A conversation across borders: architect and historian Mohamed El Shahed reflects on Cairo's shifting narratives and ambiguous identity.

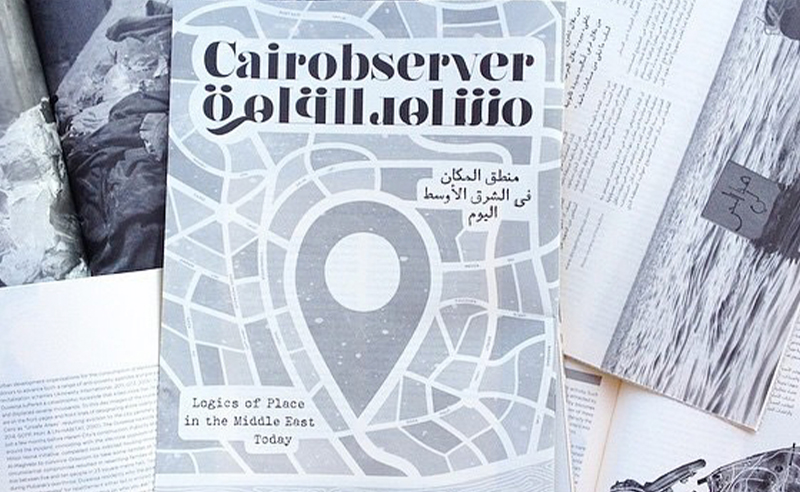

Forced to live far from home, yet always tethered to the heart of his city, Mohamed El Shahed embodies Cairo in every thought and word. The city that once celebrated his vision - a muse that sparked his creativity, lit his soul, and shaped the foundation of his work. An architect by training, a historian by nature, and a storyteller at his core, El Shahed has forever reshaped the Cairene narrative. In 2010, he founded Cairo Observer, a humble blog that evolved into a dynamic archive of the city’s charm, contradictions and ongoing transformation.

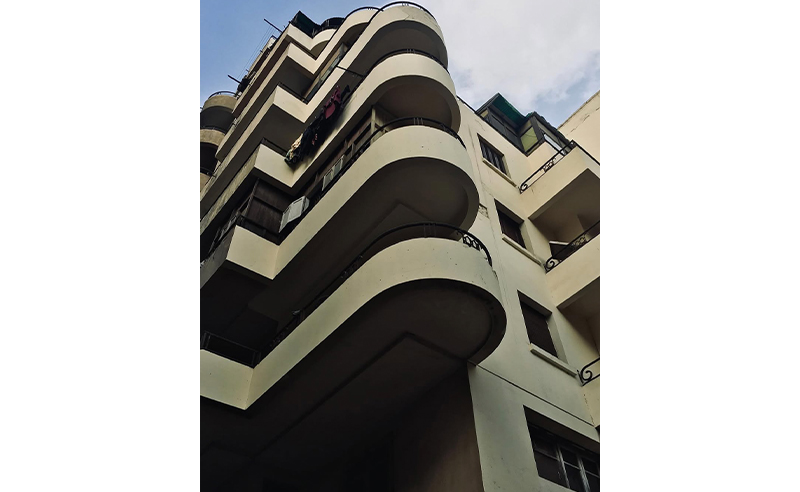

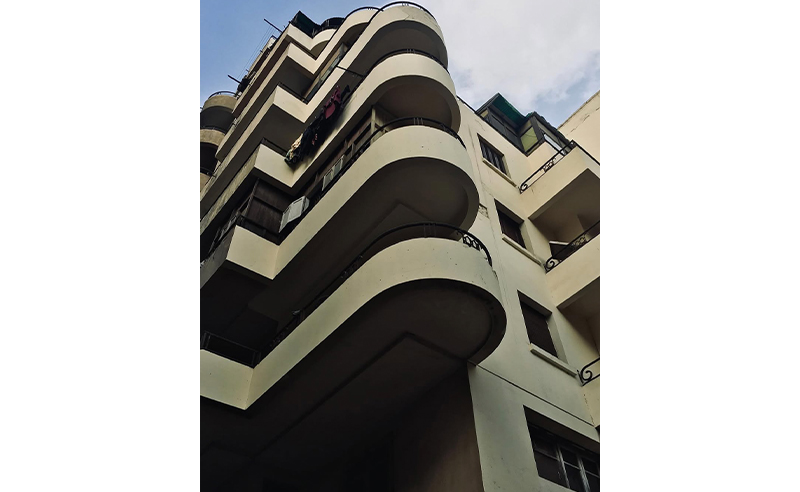

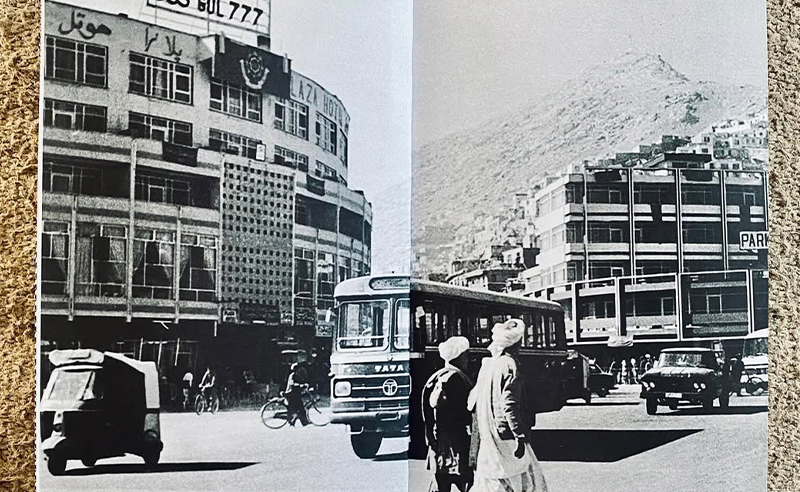

Mohamed El Shahed’s impact reaches far beyond documentation. His book ‘Cairo Since 1900’, developed during his PhD at New York University, maps the city’s ‘Modern’ architectural legacy. Meanwhile, ‘A Revolutionary Modernism? Architecture and the Politics of Transition in Egypt 1936-1967’ explored the profound links between politics and design, earning a dual accolade from Egypt’s Ministry of Culture: one for the work itself in 2021 and another for its translator, Amir Zaky, in 2022.

Yet, it is not the city that owes him a debt; it is all those who now perceive Cairo through his intersectional lens. Scrolling through his Cairo Observer Instagram page, decades after its inception, one is met with a cultural mosaic - an ever-flowing ocean of stories, fragments of Cairo and Mexico intertwining with snippets from across the globe. Each post becomes a piece of a larger puzzle, revealing deeper insights into our history and culture, while shaping how we understand and navigate the present.

In this CairoScene interview, we delve into an ever-branching conversation about the city’s identity, the foggy nature of our cultural memory and the downfalls of nostalgia. El Shahed offers a unique perspective shaped by years of observation, both from within and from afar…

What inspired you to start Cairo Observer, and how did it evolve over time?

Cairo Observer began almost by accident in 2010, when I returned to Cairo after spending 15 years abroad. My fascination with the city led me to create a simple blog as a personal space for reflection and sharing my thoughts. At the time, there were few documented sources about Cairo, and the blog quickly gained readers. Over time, the name of the blog and my own name became almost synonymous. The whole project grew organically, driven solely by my desire to collaborate with designers I admired and create something genuine. The goal was never entrepreneurial, but rather a space for self expression.

Cairo Observer has always felt like an experiment in that way. Looking at my audience today, 31% are from Cairo, while the rest are spread across the globe - London, New York and beyond. The global fascination with Cairo never ceases to amaze me. It’s a reminder of how far-reaching and enduring the city’s allure truly is.

It’s never really about who you’re speaking to. If you’re passionate about something, you write about it because you love it, and then you observe who it resonates with. For me, it’s always fascinating to see who engages with my content - like when a 60-year-old woman from New York reaches out. That kind of connection is endlessly interesting.

Nostalgia is often a lens through which we view the past. How do you navigate the line between romanticizing and critically examining?

I think nostalgia is often born from a lack of understanding - looking at the past without truly knowing it. It's history minus the context, a reductive view that strips away crucial information. We become nostalgic for something precisely because we don’t know enough about it, and in doing so, we tend to glorify the most surface-level aspects - usually aesthetics.

Starting with aesthetics is a shallow approach if you're truly seeking to understand history. Focusing only on the surface is like looking at a cake and only tasting the cream on top. There’s so much more beneath that, the real story lies in the layers, and that's what fascinates me. I want to dig deeper, to explore everything beneath the surface.

Your work remains rooted in an urgency to preserve cultural memory, how do you perceive the relationship between memory and architecture in shaping our collective understanding of Egypt’s modern identity?

Cultural memory requires effort - actively engaging with our past, understanding its layers, and seeking deeper meanings. For me, cultivating a keen, observant eye is the first step toward piecing together the broader picture of what constitutes cultural memory.

One of the biggest issues we face today is the belief that our 7,000-year-old cultural heritage diminishes the value of anything just 50 years old. This mindset is a critical mistake because it overlooks the cultural value embedded in our more recent past. We find ourselves in a relentless race to salvage what we can from erasure, driven by a dangerously narrow definition of culture.

In our context, sometimes simply telling a story becomes controversial, even when it’s just meant to be informative. It’s not about resistance, but about enlightenment. The fact that we perceive it as resistance is telling - it reflects the state of affairs we live in. It’s an indication of how sensitive and charged our environment has become, where even the most straightforward narrative can spark a reaction.

We are living in a time of ambiguity - uncertain of our identity as a society and our connection to history. Yet, despite this uncertainty, we continue to create in the present, whether through music, architecture, or cinema. It’s like cooking blindfolded, trying to figure out the ingredients by touch - thinking, "this feels like dough" or "this seems like a tomato." When the blindfold comes off, what we’ve created is often an unrecognizable mess - like a pizza gone wrong. So even with the best ingredients we can still end up with a bad dish, or a terrible building.

Do you think modern Egypt is more defined by what has been lost or what has endured?

Modern Egypt often feels like a reflection of both what’s been lost and what’s somehow managed to survive. I think of time like a braid - three strands, past, present and future, constantly intertwined. It's how I see Cairo today: a mosaic of fragments, of memories, some faded, others stubbornly enduring.

But the real challenge? How do we connect the past to the present? How do we create something that speaks to all of us when there’s so little context, so little narrative, to tie it all together? Take the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir, for instance. It’s filled with thousands of statues, relics, but without a frame of reference, they remain just objects. When the continuous chain of transmitting knowledge about what something is and what it means is broken, we lose its context. Those relics, important as they are, risk becoming just distant curiosities rather than living history.

Egypt today isn’t just about what’s been lost; it’s about how we preserve, reconnect with, and make sense of what’s still here. I can’t help but think of the Azbakeya Garden, once a vibrant space that linked the old and new parts of the city, brimming with cultural life. Now, it’s another fragment of a past that we still remember, but haven’t yet managed to bring back to life.

How has your physical distance shaped your relationship with the country?

Being away from Cairo feels like being in a long-distance relationship with a lover you can never quite share a bed with. I can’t lie beside her, but I dream of her every night. Even from afar, I feel her presence, and I’m endlessly inspired by her. It is a form of loss, one that’s hard to explain. It’s not exile in the traditional sense, but it’s a kind of removal.

Yet, this distance, whether in time or space, offers a peculiar clarity. From afar, I find myself uncovering new facets of Cairo, rediscovering the city I once took for granted. It’s not the same, of course, I can no longer experience Cairo firsthand. But the internet, one of many windows into its past, has become a place where I gather fragments and slowly piece together an ever-evolving puzzle.

My daily life in Mexico consistently mirrors Cairo in ways I never anticipated. There are echoes of the city in the rhythm of life here, in the culture, the atmosphere, and even in the smallest moments that stir distant memories. It’s a bittersweet feeling, though. Having spent much of my life in exile, I once believed that returning to Cairo would mark the end of my journey - a permanent homecoming. But life, as it often does, had other plans, and I was called to leave once more.

You’ve talked about feeling confined by the structure of academia, yet Cairo Observer offers a more informal space for sharing ideas. What do you think education should look like in today’s world?

I see myself as a naturally curious person, always seeking to understand and engage with the world around me. When I share my perspective, it's not simply to voice my thoughts. I am driven by a deeper purpose rooted in both curiosity and generosity. Learning isn’t just about absorbing information, it’s about reflecting, sharing, and creating meaningful conversations. I take what I discover, transform it, and offer it to others in a way that sparks deeper understanding and connection.

Today, however, many of us consume knowledge passively, absorbing cultural content without engaging deeply with it. This passive consumption is a byproduct of a capitalist society that centers capital, not humanity. Education, in this sense, has become commodified.

However, education doesn’t have to be confined to traditional institutions. True learning is personal and shaped by experience. Travelling, engaging with different cultures, and actively participating in the world teaches you more than any classroom could, especially in the cultural realm.

What's the most rewarding piece of feedback you've received about Cairo Observer so far?

The best feedback I’ve received about Cairo Observer is that it offers an intersectional perspective, a view that cuts across multiple disciplines and ideas. That’s the essence of what I aim to provide. In an age of hyper-specialization, where everything is compartmentalized and siloed, I see this approach as a necessary counterbalance.

Yes, hyper-specialization might have its merits, but it often blinds us to the bigger picture. By exploring the overlaps, I’m trying to piece together a more holistic narrative. It’s about seeing connections where others see boundaries, and I think that’s what makes the platform resonate with such a wide range of people.

You've referenced Egyptian cinema as a tool for understanding architectural and cultural shifts. How do you see cinema, especially in your current work, capturing the essence of Egypt’s evolving urban and social fabric?

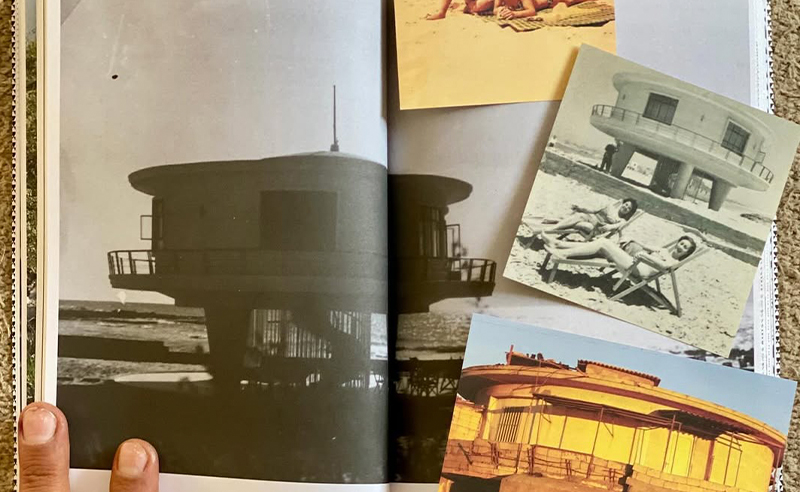

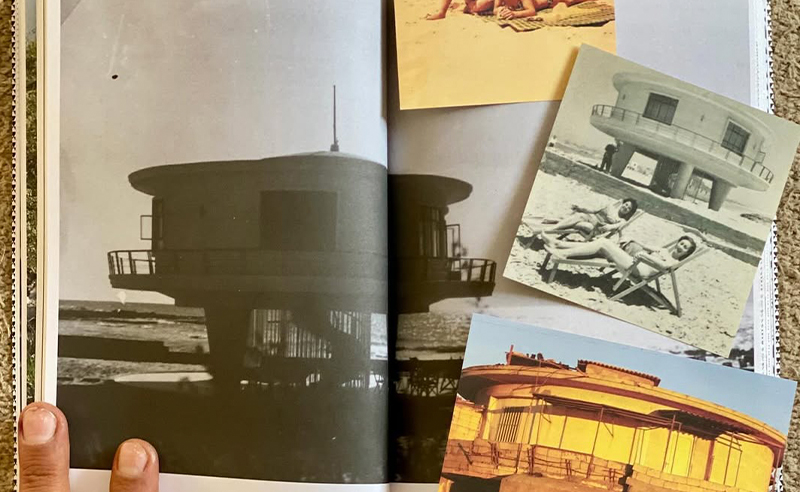

In the absence of archival documents, cinema became a powerful tool for me. I’ve relied on accessible films and even magazines to broaden my perspective. But diving into these sources requires careful navigation. Swimming through the material, reading between the lines, and uncovering the factual insights that often lie beneath the surface.

The older I got, the more I realised that a fundamental part of my education came from watching Egyptian films from the '80s and '90s, not my expensive Western education. It is not just the movies themselves, but the interviews with intellectuals and the cultural discussions. My interest in cinema is completely parallel to my interest in architecture. Both are retainers, expressions of politics, culture and the economy. I don’t care about aesthetics, whether in architecture or cinema, but for me, it’s about experiencing it and understanding where it comes from.

Egyptian cinema of that era is more than just storytelling or filmmaking. It’s a living document, preserving slices of our history, culture and social dynamics. For me, as an Egyptian, this connection feels instinctive. Yet, the sad reality is that politics today increasingly dictate our access to this past, reshaping the narratives we can revisit.

Living in Mexico City, I can’t help but compare. Here, they have four Cinetecas in just one city, all dedicated to preserving, cataloging, and showcasing Mexican and world cinema - a celebration of film as both art and archive. They’re not just places to watch movies; they’re cultural hubs. Meanwhile, in Cairo, despite the surge of new developments, we haven’t even considered building a Cinema Museum to honour and protect our cinematic legacy.

The irony struck me most when I found myself in a packed theater at a Cineteca in Mexico, watching an Egyptian film in the middle of the week, in the middle of the day. It’s a poignant reminder of how much we’re leaving behind, even as others around the world recognise its value.

If Cairo was a film, what would its opening scene be, and how would you envision its ending?

The scene that immediately came to mind is the ending - a completely demolished Cairo. It’s an exaggeration, but one rooted in truth, capturing the despair and uncertainty around us. Unfortunately, it would feel all too real, like a scene drawn from a post-apocalyptic film. This kind of haunting uncertain atmosphere was also reflected in the 1971 Egyptian film ‘A Drift on the Nile’, where a similar sense of disintegration and unease unfolds, mirroring the collapse of a city’s soul.

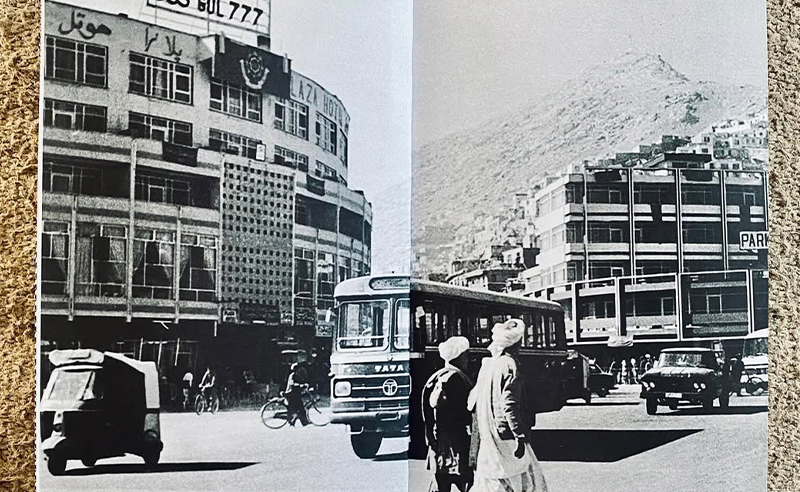

For the opening, however, I’d want to portray something entirely different - something that captures the richness and complexity of Cairo at the turn of the 20th century. I’d depict a city shaped by coloniality, integrated into a global economy that viewed Egypt not as a sovereign nation, but as a resource, a farm. This process, which began in the late 19th century, sought to align Egypt with a “global” system, one where control was centralised elsewhere but claimed to govern the entire globe.

Within this colonial framework, however, there was a dynamism and richness - possibilities in cultural and material life that defined that era. I would juxtapose the vibrant dynamism of the early 20th century with the literal and figurative flatness of the present, a flattened city and a flattened culture, where the richness of the past has been lost to the monotony of imposed global conformity.

Photography Credit: Cairo Observer