smith, despite never having interacted with her.

"As I state at the end of the film, 'Whenever I make a documentary on Egypt, I make sure that my friends in Egypt are happy with it, because that is the most important thing when telling their country’s history'," Woodside says. "I will always be on the side of Egyptians when it comes to their history."

Woodside has 25 documentaries on ancient Egypt in the works, with plans to release a docu-feature on Amenirdis I, a Black princess who ruled as high priestess during the 25th Dynasty of Egypt, when the Kingdom of Kush (a powerful Black nation in what is now modern-day Sudan) had taken over the country. After all, Cleopatra was not the only female ruler of Egypt, nor does she serve as a stand-in for every female ruler the country has had - to say that she was not Black does not mean Egypt had no Black female rulers at all.

The idea that Cleopatra was more significant than other Egyptian rulers is in itself a Eurocentric viewpoint, one that sees Egyptian history as defined by its relationship with Greece and Rome, and holds little regard for similar ties to Black nations. When one latches on to her and asks, “Why can’t this powerful queen be Black, when she is so important?”, they implicitly accept that Eurocentric premise as an unquestionable fact, even if it is towards Afrocentric ends. By placing Cleopatra on a pedestal, they prop up a perspective that has ignored Black queens, princesses and priestesses of Egypt for centuries. They contribute to the mythologising of Cleopatra VII, a mythology born of Eurocentrism and rooted in Rome’s sexually-charged disdain for “Caesar’s Egyptian whore”, and continue to bury her true story further.

At the end of the day, Cleopatra can only be what she ever was - neither a symbol nor a substitute, but an empowered individual with a unique and immutable place in Egypt’s history.

- Previous Article Italian-Palestinian Duo No Input Debuts Eponymous Electro EP

- Next Article Egyptian Embassies Around the World

Trending This Week

-

Jan 31, 2026

-

Jan 29, 2026