Who is Michael Safwat & Why Did he Switch from Surgeon to Sketcher?

Once a surgeon, now an urban sketcher of disappearing Cairo, Michael Safwat draws, teaches and remembers what developers would rather demolish.

Originally Published on Apr 18, 2025

In the sterile maddening hush of an operating theatre, there is little room for doubt, whimsy, or detours. Precision reigns. That was the world Michael Safwat inhabited for much of his life: one of scalpels, sutures, and systems. As a surgeon, Safwat had grown accustomed to structure, to the rhythmic choreography of medicine, and to the illusion, at least, that things could be fixed, made whole, with a steady hand and a clear plan. But systems, as he would later discover, have their limits.

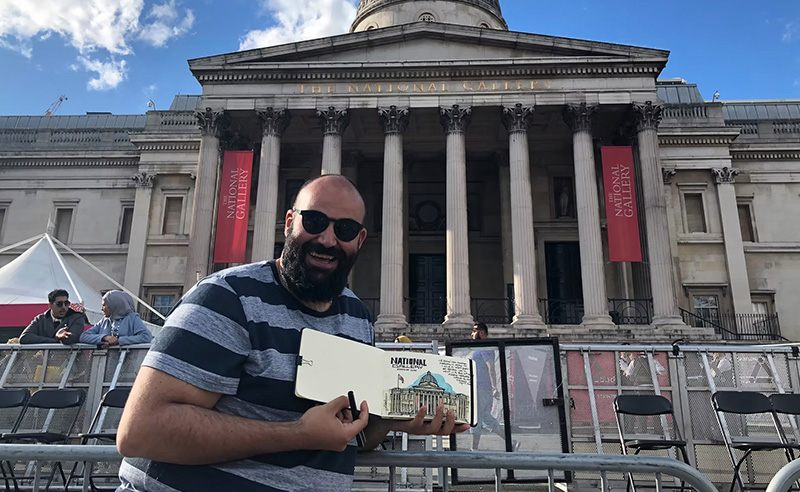

A brush of misfortune, an accident that left him unable to continue his medical career, thrust Safwat into a liminal space: somewhere between structure and chaos, utility and art. It is here, in the seeming wasteland of the post-career identity crisis, that Safwat stumbled upon a new kind of scalpel, one that would not stitch skin but rather slice through layers of history, memory, and urbanity. It happened, fittingly, in Trafalgar Square.

A Sketchbook in Trafalgar Square

There, in the crisp London air—on what was meant to be a brief stop in a longer journey—Safwat observed a curious gathering: people standing around sketching, heads tilted at odd angles like amateur geographers trying to map the soul of a city through its angles and shadows. Intrigued, he approached. They were urban sketchers, they told him, chroniclers of lived space, wielding pens and watercolours instead of DSLRs or drones. “They explained the rules, or lack thereof,” Safwat tells SceneTraveller. You don’t need anything fancy, just a sketchbook and a pen. Naturally, Safwat, whose pragmatism had long been his compass, did the opposite, “I went out and bought all the wrong supplies, spending a small fortune on tools that I’ve never used, even to this day.”

But something had been set in motion. He began sketching in earnest. First as a traveller, then as something more.

From Europe to the Corner Kiosk

COVID-19, the most effective of immobilisers, forced him to remain in Egypt and reckon with proximity. Like many middle-class Egyptians of his generation, he confesses to suffering from a mild yet persistent “‘O’det Khawaga”, an inferiority complex that elevates anything foreign, especially Western, as automatically more refined, more worthy of attention. When he first began sketching, he gravitated toward European landmarks and global urban icons, believing, almost involuntarily, that his own city was somehow too messy, too familiar to be art. Yet, when the pandemic hit, and Michael’s furthest journey became the kiosk down the street, everything changed.

Seeing Cairo for the First Time

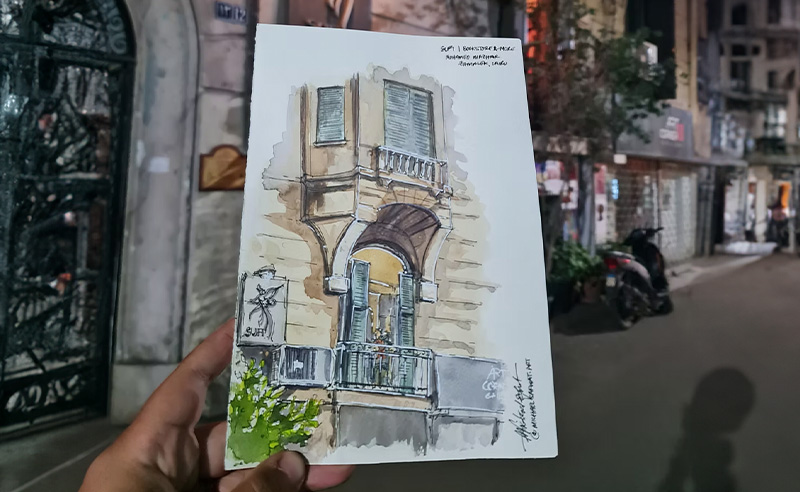

The travel sketchbook, once filled with landscapes and boulevards from elsewhere, became a portal to the overlooked, the decaying, and the charmingly mundane corners of his own city of Cairo. He began in the area of Daher, sketching a street he had likely passed hundreds of times before but never truly seen, “This, perhaps, is the essential act of the urban sketcher: to unsee what routine has blinded you to, and then see again, with all the tenderness that act implies.”

Cairo, he discovered, is a museum, a manuscript written, erased, and rewritten over millennia. Its minarets carry the echoes of churches, which in turn were built on the bones of temples. There is, as Safwat likes to point out, “a civilisational sediment here”; “a mosque on the back of a synagogue on the back of a fortress.” He began sketching these layers, not as isolated architectural objects but as storied bodies, with breathing people.

As Safwat’s practice morphed from travel sketching to urban storytelling, it was no longer enough to draw a building. He needed to know what it had been, what it had witnessed. He became obsessed with origin stories, not just the architectural lineage of a place, but its socio-political genealogy. Why here? Why this way? What forces, human and otherwise, made this structure what it is today? Art became, for Safwat, a kind of exegesis. Each drawing a textual analysis, each façade a thesis.

In October 2021, he launched ‘7akawy Antika,’ a series of daily sketches published over 15 days, chronicling Cairo’s vanishing landmarks. It was part elegy, part act of resurrection. His drawings came with anecdotes, historical tidbits, and commentary, a visual zine zigzagging across a city of ghosts. There was humour too, and irony. Who knew urban decay could be so intimate?

Workshops, Watercolours, and New Geographies

Soon, Safwat’s oeuvre expanded. He launched workshops, not for the art-world initiated but for beginners, for those who believed they could not draw. The premise was disarmingly simple: start where you are. Use what you have. Draw what you see.

And though Cairo remains his muse, Michael Safwat has found a second rhythm in the UAE, where he leads travel sketching and watercolor workshops for a growing circle of urban observers. In Dubai, a city better known for glass than grain, he teaches the art of paying attention, guiding participants through the act of documenting a place with pen, ink.

The narrative widened. Safwat became increasingly interested in expressive watercolouring, having previously lived in the monochromatic world of black ink and clinical lines, “I began teaching students how to channel different moods through colour palettes, encouraging them to discover their own signatures.” Safwat tells SceneTraveller. The act of sketching ceased to be about documentation alone; it became therapeutic, expressive, and deeply personal.

Journeys Measured in Ink

And yet, a type of restlessness persisted. At times, he grew bored—of his own solitude, of repeating the same lessons, of sketching without new questions. He sought out more conversations, more collaborators. In the 385 campaign, he collaborated with calligraphers, merging text and image in intricate, reverent compositions that honoured Egypt’s architectural heritage, one that no one knows anything of. “On the five-pound note, there is a mosque called Abo Hariba, we were never taught that.”

There’s a deep, almost devotional thread that runs through Safwat’s work. A commitment to place, not as a static backdrop but as a protagonist. His Dubai is not the loud, bustling cliché of tourist brochures. It is quieter, more wounded, more strange. His Cairo is full of places you might miss if you weren’t looking, and histories you’d never hear unless you asked.

His work hints at a subtle argument: that the true story of a place, any place a traveller might pass through, is not in its grand monuments but in its overlooked corners; not in the curated museum but in the texture of peeling paint, the ironwork of a neglected balcony, the graffiti half-erased by sun and time. He sketches these things not to preserve them in amber, but to give them one last moment of clarity before they fade.

Trending This Week

-

Feb 23, 2026