How Egypt's Mamluks Shaped the Playing Cards We Know Today

From the palaces of Mamluk Egypt to the courts of Europe, these staple cards have travelled a long and complex road.

Originally Published on December 5th, 2025

Playing cards are as integral to social life in Egypt as tea or conversation, embedded in family gatherings and moments shared on street-side cafés. Yet, few amongst us may be privy to the knowledge that these very cards - or at least, these cards as we know them today - actually trace their origins back to Egypt and the Arab world, long before they became a staple of European culture.

While Europe is often credited with developing the modern deck, the earliest form of playing cards was actually born in the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt, later spreading across the world through its merchants, only to return in a very different form. In fact, the earliest recorded term for what are now playing cards was Saracen - a word, often used in medieval times, that translates to ‘Arab’.

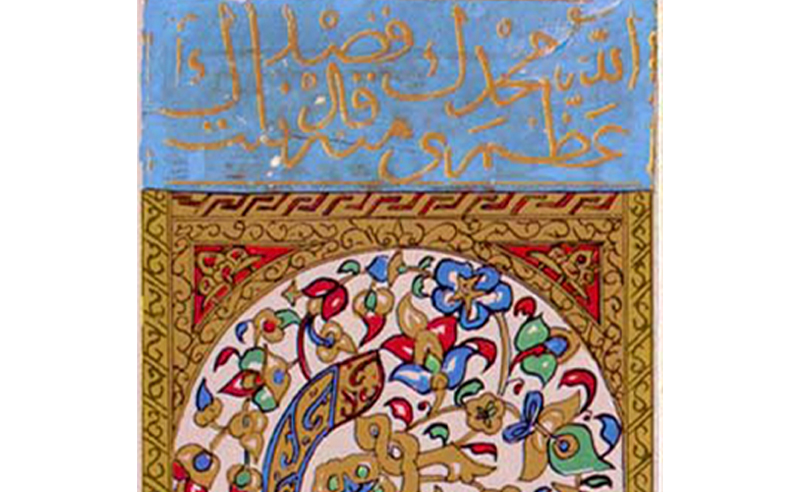

One of the most significant finds in the history of playing cards came in 1931 when historian Leo Mayer came across a near-complete set of Mamluk playing cards at Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace. This ‘Topkapi deck’, dating from the late 15th or early 16th century, provided crucial evidence linking European playing cards to their Islamic predecessors.

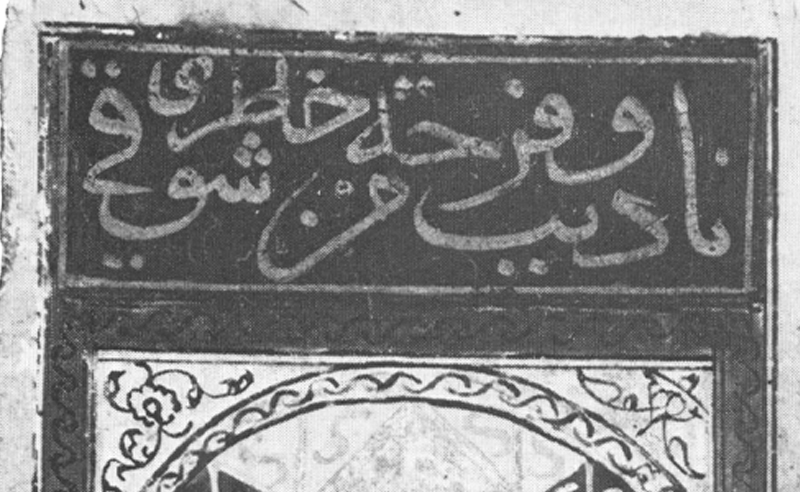

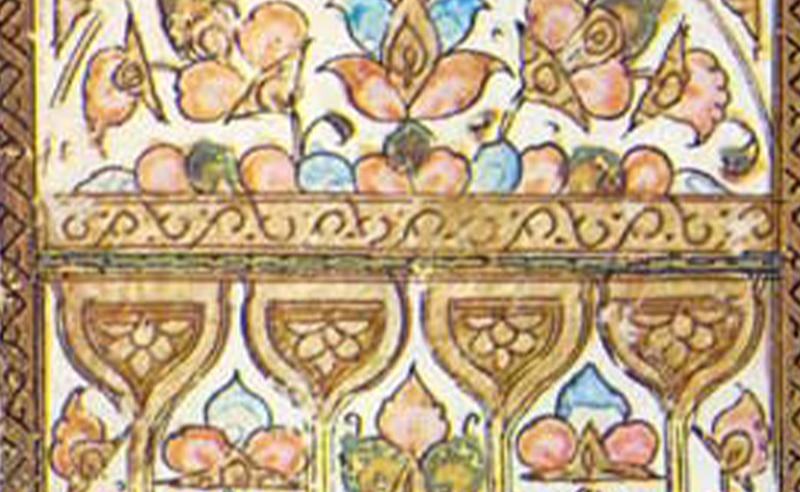

Unlike modern European decks, these cards were faceless, their beauty lying in the abstract artistry and ornate Arabic calligraphy that reflected a rich cultural heritage. Mayer’s discovery highlighted a lost chapter in the history of cards, one that demonstrated how deeply intertwined the Islamic and European worlds once were, especially through trade.

Though the origins of playing cards began in China, where early ‘money cards’ were used as a game of chance, they slowly made their way westward along the Silk Road. These cards evolved as they passed through Persia and into the Arab world, reaching their most sophisticated form in the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt in the 13th century.

Here, cards were not merely objects for recreation but also symbols of artistic refinement and intellectual engagement, designed in accordance with Islamic principle of eschewing facial depictions of sentient beings. Instead of human figures, the Mamluk playing cards were adorned with intricate geometric patterns and Arabic calligraphy, denoting the ranks of King, First Lieutenant (Naib), and Second Lieutenant (Naib Thani). The suits, polo sticks, cups, swords, and coins, were emblematic of the Mamluk court’s symbols of power and culture.

(An interesting fact to note: Mamluks’ polo sticks insignia were then turned into ‘clubs’ upon reinterpretation in Europe, seeing as the sport was yet to be introduced to the continent.)

These cards’ journey from the Mamluk courts to Europe began in the 14th century, around 1370, when Arab merchants introduced the game to European ports like Venice and Barcelona. The cards were then known as ‘Naibi’, as was the name of the game people played with them, and they quickly gained traction in Europe.

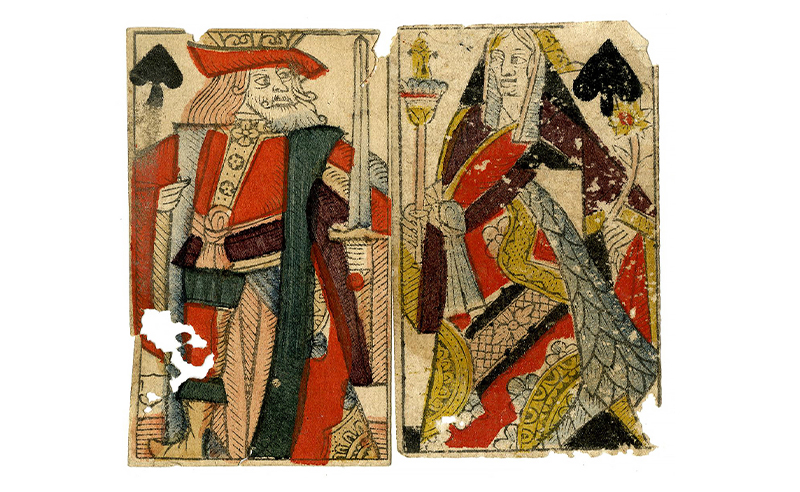

By the late 14th century, they were then recorded in Italian chronicles, signalling a growing popularity. However, as the game spread across the continent, it began to undergo specific transformations, most notably with the introduction of faces on the court cards.

European card-makers added figures of Kings, Queens and Knights, adapting the Mamluk ranks into familiar symbols of European, historical, mythological, Christian and Jewish nobility. This seemingly minor change had far-reaching implications, reshaping the identity of playing cards and distancing them from their original form.

The decision to add faces to the cards was not merely aesthetic, but also political. For Europe, which had no restrictions on depicting human figures, this transformation was perhaps inevitable. However, for the Islamic world, the move presented a significant challenge, one that perhaps may not have carried good intentions.

The Islamic prohibition against iconography meant that merchants from Mamluk Egypt could now no longer deal in European cards, creating a palpable division between the two cultures. This change came at a time of heightened tension between Christian Europe and the Islamic world, and some historians suggest that the redesign of playing cards may have been part of a broader effort to limit interaction between Muslim and European merchants.

The rift over playing cards was emblematic of a wider historical moment. The modification of playing cards, once a shared cultural artefact, became a reflection of the growing divide between European states and the Islamic state. Where once there had been faceless, abstract designs rooted in Arabic and Egyptian cultures, Europe’s addition of faces turned the cards into something recognisably Western, alienating the lands from which these cards originated.

By the 15th century, France built upon what would become the modern day deck of cards. They standardised the suits we now know as hearts, diamonds, spades and clubs, and established the hierarchy of Kings, Queens and Jacks.

This deck, with its unmistakably European influence, soon spread across the continent and eventually made its way back to the Middle East, in a form that would have been barely recognisable to the Mamluks who had first popularised the game, and would cause a great loss of identity, with Egyptians and Arabs soon forgetting where the cards they dealt came from.

The contribution to the history of playing cards is largely forgotten today, overshadowed by the dominance of the modern European deck. The faceless cards of Egypt, which once symbolised intricate art, culture and poetry, were gradually eclipsed by the more simplistic cards of Europe. Yet, to the discerning eye, the Mamluks’ influence can still be traced in the very structure of the modern deck, from the ranked court cards to the four suits.

From the palaces of Mamluk Egypt to the courts of Europe, these small, simple cards have travelled a long and complex road. Today, as we Egyptians pick up a deck today, we unknowingly deal with a piece of our own history.

Trending This Week

-

Feb 16, 2026