Irony, Ruin, and Resistance: Mohamed Al Hawajri’s Gaza Archive

Palestinian artist Mohamed Al Hawajri turns life under siege into a defiant visual language—sculpting resilience from bones, spice, and reworked masterpieces of European art history.

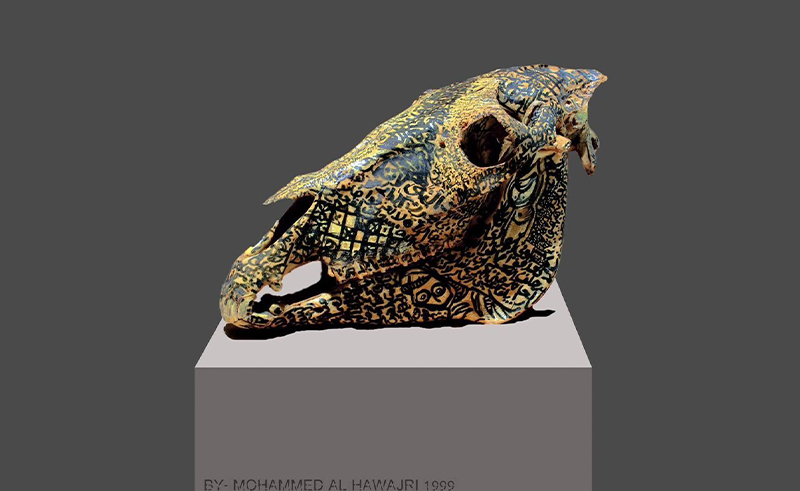

Mohamed Al Hawajri is a Palestinian artist whose creative vision has been forged in equal parts by beauty and devastation—both inextricably tied to the landscape of Gaza. His practice is rooted in the immediacy of his environment, sculpting hauntingly textured forms from the bones of animals found near his village, and rendering his community in vibrant, large-scale paintings dyed with local spices like curry and cumin. From destruction, he extracts color. From scarcity, form.

“Political art can be unappealing to engage with if it does not directly affect you,” Al Hawajri tells #CairoScene. “When people think about Palestinian art, many choose not to see it because they assume it’s only about killing, blood, and complex political subjects.”

Al Hawajri subverts that expectation not by sidestepping politics, but by folding them into a visual language steeped in irony—disarming, and therefore, undeniable.

Born in the Bureij refugee camp in Gaza during the 1970s, Al Hawajri recalls a childhood that was modest, but rich in observation. He grew up on his father’s farm, where he learned the names of birds and plants, facts he says made him feel “special” at school. He discovered his creative instincts through grief, after the death of his uncle left him searching for a form of expression that could hold his sorrow. “It felt like I lost a part of myself, and I wanted to express my love to him.” Art would soon become not only his sanctuary but his instrument—an outlet for emotional truths he struggled to voice aloud. “I was not a confrontational person. So when someone picked on me, I would draw them on the wall in a rather unappealing way—ugly or naked. That’s when I realized that art could be a good outlet to express your emotions.”

But by the time the First Intifada erupted in the late 1980s, the tenor of his surroundings—and his work—shifted. “Things started taking more of a dark turn,” he reflects. “There was no more travelling, no more moving, no more food, no more medicine. These things were no more in Gaza.”

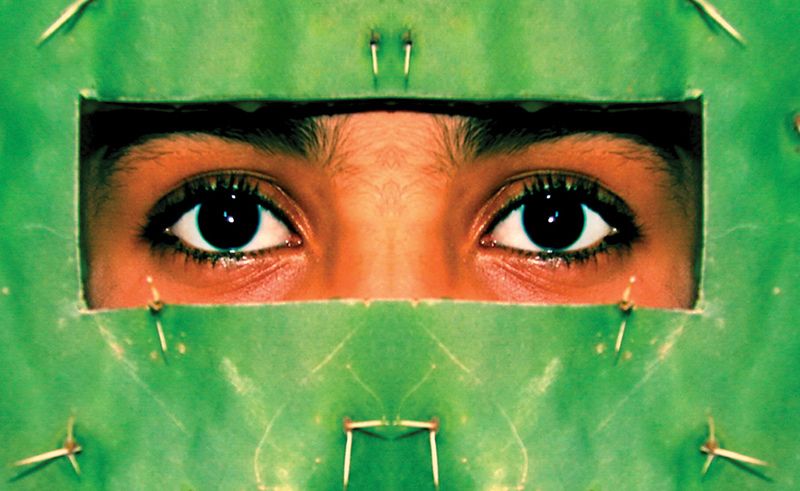

ugly - beautiful. 1999

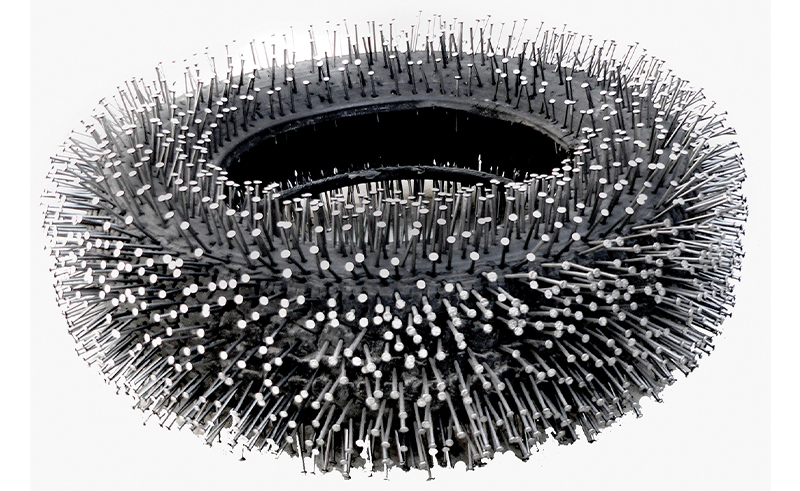

It was during this time that Cactus Borders emerged—arguably Al Hawajri’s most visceral and arresting series. Here, the artist transforms the visual grammar of occupation into a materialized language of resistance: nails, wood, and the ever-symbolic cactus coalesce into raw metaphors of survival. The cactus, a longstanding emblem of Palestinian resilience and rootedness, takes on thornier dimensions. In one sculpture, a humble flip-flop—ubiquitous across Gaza—bristles with protruding nails, turning the very act of walking into a meditation on restricted movement. In another, spiked cactus forms are mounted against coarse wooden panels, evoking both Gaza’s agrarian past and its barbed-wire present. These works do not ask to be admired—they demand to be felt. Each piece is an indictment of aesthetic detachment, a reclamation of pain rendered in physical form. Al Hawajri’s message is unequivocal: in Gaza, to create is to resist. Survival, itself, is a form of authorship.

“Just like the Palestinians, cacti live with little water,” he explains. “Wherever you plant it, no matter the resources, it will grow and thrive. Palestinians are the same—because no matter what situation you put them in, they will survive, live, and make the most of life… And if you rip a cactus out by its roots, it will still grow. It might even multiply.”

Above the city, from the series Guernica - Gaza. 2010 - 2013

In 2008, Al Hawajri was awarded an artist residency at the Cité Internationale in Paris. Yet even among fellow creatives, he struggled to find a cultural foothold. “People would visit the studio and wouldn’t even know where Palestine was on the map.” That alienation became fuel. It inspired Guernica in Gaza (2010–2011), a powerful series in which Al Hawajri recontextualizes iconic European artworks to document Gaza’s contemporary traumas. Taking Picasso’s Guernica as a conceptual lodestar, the series digitally reconstructs works by Goya, Rubens, Ingres, and Delacroix—replacing mythological and imperial subjects with bombed-out buildings, grieving families, and wounded civilians.

Cactus Boarders. 2008

In one composition, the languid sensuality of an Ingres odalisque gives way to the lifeless frame of a child pulled from rubble. In another, Goya’s famed execution scene from The Third of May 1808 is transposed onto the streets of Gaza, its figures echoing both resistance and mourning. These are not pastiches—they are interventions. By stitching Palestinian suffering into the familiar brushstrokes of Europe’s cultural legacy, Al Hawajri delivers an indictment: that art history, so often divorced from contemporary atrocity, can be a vessel for memory and reclamation. “Art should be a universal expression,” he says. “It shouldn’t just communicate with the Palestinian or Arab population—it should be expressible to the whole world, and easy to engage with.”

That universality, paradoxically, arrives through specificity. “The iconic art was somehow familiar to them, and they were curious about why it looked different—which naturally led them to learn more about these issues,” Al Hawajri explains. “The project still affects people to this day. Almost every country has been through intense war. But with time, new things happen, and people often forget the hardships their country once endured.”

Al Hawajri’s work has since been exhibited internationally, reaching audiences far removed from Gaza’s frontlines but newly attuned to its story. “You don’t want to just sell art for money anymore,” he reflects. “Art is about expression and representing yourself, your people, your culture. We need to know why people are in their situation in the first place. It’s our responsibility to depict a different and unique perspective to what people think they know.”

Since October 7th, 2023, Al Hawajri has found it nearly impossible to create. The loss of family members, the destruction of his city, the unrelenting images of war—these are wounds still too raw to be shaped into work. “I have experienced things that I can never forget. And there are much bigger issues happening.”

Red Carpet. 2015

His studio once sat atop his home in Gaza, a shared space with his artist wife. “We had 25 years of work in there,” he says, remembering what is now lost. “We also built a little garden, my wife and I, from cacti we grew over 15 years. These plants grew up with us.” Family members have since risked their lives attempting to retrieve fragments of that legacy—artworks and artifacts that belong not only to Al Hawajri, but to Palestine’s cultural memory.

Today, Al Hawajri lives in the UAE with his wife and two daughters, having secured a Golden Visa. But his story remains unfinished. “I hope to one day depict or represent what me and my family had to endure.

- Previous Article ‘My Dubai Communities’ Launched to Connect Users Across Dubai

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Jan 31, 2026