Saudi Artist Nujood Al-Otaibi on Overcoming Disability Through Art

“My diagnosis impacted me, but I just didn’t show it, I didn’t want to. All that suppressed energy spilled onto my canvas.”

At the age of three, Nujood Al-Otaibi - born in Taif and raised in Jeddah - experienced the power of art for the very first time. While she can hardly recall her earliest attempts at painting, one moment in particular stands out for Al-Otaibi: watching her father paint a wave. Al-Otaibi’s young self could not fathom what she was seeing; all she knew was that her father brought the ocean to his canvas. To her, the waves were as real as they could be. This is when she knew where her heart belonged - on the canvas.

When just two years later, Al-Otaibi was diagnosed with severe hearing loss, art became her only solace, one in which she would find both success and satisfaction. In this exclusive SceneNowSaudi interview, Al-Otaibi, now 36, opens up on finding inspiration in nature, what it means to be a Saudi artist coming to terms with a disability, how her canvas has allowed her to connect with a world without sound, and why it’s pivotal to make mistakes over and over again.

When just two years later, Al-Otaibi was diagnosed with severe hearing loss, art became her only solace, one in which she would find both success and satisfaction. In this exclusive SceneNowSaudi interview, Al-Otaibi, now 36, opens up on finding inspiration in nature, what it means to be a Saudi artist coming to terms with a disability, how her canvas has allowed her to connect with a world without sound, and why it’s pivotal to make mistakes over and over again.

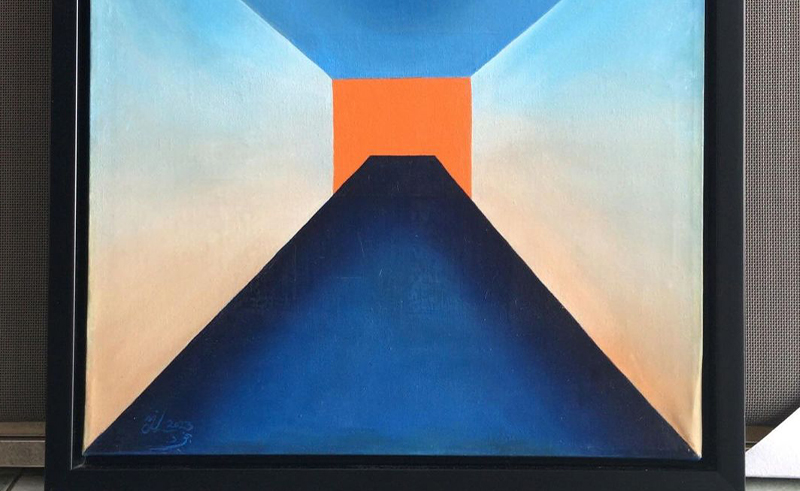

Al-Otaibi has crafted a career that speaks to resilience in the face of adversity. In the summer of 2023, she was selected as the first artist-in-residence for the McLaren F1 team’s ‘Driven by Change’ initiative. This milestone allowed her to design the livery for McLaren’s F1 cars, an abstract minimalist composition in shades of orange and blue gradients, speckled with abstract shapes in black and white.

The residency, based in Studio Thirteen in Dubai, provided Al-Otaibi with a fully funded studio space and mentorship from Egyptian artist Rabab Tantawy, who had designed the McLaren car livery for the 2021 Abu Dhabi Grand Prix. This opportunity allowed Al-Otaibi to push the boundaries of her craft and explore new artistic territories, veering from hyperrealism to abstract art.

The residency, based in Studio Thirteen in Dubai, provided Al-Otaibi with a fully funded studio space and mentorship from Egyptian artist Rabab Tantawy, who had designed the McLaren car livery for the 2021 Abu Dhabi Grand Prix. This opportunity allowed Al-Otaibi to push the boundaries of her craft and explore new artistic territories, veering from hyperrealism to abstract art.

“It wasn’t just art,” Al-Otaibi says. “It was where I could lock myself away from the world, spending hours alone in my room, away from the noise of family gatherings or street crowds I couldn’t bear to hear.”

The transition from hyperrealism to abstraction came after years of Al-Otaibi struggling with limitations in her own art. Hyperrealism, which was once an escape for her, became a boundary.

The transition from hyperrealism to abstraction came after years of Al-Otaibi struggling with limitations in her own art. Hyperrealism, which was once an escape for her, became a boundary.

“Hyperrealism was beginning to be a form of restriction, I no longer wanted to paint replicas of what I saw, I wanted to let the piece itself lead me,” Al-Otaibi tells SceneNowSaudi. “I felt like I couldn’t express myself freely, I had no room for my thoughts to breathe."

Moving to abstract art, she found the freedom to express herself without being tethered to an image. “I could just paint what I felt, not what I saw,” she reflects. The process of letting go of control and surrendering to the abstract was one that was pivotal to Al-Otaibi’s growth and personal expression. “With hyperrealism, you follow everything bit by bit, but with abstract - it’s like painting without painting, there’s no reference, you’re your own guide.”

This transition to minimalism and abstraction revealed deeper themes of identity and solitude, things Al-Otaibi had long grappled with. “Abstraction allowed me to connect with myself,” she says. “I was painting my experience of the world, not the world itself.” As she explores shapes and colours in her abstract pieces, she taps into a dialogue between her inner world and the world outside she could not fully hear.

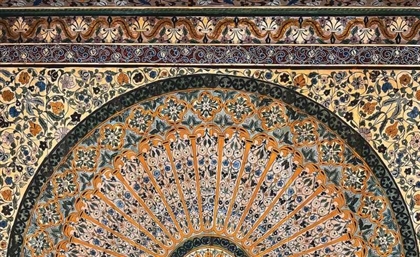

Al-Otaibi’s style, while abstract, is easily interpreted. Mountains take the forms of intertwining swirls, sand dunes hold within them lines of Arabic calligraphy, which Al-Otaibi has adopted as a signature, and sunsets are pictured in a manner that evokes a striking sense of calm. For in nature, she found her calling.

Al-Otaibi’s style, while abstract, is easily interpreted. Mountains take the forms of intertwining swirls, sand dunes hold within them lines of Arabic calligraphy, which Al-Otaibi has adopted as a signature, and sunsets are pictured in a manner that evokes a striking sense of calm. For in nature, she found her calling.

Vast landscapes have proved to be a great source of inspiration for her, especially the beaches and terrains of Saudi Arabia, where she feels most at ease - noting how only a few years back, for the very first time in her life, she could hear full conversations at the beach without her hearing aid, a moment that changed her entire perspective on art.

“Whenever I’m with more than three people and they’re speaking, it sounds like a different language entirely,” Al-Otaibi shares. “Whenever you’re somewhere with no walls, the sound travels and comes back to you clearly, and that's how I learnt to immerse myself in nature, to hear its sounds clearly.”

“Whenever I’m with more than three people and they’re speaking, it sounds like a different language entirely,” Al-Otaibi shares. “Whenever you’re somewhere with no walls, the sound travels and comes back to you clearly, and that's how I learnt to immerse myself in nature, to hear its sounds clearly.”

While the landscapes she paints indeed draw from nature, Al-Otaibi emphasises that she does not replicate them. “It’s more about the feeling of being connected to the world around me.”

Despite her success, having showcased her art in myriad exhibitions across Saudi Arabia, Al-Otaibi’s journey has been anything but straightforward. The isolation she once felt is now channelled into her art, where she continues to explore the interplay between interpretations of sound and colour, something she hopes to take further in the future with experimentation in digital art.

Despite her success, having showcased her art in myriad exhibitions across Saudi Arabia, Al-Otaibi’s journey has been anything but straightforward. The isolation she once felt is now channelled into her art, where she continues to explore the interplay between interpretations of sound and colour, something she hopes to take further in the future with experimentation in digital art.

Through her present work as an art instructor, Al-Otaibi strives to support other artists with disabilities, particularly those who may feel discouraged by societal limitations. "I want to help them reach their dreams. I need to be the support for them,” she says. "Every day I learn from my students. I see the way they express themselves, and see what they interpret as art, and it takes on so many different forms." This constant exchange of ideas with her students fuels her own artistic journey and reminds her that art isn’t about perfection. “There is no perfection in art. Where there is imperfection, there is art.”

This transition to minimalism and abstraction revealed deeper themes of identity and solitude, things Al-Otaibi had long grappled with. “Abstraction allowed me to connect with myself,” she says. “I was painting my experience of the world, not the world itself.” As she explores shapes and colours in her abstract pieces, she taps into a dialogue between her inner world and the world outside she could not fully hear.

This transition to minimalism and abstraction revealed deeper themes of identity and solitude, things Al-Otaibi had long grappled with. “Abstraction allowed me to connect with myself,” she says. “I was painting my experience of the world, not the world itself.” As she explores shapes and colours in her abstract pieces, she taps into a dialogue between her inner world and the world outside she could not fully hear.

Looking back, Al-Otaibi once envisioned success and recognition as something that would come from outside the Kingdom. “I’d always believed I’d be successful, but I thought that success, recognition, and opportunities would come from abroad,” she reflects. Yet today, she finds herself in the midst of a rapidly growing art scene in Saudi Arabia, a reality she never expected to live through. The local art community is flourishing with continuous support, and she feels grateful to witness such a transformation. “It’s a hopeful feeling to see the change that is transpiring.”

Looking back, Al-Otaibi once envisioned success and recognition as something that would come from outside the Kingdom. “I’d always believed I’d be successful, but I thought that success, recognition, and opportunities would come from abroad,” she reflects. Yet today, she finds herself in the midst of a rapidly growing art scene in Saudi Arabia, a reality she never expected to live through. The local art community is flourishing with continuous support, and she feels grateful to witness such a transformation. “It’s a hopeful feeling to see the change that is transpiring.”

- Previous Article Egyptian Designer Hassan Fikry’s Installation at Moscow Design Week

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites