Whirling for 190 Minutes: Inside the Mind of Egypt’s Mevlevi Leader

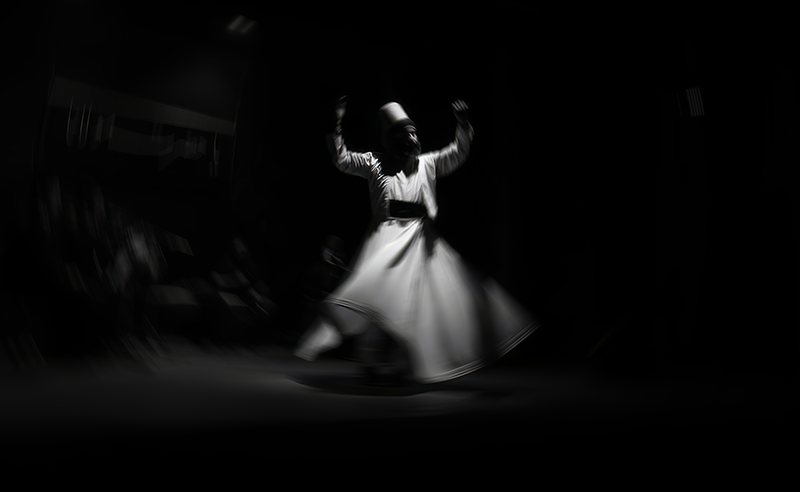

Hussein Soliman spins for three hours without faltering. In his rotation, the separation between self and divine collapses, and a century-old lineage returns to Cairo.

Hussein Soliman holds the Guinness World Record for the longest Mevlevi rotation, exactly one hundred and ninety minutes of continuous turning. Three hours and ten minutes without pause, the body maintaining its axis while the world dissolves around it. "To achieve official recognition," Soliman says, "I had to book a room, assemble a committee of witnesses, and perform under timed stopwatches." Of the rotation itself, he recalls nothing, but others told him later that the whirl lasted so long Guinness officials kept coming in and out.

Hussein Soliman did not inherit his devotion. In fact, there were no dervishes in his lineage, no mystics who had walked the path before him, no family tekke where knowledge passed from father to son across generations. He was, as he describes it, "of a very normal family"- the qualifier mattering because what followed was decidedly not. He had always maintained, he says, "a good relationship with God," though the form that relationship would take remained unclear until 14 years ago, when he saw the Mevlevi whirling for the first time.

He couldn't name what struck him - the movement itself did. Bodies rotating in measured circles, white skirts blooming like flowers, arms extended in gestures of celestial geometry. He went to Firqat Reda, the Egyptian folkloric dance troupe, with questions. "They told me it's from the folklore of Turkey," he recalls. "But later I found out it is not a product of heritage or civilisation or folklore, it's a religious practice in devotion."

He then read Jalal al-Din Rumi, the 13th-century Persian poet whose ecstatic verse gave birth to the Mevlevi Order. He read about Shams al-Din al-Tabrizi, the wandering dervish whose friendship ignited Rumi's transformation, whose mysterious disappearance, some say murder, left Rumi spinning in grief and love until the two became indistinguishable. "Here I found there are many ways in Sufism," Soliman says, "and that it's first in soul and in humans."

"God then sent me a dervish from Turkey who came to Egypt and taught me the rotation." Soliman spent 10 days in training. "I discovered it's not about the rotation, the rotation is a way to have solitary confinement with God and direct your soul into divine love. It's not about the dance. It's about what it does to you if you let it."

That was 14 years ago. He then became a Mevlevi, one who practices the turning. Then a Mevlevi dervish, a title that cannot be earned through study alone but must be recognised by another dervish who observes your soul during the circle of dhikr, the ritual remembrance of God. "You know a dervish," Soliman explains, "when 10 Mevlevi dance and one gets a connection, and then becomes not in the realm of life. If a dervish rotates and separates, in this separation, divine energy reaches the audience." Then, in 2015, exactly one hundred years after the last Egyptian head of the Mevlevi Order died, he was appointed its leader in Egypt by the Sheikh of the Order in Turkey. "The last in Egypt was Mohamed Ghaleb Dorra," Soliman tells CairoScene. "He passed in 1915. I joined in 2015, exactly one hundred years later."

Then, in 2015, exactly one hundred years after the last Egyptian head of the Mevlevi Order died, he was appointed its leader in Egypt by the Sheikh of the Order in Turkey. "The last in Egypt was Mohamed Ghaleb Dorra," Soliman tells CairoScene. "He passed in 1915. I joined in 2015, exactly one hundred years later."

The lineage Soliman inherited had been interrupted when the Ottoman Empire collapsed and Atatürk banned Sufi orders in Turkey in 1925, as part of his secularisation campaign. The tekkes closed. The whirling stopped or rather, it continued only performatively. In Egypt, the practice simply vanished. Hussein is determined to bring it all back.

"Not all Mevlevis are dervishes," he explains, "but all dervishes are Mevlevis." The title of dervish cannot be achieved through study. It emerges through recognition, one dervish perceiving another's capacity for separation, for that dissolution of self that opens onto union with the divine.

The process, Soliman says, requires vigilance. "This is why I choose the people around me. I actually look them up and see if they won't steal our energies."

"There are open energies in Mevlevi nights, and this is crucial to be preserved," he continues. "People who use energies for themselves rob it from me during the dance, and it's never fun. They take away your energy. If someone takes my energy, my field of whirl collapses."

Once, he tells me, he fell during a rotation, unusual for someone who has trained for years to sustain the turning without faltering. "I knew some yogis were in my circumference," he says. “Yogis,” he explains, “practitioners trained in manipulating prana, accustomed to drawing energy for their own purposes, extract from the open field created during Mevlevi nights. They shouldn't be greedy."

The ceremony itself follows a structure established centuries ago, refined by Rumi's disciples into what became known as the sema, literally "listening," referring to the practice of listening to music as a path to divine communion. It begins with a eulogy to the Prophet Muhammad, sung by a vocalist, establishing the devotional frame. Then comes the sound of heavy drumming representing the divine command "Be!" - the moment of creation in Islamic cosmology. A haunting improvisation on the ney, the reed flute, follows, its breathy, melancholic sound symbolising the human soul's longing for reunion with God, like a reed torn from its bed and yearning to return to its source. The dervishes enter wearing black cloaks over white robes, tall brown felt hats - the sikke - representing tombstones of the ego. They walk slowly in circles, bowing to one another, acknowledging the divine in each person. Then they shed their black cloaks, a symbolic death and rebirth into truth, and begin the turning. The right foot remains pivoted while the left propels the rotation, the right palm faces upward toward heaven, receiving divine grace; the left palm faces downward toward earth, distributing it to humanity. "The body becomes a channel between the celestial and terrestrial realms," Soliman says.

The dervishes enter wearing black cloaks over white robes, tall brown felt hats - the sikke - representing tombstones of the ego. They walk slowly in circles, bowing to one another, acknowledging the divine in each person. Then they shed their black cloaks, a symbolic death and rebirth into truth, and begin the turning. The right foot remains pivoted while the left propels the rotation, the right palm faces upward toward heaven, receiving divine grace; the left palm faces downward toward earth, distributing it to humanity. "The body becomes a channel between the celestial and terrestrial realms," Soliman says.

The separation Soliman speaks of - the moment when the dervish transcends ordinary consciousness - follows a progression he describes as a ladder. "You start by charging, you give off your black, be in white, the colour of the kafan, the burial shroud. Then you begin unifying."

The image that captures it is the infinity symbol. "Everything is suddenly black and I am light, or everything is white and I can see myself. It's being in respect with God and in reverence."

"I never imagine God," he says. "The human brain can't imagine God. But love here wins over. I see Him in characters, in gestures, in tiny things and big things. In my head, He is the Mighty God. He created eight angels to carry His throne, and between the end of the ear of one angel and the start of the neck is a walk of eight hundred thousand years. I imagine how great God must be."

Becoming a dervish, Soliman says, restructured everything. Not some things. Everything. "I became a dervish in my personal life and in my professional life. Nothing upsets me any more. God gives, God takes, and to God belongs recompense."

- Previous Article Community Matters: Safe Egypt’s New Podcast Hosted by Sara Aziz

- Next Article The Pink Inn: Dahab's First All-Female Guesthouse

Trending This Week

-

Mar 11, 2026