Le Corbusier’s Olympic Baghdad Stadium Withstood the Tides of History

Le Corbusier’s Baghdad Stadium, envisioned in 1955, weathered decades of political shifts before its 1980 completion.

In the sweltering summer of 1955, Le Corbusier received an invitation from King Faisal of Iraq - an ambitious request tied to the nation's bid to host the 1960 Olympic Games. The visionary architect was tasked with designing a grand Olympic Stadium for Baghdad, a project that he formally accepted on July 5th of that year.

Momentum gathered over the following years, culminating in official approval from the Iraqi Development Board on July 13th, 1958. Yet, fate had other plans. Just a day later, a military coup toppled the monarchy, reshaping Iraq’s political landscape overnight. Though the project was not immediately abandoned, it faced continual delays and underwent several modifications throughout the following year.

For those who find endless fascination in Le Corbusier’s functionalist and modernist visions, debating their brilliance and contradictions, his work is often inseparable from the socio-political tensions it stirs. The Baghdad stadium is no exception. Politics pulse through its very foundation, shaping both its fate and its meaning. Yet, beyond the shifting tides of power, the project also offered Le Corbusier a rare opportunity- one where he could finally bring to life some of the long-conceived ideas from his infamous ‘Radiant City’, transforming theory into built reality.

-40844462-4b2d-4e4f-ba08-3beaa1a12293.jpg)

For over a decade, the project drifted in uncertainty, caught in a cycle of revisions, shifting directives and evolving ambitions. Sketches were redrawn, concepts refined and blueprints endlessly reworked. By the spring of 1964, project engineer Georges-Marc Présenté and his team had compiled a staggering 540 drawings, which they submitted to the Iraqi government.

What had begun as a grand vision - an Olympic complex designed for 100,000 spectators, featuring a 50,000-seat stadium, a swimming pool with stands for 5,000, a 3,500-seat gymnasium, and an open-air amphitheatre for 3,000 - gradually diminished. Political shifts and logistical challenges chipped away at its ambition, stripping away key features over time. It wasn’t until 1980, long after Le Corbusier’s passing in 1965, that a spark of his vision materialised. Under the direction of his former associate, Georges-Marc Présenté, the gymnasium finally rose; a lone remnant of what was once envisioned as a monumental expression of modernist ideals.

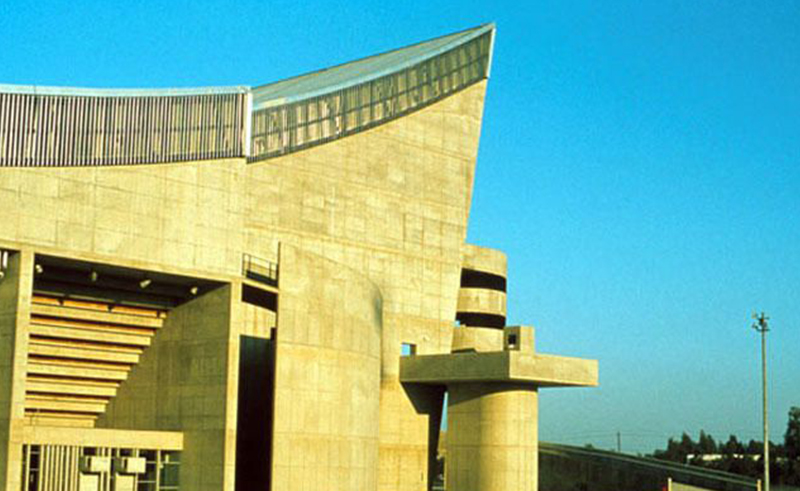

If history laid the foundation, now, the design takes the spotlight. Like much of Le Corbusier’s work, the building’s allure lies in its sculpted concrete form, a composition of bold, volumetric arrangements. Its refined lines resonate with the sheer weight of its material, creating a tension between precision and mass. Sketches suggest that the curvature of the ceiling was inspired by Bedouin tents, infusing the design with a subtle yet evocative nod to its cultural context.

The project consists of a 3,000-seat indoor stadium and an adjacent open-air amphitheater, seamlessly connected by a monumental sliding steel door. When opened, it disappears inside the structural frame allowing for the two spaces to merge into a single, unified arena. The structure commands a sense of both power and stability, yet its most striking element is the ceiling of the indoor stadium - an architectural gesture that seems to defy its own weight, gliding upward with an effortless grace, light as a feather despite the solidity of the concrete that defines it.

A sweeping, curved ramp orchestrated the approach, not just as an entryway but as a carefully framed experience - an ‘architectural promenade’ in motion. This signature design move was one Le Corbusier was simultaneously refining in another of his projects, the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard.

Beyond the main arena, the auxiliary spaces - changing rooms, bathrooms and service areas - were housed within a striking kidney-shaped concrete structure. Atop this sculpted form, Le Corbusier envisioned a roof garden, a gesture that softened the weight of the material while embodying his enduring belief in the harmony between architecture and nature.

Photography Credit: Fondation Le Corbusier and Aga Khan Trust for Culture

- Previous Article Palestinian Journalist Plestia Alaqad to Speak at RiseUp Summit 2026

- Next Article The Middle Eastern Pulse of Leighton House

Trending This Week

-

Feb 12, 2026