The Censored Legacy of Actress Soad Hosny

In a culture striving to project unity, how did Egypt’s sweetheart come to reflect the deeper uncertainties of her times?

On her birthday, it’s worth remembering how Soad Hosny’s remarkable legacy, particularly the films that faced censorship with their unflinching portrayals of gender inequality, corruption and social unrest, collided head-on with guardianship restrictions. These films didn’t just tell stories; they asked questions. Who benefits from power? Who suffers in silence?

Although Hosny comes to mind likely in connection with the cheerful musicals and romantic comedies that endeared her to millions, her artistic range - especially starting in the 70s, the crescendo of her artistic maturity - went far beyond those familiar roles. She consistently ventured into uncomfortable terrain, resisting flattened archetypes, resisting simplicity. It’s only in retrospect that her enduring impact as both an artist and a storyteller is fully recognised with her work reflecting the complexities of her era during times of cultural and political change. Hosny’s work urged audiences to look beyond the surface with narratives gently and ungently questioning society.

Historically, film censorship in Egypt - introduced by England in 1914 - was initially justified as a political and military necessity for national security, and was later expanded in 1938, imposing strict limitations on filmmakers and prohibiting criticism of authorities or depictions of class conflict.

So, in a culture striving to project unity, how did Egypt’s sweetheart come to reflect some of the deeper uncertainties of her times?

Karnak (1975)

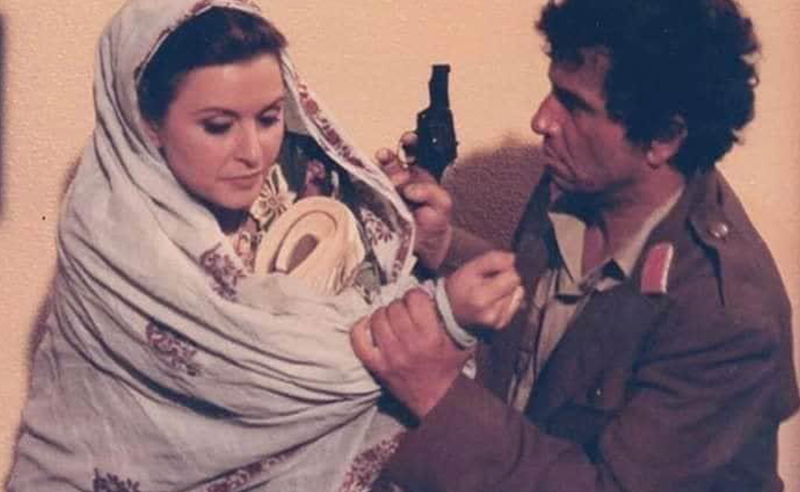

Afghanistan Why? (1983)

Ahl el Qema (1984)

Ghoraba’ (1973)

Al-Qadisiyya (1981)

- Previous Article Four Seasons Hotel Cairo at Nile Plaza Celebrates Chinese New Year

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Feb 16, 2026