The Other Albert: Egypt’s Nihilist Who Gave Camus a Run for His Money

Both saw life as absurd. Camus chose struggle. Cossery chose leisure. One pushed the boulder up; the other watched it roll by. Can indifference be more radical than revolt?

Originally Published June 27th, 2025

Somewhere in Cairo in the early 1940s, an idle figure reclines on a wicker chair, not reading, not writing, simply breathing. "Doing nothing," Albert Cossery would later quip, "is an act of revolt."

Albert Cossery stands as one of the few Arab writers to embody what might be called passive nihilism, a philosophy that mocks power, revolution, and ambition - not with rage, but with a disarming, almost elegant indifference. Born in Cairo and shaped by its languid rhythms, he would eventually make his way to Paris, where his name secured a quiet permanence in French literary circles. And yet, for all his sharp prose and radical detachment, Cossery remains a faint presence in Egyptian cultural memory, a local son more revered abroad than at home.

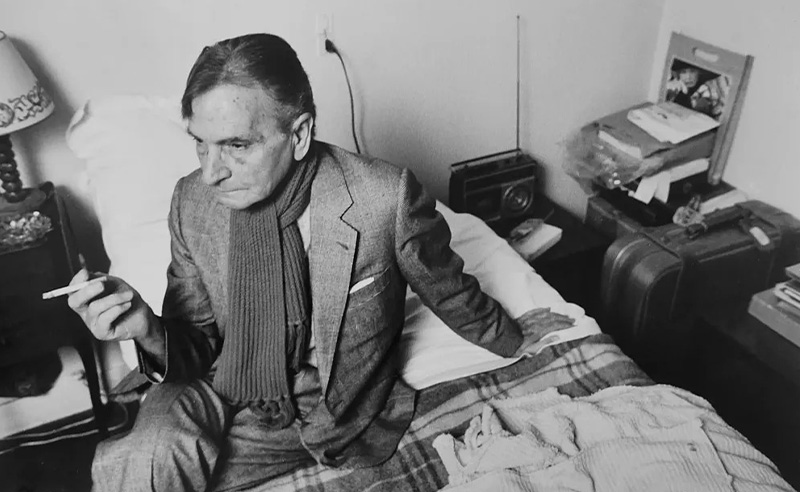

In 1945, Paris was piecing itself back together from the ruins of war. By then, Cossery had already settled into a rhythm of deliberate indifference. He lived in a small, unassuming room at Hotel La Louisiane on Rue de Seine. The space was tiny, but perfectly sufficient: a bed, a desk he rarely used, and a window overlooking the boulevard where life hustled below. Cossery lived a life measured not by accomplishment, but by the perfection of repeat ad infinitum.

In the shrine of literary Alberts, however, one name has long overshadowed the other. Albert Camus: philosopher of the absurd, moral voice of occupied France, reluctant existentialist, and grudging Nobel laureate. His name brings back visions of plague-stricken Oran and mythic Sisyphean struggles. But Albert Cossery? Even in Cairo, his birthplace, he remains, at best, a vague idea.

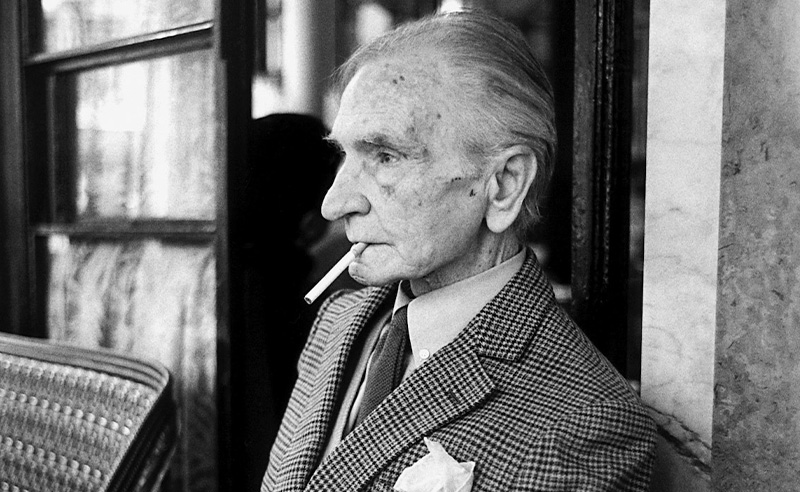

And yet, the two Alberts, Camus and Cossery, offer us a strange, inverted mirror of the 20th century. One laboured under the weight of moral responsibility in a world devoid of real, inherent meaning; the other shrugged, lit a cigarette, and asked why everyone was making such a fuss. In Paris, it was not unusual to see the two Alberts strolling side by side through the Latin Quarter, pausing at bookstalls and exchanging barbed observations over coffee. One carried the burden of the world’s absurdity; the other, its futility.

"Cossery is, in a way, the most extreme passive nihilist of all," says Léa Polverini, whose thesis at Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès charted the Egyptian writer's long, improbable career. When we spoke, Polverini painted a picture of a man at once radically disengaged and deeply embedded. "His early works still held some hope: In 'La Maison de la Morte Certaine' (House of the Dead, 1944) a revolutionary character of communist influence fighting greedy landlords, poor men scheming to overturn oppression. But with time, even that dissipates."

Indeed, by the time of 'The Lazy Ones' (Les Fainéants dans la vallée fertile, 1948), Cossery had perfected his paradox: a fiction in which no plot moves forward, because to act is to be complicit. "The more you struggle and push back through enticing an act, the more you submit to the farce of social order," as his characters imply. "Better to sit back and enjoy the sunshine."

Born in 1913 to a wealthy Syro-Lebanese family in Cairo, Cossery emigrated to Paris at 17, where he remained for the rest of his life, living most of it in the same small room at the Hotel La Louisiane in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. He published seven novels and one collection of short stories (Les Hommes oubliés de Dieu), and one collection of poetry (Les Morsures, no longer edited) over six decades - always in French, but with a vocabulary so infused with Egyptian vernacular that scholars like Frédéric Lagrange have debated whether Cossery was writing in "Arabic disguised as French."

"His language," Lagrange observes in his seminal essay 'Albert Cossery écrit-il arabe?', "has an imaginative syntax that feels Egyptian, even though the words are French." His characters speak in certain metaphors, their insults drenched in the improvisational sharpness of Cairo’s tongue. Yet the literary establishment placed him squarely within the French canon, if only on its margins.

"He erases almost any historical reference point to his novels," Polverini adds, "and this refusal is telling. His work is not Egyptian in the historical sense, nor French in the cultural one. His settings are not necessarily depictions of a certain place but stylized archetypes of power, sloth, and futility."

If Camus’s Algeria was a tortured pentimento of colonial guilt, Cossery’s Semi-Mythical Cairo is timeless in its corruption. In Cossery’s 'The Lazy Ones', a family of aristocrats idle away their days in a decaying villa, each finding new ways to avoid work, responsibility, or even thought.

The characters of 'The Lazy Ones' live this credo to the letter. They have no ambitions, no goals, not even real desires. And yet they are not entirely unhappy. Their inertia is almost erotic, their indolence bordering on a mystical state of grace. The conflict, such as it is, revolves around a character named Serag’s half-hearted attempts to break out of this life of idleness. He briefly thinks about joining a political movement, tries to seduce a woman, considers starting a business, but every time, his own cynicism defeats him. The family’s shared philosophy always pulls him back into inaction.

In the end, nothing changes. The family remains in its comfortable bubble of laziness, detached from the city’s wider poverty, oppression, and political turmoil. The villa, like their existence, quietly rots in the sun.

"At first glance, it seems like political satire," Polverini says. "But in truth, Cossery believed that nothing mattered enough to deserve struggle. His passivity was devoid of any care for ethics, because for him, even witnessing atrocities was not sufficient cause for moral indignation - he fosters a radical indifference that 'resolves' everything with unconcerned laughter.”

Here lies the essential divergence from Camus. Both recognised the absurdity of existence: life’s refusal to yield meaning, the universe’s indifference to human suffering. But while Camus made this his moral starting point, proclaiming that rebellion is the only dignified response while Cossery took it as permission to withdraw entirely.

"For Cossery, you exhaust yourself if you try to change anything," Léa remarked. "If nothing can be changed, one might as well enjoy the futile pleasures of life."

And yet, Cossery’s characters are not simple hedonists. They are ambiguous figures, convinced that their very refusal elevates them above the mediocrity they despise and mock. "They think by rejecting work and ambition they have transcended society," Polverini explains, "but in truth, they become trapped within their own inertia. They they simply play a different score of this very mediocrity they claim to escape."

This ambiguity gives Cossery’s work a strange resonance today, as younger generations confront their own version of paralyzed rebellion: the climate crisis too vast to reverse, late capitalism too entrenched to dismantle, political regimes too demonic to confront directly. The temptation of Cossery’s passive nihilism, its chic disavowal, its knowing smirk, feels dangerously seductive.

When Andrew Gallix profiled Cossery for The Guardian in 2008, shortly after his death, he called him a man whose lifestyle amounts to a "mummified existence", a self-styled voluptuous idler. In an era that fetishises hustle culture and productivity metrics, Cossery’s contempt for work reads almost radical. But his idleness was not resistance in the sense that Camus understood revolt. For Camus, to revolt was to say yes to life despite its absurdity. For Cossery, revolt was pointless theatre.

He shares with Camus the diagnosis, but not the prescription.

There is also, unavoidably, the matter of colonial position. Camus, the French-Algerian, was forever implicated in the uneasy ambiguity of the pied-noir identity. His call for moral responsibility was deeply shaped by his own proximity to, and distance from, colonial violence. Cossery, by contrast, floated above these entanglements, neither fully Egyptian nor French, his novels intentionally dehistoricised, his characters too aloof to even notice the empire that encircled them.

"In a way," Polverini suggests, "Cossery’s refusal to name regimes or dates makes his work simultaneously timeless and irresponsible. Just the spectacle of human folly endlessly replayed. Over and over and over.”

One might argue, of course, that Cossery’s work offers its own kind of critique; a satire so brutal it refuses even the solace of moral engagement. His landlords are cartoonishly greedy; his revolutionaries, bumbling opportunists; his policemen, absurd caricatures of authoritarian stupidity. In 'Proud Beggars' (Mendiants et orgueilleux, 1955), the police inspector begs a suspect to confess, not to punish him but to "give meaning" to an otherwise pointless investigation.

There is a certain grim comedy in this: the bureaucracy is so obsessed with its own rituals that it fabricates guilt simply to preserve its own sense of purpose. It is bureaucracy as metaphysical farce, a darker Kafkaesque echo filtered through the Cairo sun.

Yet to linger only on Cossery’s pessimism would overlook the strangely buoyant texture of his prose. His characters drift through corruption with a lightness that seems, at times, enviable. Life is so short. Why make it heavier with illusions of progress?

Camus offers the ethics of resistance; Cossery offers the pleasures of defeat.

Camus made this his moral starting point, rebellion as a dignified response. For Camus, the absurd doesn’t mean despair or absolute nihilism. His famous formula (in 'The Myth of Sisyphus', 'The Rebel', etc.) is: once you recognise the absurd, you must live in defiant awareness of it, through rebellion, creativity, engagement. It becomes an ethical imperative to live fully despite the absurd.

Cossery took it as permission to withdraw entirely but with nuance, not despair. Rather, they mock it, refuse to take part in its seriousness, and live lives of deliberate laziness, detachment, and ironic distance. Their withdrawal is both a personal liberation and a kind of passive rebellion, but not in the heroic or existentialist sense Camus proposes. In fact, Cossery saw inaction, indolence, and idleness as a superior response to the absurdity of oppressive power structures.

One insists that meaning must be constructed, even if the universe is deaf; the other simply leans back and watches the spectacle collapse under its own weight.

There is, of course, an unsettling edge to Cossery’s serenity. "At some point," Polverini reflects, "his indifference risks becoming complicity. If nothing matters, if no atrocity deserves indignation, then at what point does passivity enable unmorality?"

In 2008, Cossery died in Paris at the age of 94, still living in his tiny hotel room. And yet, as his novels quietly endure on the fringes of literary conversation, one suspects he maybe knew better.

- Previous Article This Agency is Turning Prom Nights Into Full-Scale Productions

- Next Article District 11: HWKN’s First AI-Planned District in Sharjah, UAE