Painting ‘Development’: Dalila Hassanein’s Art as Social Commentary

Dalila Hassanein is a 24 year old artist, whose work aims to comment on the socio-political and economic realities of Cairo.

Dalila Hassanein’s Cairo-based studio is awash with the objects which she uses to create her signature textures merging a form of street art with ordinary Cairene symbolism- spray paint cans and canvases in progress abounding. Her oeuvre is as loud and colourful and messy as the Cairo streets which inspire it, the living and ever-continuing barrage of street art, murals, graffiti, brick, mortar and concrete.

Her studio is located in a quiet district on the outskirts of central Cairo. Through a cobbled path surrounded by a garden full of bougainvillaea, one enters a quiet, wooden, and warm art studio. In it, you would find oriental art depicting fellaheen, and furniture and paraphernalia inspired by Upper Egypt. It is a soft space, and a welcoming respite from the heat, not only for its stylistic appeal, but also for the eloquent artist who makes it her workspace. The youthful Dalila Hassanein, 24 years old and in her senior year of visual arts at the AUC, sits myself and my colleague down in the little kitchen adjacent to her workspace.

Hassanein hails from a family entrenched in painting and the country’s artistic history, Hasseinein’s painter grandfather was an intimate of Egyptian modern artists Hassan Fathy and Helmi El Touni. Her great-grandfather too was a pioneer, being one of the first cohort of Egyptians chosen to study at the Beaux-Arts de Paris. Hassanein’s journey into the arts was no coincidence, in fact, it may be said that the arts run in her blood. “I learnt to paint before I started speaking, it is my first language,” Hassanein tells CairoScene. Hassanein has come to acclaim of late for her work documenting Cairo’s Ring Road, and the socio-political implications of it in her art. She invited CairoScene to her studio to learn more about Dalila the artist, as well as the myriad influences and reasons which inspire her work. As much as it is art, it is cutting social commentary, as we come to learn.

Her early years were spent growing up in Montreal, Canada, after which she moved back to her native Egypt attending school in the French lycee system, before going on to pursue her tertiary studies in Strasbourg, France. It was here in France that Hassanein first became appalled at the Eurocentricity that pervades art history in the West. “We weren’t taught that the art nouveau style which proliferated Western art in the 1920s was in fact inspired by Islamic art, and that the Italian renaissance was birthed out of developments made in the Arab world,” says Hassanein.

Wanting a more holistic education, Hassanein transferred to the AUC. “They didn’t transfer my art history credits from my courses in Strasbourg. Alhamdulillah. I learnt to rethink the way I approached my own art after being educated on our own rich local artistic heritage.”

As Hassanein’s horizons expanded and she became more entrenched in the legacy of the Francophone culture in the Middle East, and more specifically, the legacy of the French occupation on the Egyptian psyche, her work took on a more political bent. “The French occupation lasted only three years, yet its negative effects have persisted for centuries. Our upper classes still see French culture and language as the aspiration,” Hassanein says. “The French, as well as the English occupations, made us look up to the ‘khawaga’ as an aspirational identity. We see it even now, where many upper class Egyptian children are raised speaking fluent English and French, and cannot speak their native Arabic properly.”

The realisation of these adverse effects of colonialism and the colonial erasure of local culture, art and architecture led Hassanein to submit a final thesis project at the AUC, which focused on the demolitions and removals around the Basatin area to make room for the Ring Road expansion, entitled ‘Whose Public Benefit?’. To Hassanein, the ‘socially useful’ project is a projection of the neglect of the actual living and breathing histories and communities which are being erased in order to again satisfy the Western notions of development and progress. “I realised in my research that the Ring Road expansion and its adjacent removals and demolitions were all down to this same colonial idea, that what the West sees as important should be important to us too. The Ring Road expansion was not so much for the benefit of the public as it was about making the city look more attractive to foreign investors, without paying attention to the gentrification which the whole project was emblematic of,” Hassanein says.

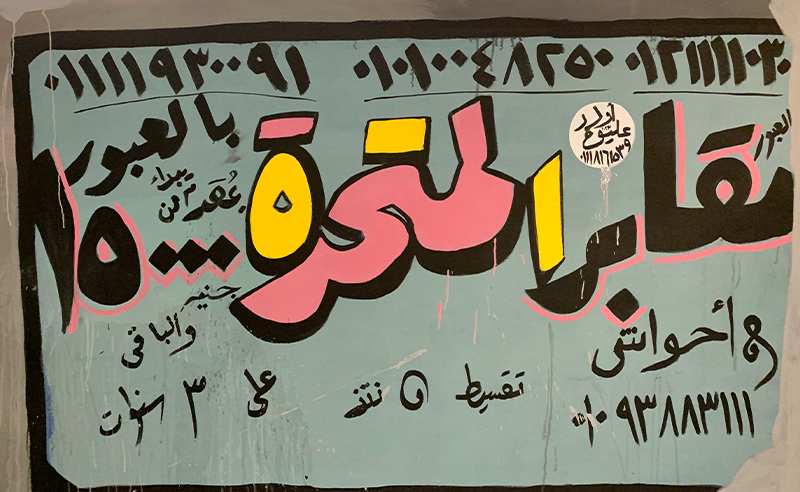

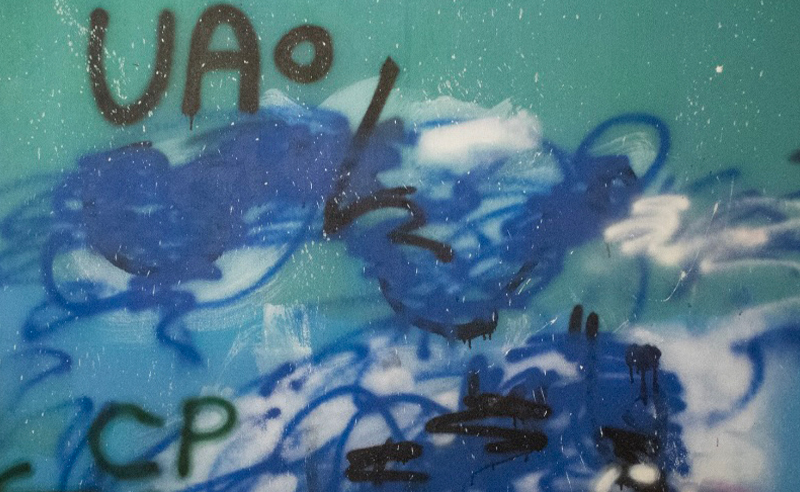

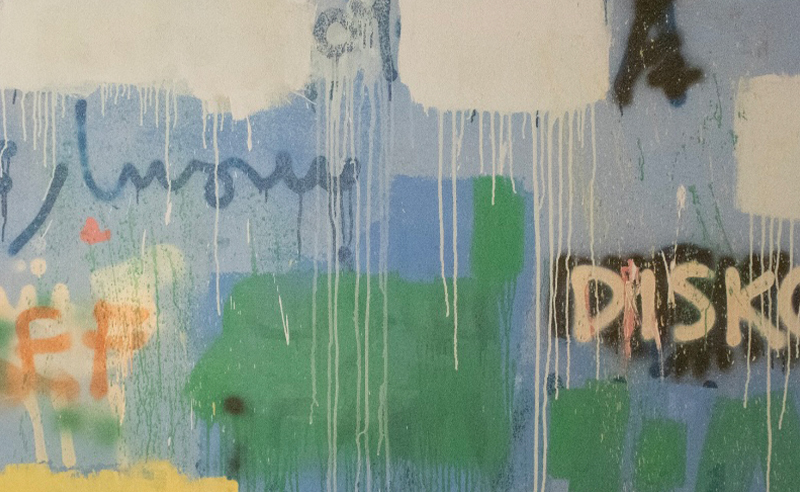

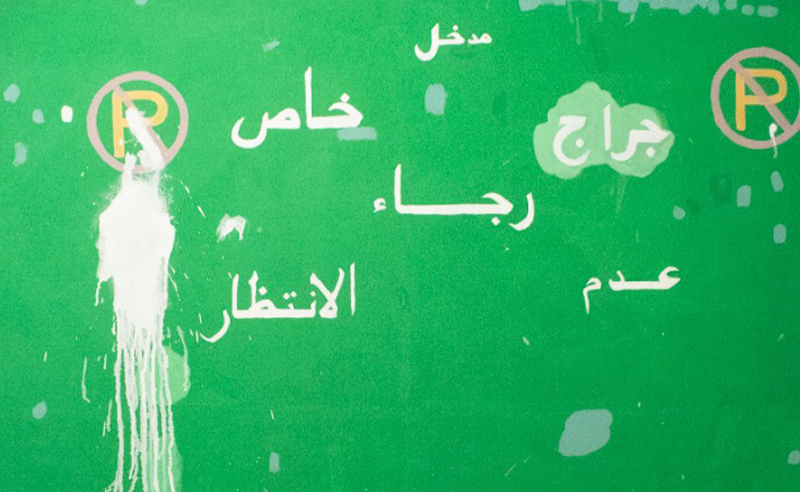

To contrast the socio-economic divisions which plague the city of Cairo, the project used the paint colours, symbols and sticker advertisements which are common on the walls surrounding the Ring Road in its more impoverished areas to highlight the disparity that pervades the city’s infrastructural and architectural set-up. “Around demolished buildings in Basatin are painted the most beautiful and light shades of pinks and blues, welcoming and soft colours. Yet they are symbols of the invisibility of these communities. They are also full of advertisements. The more East or West you go in the city, that is, to more monied areas, the colours that signify one community’s removal become the chosen colours used to beautify the villas in compounds. I found this juxtaposition an interesting commentary. The sad thing is that so called development and renovations have become more important than our heritage.”

Her commentary expands into the architecture of the city too., “The haphazard architectural styles which pervade the compounds and new developments is a further example of our own preoccupation with the West. We have a mishmash of outdated European styles, art nouveau on bauhaus on brutalism, that have no place in contemporary Egyptian architecture. We have our own styles to develop, based on our Pharaonic, Islamic and many other histories. It even goes to the nomenclature of new developments. We have compounds in Sahel called London and compounds pretending to look like a suburb of Paris. This is all rooted in a colonised mindset, and I want to comment on this.”

In much of her oeuvre there is a focus on the use of graffiti and the painted advertisements which are a commonplace sight on the walls of working-class Cairo’s buildings. “I find the use of graffiti and street art as somewhat representative of the areas in which the majority of the city’s citizens live in - that is, in the more underprivileged areas. Somehow freedom of expression is more present in these areas, perhaps because they are less sterile than the new areas which apparently represent progress,” Hassanein shares. Her interest in graffiti and street art is also related to the histories of the city, and its different epochs expressed through popular art. “I like the idea that the layers of walls have history, and if you peel them off you might find graffiti stretching back to the days of the Revolution or further back, for instance.”

The presence of calligraphic ads which make up much of Cairo’s street art is also a major fascination - here she attempts to portray the way industry has employed popular art to gain more attention to their products or services. “It is almost as if, the bigger, the more colourful, the more glittery the calligraphic ad, the more attention the business or service will get. It is powerful commentary on the way our informal economic sectors function,” comments Hassanein.

The Ring Road project is an example of what Hassanein sees as a continuation of centuries of Egyptian artists’ commentary on the change of the city and country around them. “I believe there is a requirement for artists to embrace their respective artistic heritages and their artist compatriots which came before them, there is a continuity,” Hassanein comments. “I treat art as a research paper somewhat, I ask why saying this specific thing is important, and what is its social and historical context. The canvas is as much a documentation of life as any other form of documentation,” Hassanein explains. “It is important that art should have some sort of social or political message, but I don’t think it is an absolute must. Some of the best art in my opinion is not focused on these issues and is focused simply on the human experience.” She is also artistically inspired by artists who focused on making beauty accessible in the everyday. “I am inspired by artists like Bassem Youssri and Claes Oldenburg. Oldenburg sculptures focused on finding beauty in mundanity, and Youssri’s focus is similar to mine, commenting on the surrounding environments which influence the way we live our lives.”

In essence, Hassanein’s work aims to further a decolonial art. “I once wrote a manifesto which I have now abandoned which critiqued Orientalism, and the way the West looked at Egyptians and Egyptian art as fellah. My previous work I feel to have been stagnant, automated, and rigid, based on the Western art education I received,” she shares. “I was not sure what I wanted to tackle, and the uncertainty of focus led to a mental and emotional artistic grey area. My previous work was almost just a form of therapy. Now, perhaps inspired by my unlearning the ideas that had been fed to me in my French education, I realise the importance of embracing our unique and inspired Egyptian art form. We are such a mix of diverse inspirations and heritages, not only Arab and Egyptian”

“Colonialism used the symbolism of empty land in their art to negate the existence of the native populations which they conquered, and to justify their aggressive genocides and landgrabbing. It happened in early colonial American art, and it persists today in Israeli art,” Hassanein continues. “I want to negate this vision in my work, to show how full of life and existence our lands are. Art, as much as it is used to justify colonialism, can be used as a tool to resist it.”

Hassanein’s new work, some of which are to be exhibited in February 2025, aims to comment on choreo-policing. The way we police our bodies to move based on our surroundings. “One doesn’t physically act the same on the street as one does at a wedding or at a party. The proliferation of cars in Cairo has made us, for instance, even walk differently. I want to comment on how small objects have changed the way we move,” comments Hassanein. “I noticed recently for example that on my daily walk from home to the gym, the metal rails that are used to reserve parking have obstructed the routes I take, my access to the sidewalk, and thus forcing me to be on the main road more. All of this affects the way I interact in my movement with my daily surroundings.”

Her new work also aims to expand out of painting, exploring installation, and delving into sculpture, video and audio. “Painting is my comfort zone, and I want to get out of it a bit so that my work might be more bold and more expansive.”

Thinking of the future, Hassanein says, “I hope to share my art abroad one day. All the things I comment on are not specific to Egypt, they are present globally. One day perhaps, I could go on a residency in some city abroad, and draw parallels and differences between our environment in Cairo and whatever city I am in.”

- Previous Article Italian-Palestinian Duo No Input Debuts Eponymous Electro EP

- Next Article A Century of Hospitality: Discover Egypt's Historical Hotels