Khanqah of Faraj Ibn Barquq: A Testament to Mamluk Architecture

The funerary Sufi complex kickstarted the development of the Northern Cemetery and has Cairo’s largest stone domes.

In Cairo’s Northern Cemetery, amidst the historic necropolis districts, stands the Khanqah of Faraj ibn Barquq, a testament to the enduring spirit of Mamluk architecture. Built between 1400 and 1411, the Sufi funerary complex not only embodies artistic prowess but also mirrors the challenges of its time.

Constructed during Sultan Faraj’s tumultuous reign, the Khanqah rose against a backdrop of uncertainty; its construction took long by Mamluk standards due to conflicting claims on the throne. Faraj’s father, Sultan Barquq, intended for the complex to have a royal suburb in the once-empty outskirts of the city. Eventually he found his final resting place on the site in 1399, a year before the building’s commencement, laying the foundation for what would become a groundbreaking project.

Constructed during Sultan Faraj’s tumultuous reign, the Khanqah rose against a backdrop of uncertainty; its construction took long by Mamluk standards due to conflicting claims on the throne. Faraj’s father, Sultan Barquq, intended for the complex to have a royal suburb in the once-empty outskirts of the city. Eventually he found his final resting place on the site in 1399, a year before the building’s commencement, laying the foundation for what would become a groundbreaking project.

The Khanqah was not merely a tomb but a visionary effort to encourage urbanisation. Faraj and Barquq’s final resting place, the northern mausoleum chamber, became a focal point in the Northern Cemetery. The complex’s symmetrical layout, a rarity in Mamluk architecture, was made possible by its location in the open desert, defying the space restrictions faced by their predecessors in the city.

The Khanqah was not merely a tomb but a visionary effort to encourage urbanisation. Faraj and Barquq’s final resting place, the northern mausoleum chamber, became a focal point in the Northern Cemetery. The complex’s symmetrical layout, a rarity in Mamluk architecture, was made possible by its location in the open desert, defying the space restrictions faced by their predecessors in the city.

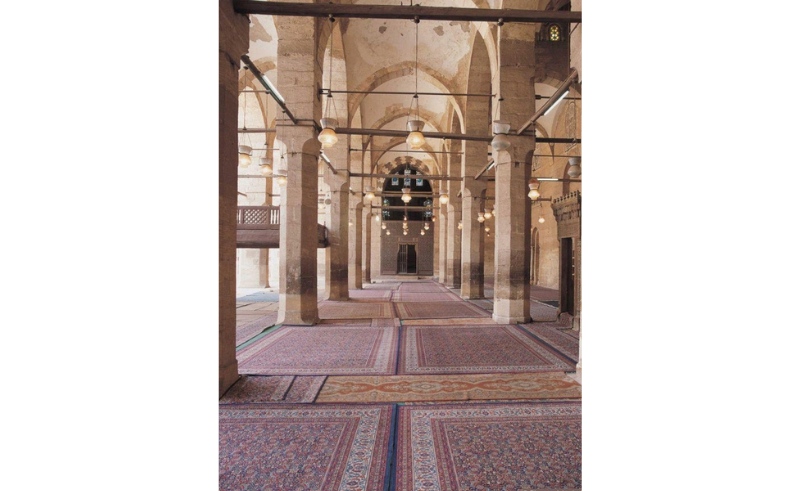

The prayer hall, surrounded by living quarters and flanked by two grand mausoleums, exhibits unique stonework, deviating from the traditional wooden ceilings of Mamluk mosques. Stone vaulted adorn the ceiling, while a stone dikka and a dome over the mihrab add to its distinctive features. Two stone minarets grace the eastern facade.

A significant stride in Mamluk architecture, the Khanqah boasts the earliest large stone domes in Cairo. The stone domes, with a diameter of 14.3 metres, remain the largest in Cairo, adorned with evolving surface decorations like chevron patterns developed during the Burji period.

The mausoleums showcase opulence through marble panelling, individual mihrabs and painted dome ceilings. Each element contributes to an aesthetic that speaks of Mamluk finesse. The Khanqah of Faraj ibn Barquq stands not only as a tribute to the Mamluk rulers but as a symbol, defying challenges of its era.

In its architectural brilliance, it beckons visitors to delve into a chapter of Cairo’s history, where creativity thrived amidst chaos, leaving an indelible mark on the city’s skyline and the legacy of Mamluk architecture.

Images Credit: Discover Islamic Art

- Previous Article Italian-Palestinian Duo No Input Debuts Eponymous Electro EP

- Next Article Boshoco Takes on a Liquid DnB Remix of Djudju’s ‘Eghtas’

Trending This Week

-

Feb 23, 2026