Cairo’s Historic Gates: The Stories Behind the City’s Fortified Walls

The gates of Cairo reflect the city’s history—marking its defences, migrations and evolving identity.

Since its founding in 969 AD by the Fatimid Caliphate, Cairo has been a city shaped as much by its walls and gates as by the people who passed through them. These gates weren’t just military defences—they were geographic markers, cultural thresholds, and neighbourhood anchors, each with a name that still echoes across the city today.

Like many ancient capitals, Cairo was once enclosed by fortified walls with monumental gates that served both defensive and ceremonial purposes. Among the most significant surviving gates are Bab al-Nasr and Bab al-Futuh to the north, and Bab Zuweila to the south. These were part of the Fatimid city walls rebuilt in the 11th century by vizier Badr al-Jamali. Other gates, now lost or lesser-known, included Bab al-Barqiyya and Bab al-Qantara to the east, and Bab al-Saada and Bab al-Faraj to the west, though historical sources vary on their exact locations and functions.

While some have disappeared, others remain standing—quietly reminding us of Cairo’s evolution from a walled settlement to a sprawling metropolis.

Bab al-Nasr, located in Al-Gamaliya, was first built by Fatimid general Jawhar al-Siqilli and rebuilt by Vizier Badr al-Jamali in the 11th century. Though later renamed Bab al-Izz, the name Bab al-Nasr—‘Gate of Victory’—persisted, as returning armies would pass triumphantly beneath its arches.

To the south stands Bab Zuweila, one of Cairo’s most iconic landmarks, built in 1092. Known for its twin towers once used for surveillance, the gate takes its name from the Zuweila tribe who lived nearby. It remains one of the few surviving Fatimid-era gates and served both strategic and ceremonial purposes for centuries.

In Al Banhawi, located in the historic district of Al-Gamaliya, you’ll find one of Cairo’s oldest and most renowned fortifications—Bab al-Futuh. Established in 969 by the Fatimid general Jawhar al-Siqilli under the rule of Caliph al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah, the gate was initially named Bab al-Iqbal. It was later rebuilt in stone by Badr al-Jamali, who renamed it Bab al-Futuh - Gate of Conquest - following Cairo’s expansion. The gate is known for its rounded towers and defensive design, with Byzantine influences evident in its architectural details.

Cairo’s fascination with gates extended beyond their function. In time, entire neighbourhoods were named after them, embedding their legacy into the city’s geography. Bab al-Shar'iya, built to the west of the Egyptian Gulf by Salah Ad-Din Al-Ayyubi in 1170 AD, was named after the Berber tribe Bano Shairiya. Though the gate collapsed in 1884, the district retains its name and identity.

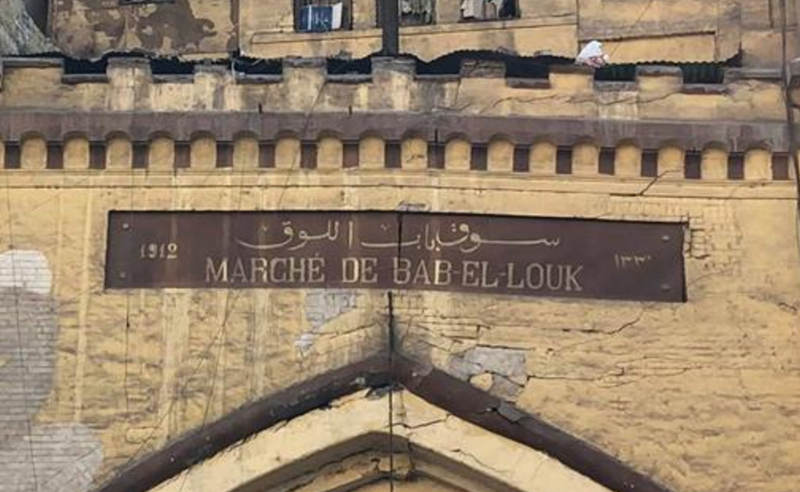

Then there’s Bab al-Louq, a neighbourhood with no visible gate. Once an agricultural area with soft flood-fed soil, it was transformed in the 13th century under Al-Zahir Baybars, who built houses for incoming Mongols, and was later developed into an urban district by Khedive Ismail in 1858, laying the foundations for the neighbourhood that still thrives today. The name endures—“Louq” meaning ‘meadow’—offering a different kind of entryway, one shaped by land use and memory rather than stone.

Cairo’s gates are not relics of the past; they are reminders of how the city has constantly reshaped itself. Some names outlived the structures they marked. Others, like Bab Zuweila and Bab al-Futuh, continue to anchor their surroundings. While the city has grown far beyond its original walls, its gates still mark the meeting points between history and the present. They ask us not just where we are going, but where we have come from—and who we’ve become along the way.