Handala: How Naji Al-Ali's Cartoon Embodied Palestinian Resistance

This is the story of a displaced child robbed of the right to grow up.

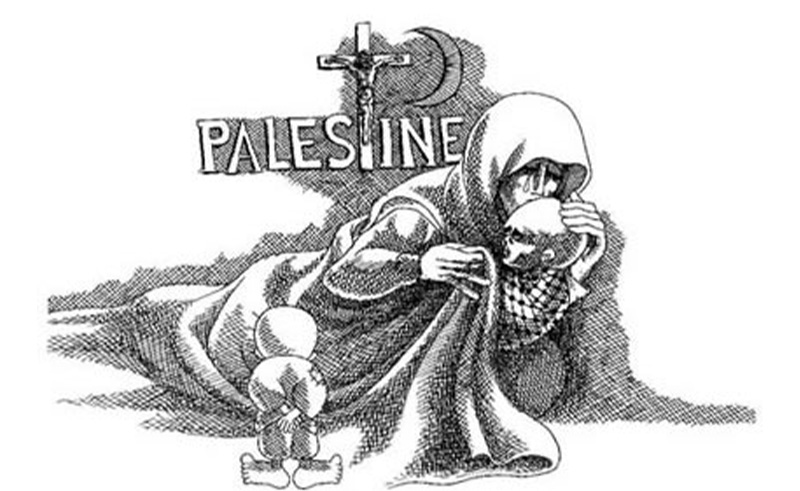

Palestinian political cartoonist Naji Al-Ali’s cartoons, centred around a barefoot 10-year-old Palestinian child in rags named Handhala, represented one of the most powerful and influential forms of storytelling of the 1948 Nakba. Since then, little Handhala has been relaying and preserving the firsthand experience of the onset of the Israeli occupation over 40,000 cartoons, many of which can be found online at handala.org.

The Handhala cartoons chronicle life as a Palestinian refugee, as experienced by Naji Al-Ali himself. Having been forced to flee his homeland alongside his family at only 10 years old, and witnessing the horrors of the Nakba in the meantime, the cartoonist took to Handhala to narrate the man made horrors imposed by Israel. His cartoons reflected numerous themes within the occupation, including the Zionist movement, the experience of refugees and women, UN resolutions, Arab regimes, resistance, and self-portraits.

Handhala first appeared in 1969 in ‘Al Seyassah’, a Kuwaiti newspaper, facing the viewer. The character’s face remained hidden from 1973 onwards, however, due to Al-Ali’s disappointment at the normalisation of Israel by the Arab world and the USA. Since then, Handhala has had his back turned to us.

Named after the handhal fruit, a bitter fruit that grows in the dry areas of the region, Handhala represents the bitter pain and sorrow of forced displacement. However, similar to Palestinian heritage, handhal roots run very deep and are notoriously difficult to erase. The character remains a 10-year-old boy for the same reason that Naji felt like he remained a 10-year-old boy; because he felt he could only continue his life when he would return to his homeland.

In 1987, Naji Al-Ali was assassinated in London. An unknown shooter advanced on him upon leaving his office on July 22nd and shot him in the face. His wish to be buried in Ain al-Hilweh, the refugee camp he had fled to, beside his father could unfortunately not be fulfilled.

“This character was born to survive. I will continue with him, even after I die.”

To this day, Handhala lives on in murals, art, and at demonstrations around the globe.

- Previous Article Italian-Palestinian Duo No Input Debuts Eponymous Electro EP

- Next Article Egyptian Embassies Around the World

Trending This Week

-

Jan 31, 2026

-

Feb 03, 2026