Manuel Álvarez Captures Architecture’s Fleeting Claim on Sacred Stone

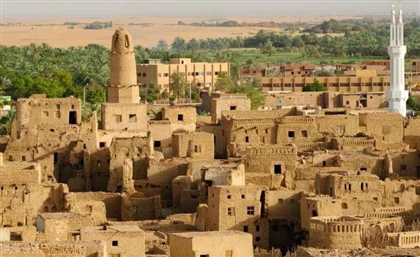

In an arid world of shifting sands, this photographer captures the raw poetry of rock and architecture in Egypt and Oman.

A perpetual struggle - man versus nature. Though they can coexist, human intervention inevitably asserts its dominance, whether intentional or not. It is simply how things unfold. Yet, in quiet defiance, nature observes - enduring, eroding, reclaiming - while human imprints fade into dust.

In this SceneHome interview, Spanish photographer Manuel Álvarez reflects on his series capturing architecture in dialogue with rock formations. We discuss human fragility, impermanence, and the unwavering, almost divine resilience of stone. From the unchecked sprawl of New Cairo to the solitude of Omani desert dwellings and the hidden shelters carved into the arid landscapes of Monegros, Spain, each structure reveals a different facet of our psyche - our desire to inhabit, to conquer, yet ultimately, our fate to yield.

-01a60a57-c4d4-43bb-b8ea-120abbf2d9c5.jpg)

What initially drew you to the relationship between architecture and natural rock formations? Was there a particular moment or experience that inspired this series?

My fascination with rock formations actually began while studying the Renaissance masters, especially Leonardo da Vinci. His paintings often use rocky landscapes not just as backdrops, but as integral compositional elements. What intrigued me was how rocks in biblical paintings weren’t just scenery; they had a presence, a symbolism, a role in shaping the narrative. When you look at da Vinci’s landscapes, they do something remarkable: they enclose the space, giving the painting a sense of unity, almost like an architectural gesture. But they also have this dreamlike quality - they seem otherworldly, as if they belong to a landscape of the mind rather than the real world.

As I travelled across the Middle East, I began to see echoes of Renaissance dreamscapes in the real world - Oman, and the Muqattam Hills in Cairo, Egypt - where rock formations felt both ancient and surreal, monumental yet fragile. Like in Joachim Patinir’s paintings, these landscapes weren’t mere backdrops but protagonists, embodying a biblical, almost mythical presence. Rocks symbolise permanence, endurance, the immutability of nature, while humans, in those same biblical narratives, embody impermanence and fleeting existence. It’s this tension between the eternal and the ephemeral that captivates me, both in painting and in the landscapes I photograph.

Your work often explores the tension between the natural and the built environment. How does this series evolve from your previous projects?

This series is, in many ways, a continuation of my previous work, where I explore the dynamic between nature and architecture. But here, I’ve taken that exploration to an extreme, almost hyperbolic level. In these arid landscapes, the line between rock and building starts to blur. The rock becomes architecture, and the architecture becomes rock. It’s a cycle - materials extracted from the earth are reshaped into structures, yet over time, those structures erode, break down, and return to the land.

This interplay between the natural and the man-made has always fascinated me. But in this series, the contrast is particularly stark: dry, unforgiving landscapes, monolithic rock formations, and buildings that seem to emerge from the terrain as if they were never constructed, but rather unearthed.

-14e8d2b1-1cfc-456f-a2bb-3fa9ac1b7bf0.jpg)

Your series captures varying degrees of integration between modern architecture and the natural landscape. How do you see this relationship evolving across different locations?

There’s certainly an element of progression in this series - a gradual shift in how buildings and rock formations interact. I see different stages of integration, where architecture and geology either resist each other or merge.

In some cases, the contrast is stark: the buildings stand in deliberate isolation, disconnected from the surrounding rock, almost as if they were foreign intrusions. But in others, there’s an overlap - a blurring of boundaries where architecture and landscape start to intertwine.

Then, there are places like Monegros in Spain, where the rock itself isn’t just a backdrop; it becomes the dwelling. Here, the built form is indistinguishable from the land, as if it was sculpted from the terrain rather than placed upon it. This shifting relationship between the man-made and the geological fascinates me - it’s a dynamic that plays out differently depending on culture, geography, and the nature of the landscape itself.

-1625b44e-4b0f-410f-88c7-934f8fb8f263.jpg)

Your photographs feel like a meditation on time—the endurance of nature vs. the ephemerality of human structures. What do you hope viewers take away from this juxtaposition?

It always comes back to permanence and impermanence. These rocks - whether we build around them, carve into them, or try to erase them - will outlast us. They hold a kind of indifference to time, while we are bound to it. Our existence is ephemeral. As I walk through these landscapes, I photograph them because, in a way, I am the architecture. I did not build the houses, but as a human being, I share in the impulse to construct them. These images speak to our fragility, our smallness, our fleeting nature in the face of geological time.

Beyond the aesthetic pull, there is a deeper reflection: the isolation, the solitude, the vulnerability of human existence against the vastness of nature. Compared to the slow, unyielding transformations of rock, we remain mere miniatures. And within that, there is something profoundly humbling.

-dd54285d-d750-45cd-ae33-0b3e08ccfcb7.jpg)

The dwellings in Monegros, Spain, are carved into rock, disappearing into the landscape, while modern desert architecture in the Middle East often stands apart, asserting its presence. What do these approaches reveal about the cultures that built them?

This tension plays out differently depending on the place. Monegros, in Spain - a stark, arid land where filmmakers set dystopian worlds. Walking there feels like stepping into a mirage. Maybe, in some subliminal way, humans want to become the rock - to possess it, to merge with something unshakable. Throughout history, we’ve carved tombs, temples, entire cities into stone, as if trying to root ourselves deeper into the earth. Maybe it’s an illusion of power. A way of taming the wild, of controlling nature, and by extension, controlling time.

In places like New Cairo or Oman’s new developments, the interaction feels more orchestrated - there’s a collective push to expand, to impose order onto the landscape. These are deliberate acts of real estate, of planning. But in Monegros, it’s something else. There, a single person might look at a rock, claim it, and carve a home into it. It’s less about expansion and more about solitude, about an individual deciding to exist in dialogue with the land rather than against it. The dialogue between human and rock is collective, a struggle between mass urbanisation and the land itself.

-682e4db2-8940-40a9-8b5e-7c11ceb71031.jpg)

You've spent time observing different ways people inhabit Cairo, from the informal settlements to the planned developments of New Cairo. What stands out to you?

The Zabaleen District in Cairo, for instance, have adapted organically to their environment. They live alongside the rocks. They don’t destroy them; they coexist with them. Even though the rocks pose a constant threat, they accept them as a fact of life. There’s a certain humility in their relationship with the land.

In New Cairo, it’s the opposite. It’s a vision imposed on the desert, not in dialogue with it. You see an army of workers arriving to construct what is imagined as paradise - without respecting the desert’s natural topography or formations. They haven’t embraced the landscape; they’ve overwritten it.

What’s been created is a suburbia - a suburban dream transplanted onto one of the most magnificent desert spaces on Earth. Of course, you’ll find nice houses, but the overarching effort has been one of control: transforming the desert into something artificial, something that conforms to a predetermined aesthetic rather than responding to the environment.

-f03270ad-1376-481a-822d-accac3b04cee.jpg)

Beyond the environmental concerns, what about the social aspect? How does New Cairo compare to older models of urban life?

Cairo’s demographic growth demands expansion - there’s no question about that. But how we expand matters. What we’re seeing in New Cairo is a model that prioritises cars over people. It’s a car-driven society, which, in many ways, contradicts the global conversation around cities of the future.

Take the idea of the 15-minute city - where everything you need is within walking distance. Imagine living somewhere where you can stroll to the movies, a restaurant, a library, a park, or a coffee shop. That’s a vision of urban life that fosters connection and accessibility.

New Cairo, on the other hand, represents the end of that era. It’s built on the romantic notion of escaping the city, finding your private garden, your personal retreat. But if that means spending two hours a day in traffic just to reach work or basic amenities, is it really a better way to live?

-0d53c2ed-75f9-40f5-a30f-a1a10b9aae49.jpg)

You’ve photographed in extreme conditions across different continents. Can you share an instance where the environment shaped the way you approached a shot or changed your perspective on the project?

To stand before a landscape is one thing. To reach it is another. These places are not found on a whim, not stumbled upon like a café after a walk through the city. They demand something of you - miles walked, altitudes climbed, heat endured, cold confronted. There are no roads that lead directly to them, no easy vantage points waiting to be framed. The journey itself is the composition.

Take Iran, for example. Some of the photos I took were from high-altitude mountain peaks - 4,000 metres up in the Alborz range, overlooking Tehran. There’s no flexibility in positioning; the terrain dictates where you can stand. You can’t just move to find a better composition - you work with the one vantage point nature allows.

In Musandam, Oman, I landed alone, rented a car, and drove without a destination, chasing the landscapes that no one could name. Even in New Cairo, I walked for hours, mapping its strange newness on foot, searching for the moment where space speaks.

The real challenge is not in taking the photograph - it is in earning it. There is an element of suffering that great photographs demand. The body bends to the land, the skin burns, the sweat stings the eyes until vision blurs. In the desert, the salt dries on my face; in Iceland and Korea, the cold cuts through layers, the air itself resisting my presence. But I love this - the collision of extremes, the body against the elements, the confrontation between self and landscape.

Everything I do is about juxtaposition. Rock and architecture. Isolation and connection. Stillness and struggle. And in that struggle, there is always discovery - not just of place, but of self. Perhaps that’s why I go alone. Because beyond the photograph, there is something deeper - an escape, an immersion, a way of finding myself in places where I feel findable.

-6fbeead3-1e69-4519-bed2-e64e08e30935.jpg)

If we compare ancient desert architecture to contemporary projects, do you think modern structures will ever acquire the same timelessness? Or are they bound to feel temporary?

In the shadow of ancient landscapes, modern architecture often feels ephemeral. A newly built museum, no matter how grand, will last perhaps 300, 400, 500 years - briefly, when set against the permanence of the pyramids. Those stones, shaped by time and weather, will endure far beyond our constructions. The question, then, is whether contemporary buildings can transcend their temporality - whether they can achieve something akin to the pyramids’ presence, an architecture not merely of its time, but beyond it.

Too often, modern structures appear as if dropped from the sky, indifferent to their surroundings. In the deserts of Oman or the vastness of Cairo’s sprawl, they stand in stark juxtaposition to the landscape. What if, instead of imposing, they integrated? The rock is not an obstacle - it is an opportunity. The finest architects have always known this. Frank Lloyd Wright, given a pristine stretch of land, built Fallingwater not beside the stream, but over it. The structure and the site became inseparable.

-c862ecbc-ff3b-44f1-ab61-fe4e012bcbd8.jpg)

What can architecture learn from the historical and spiritual relationship between humans and natural landscapes?

There is something elemental - almost mystical - about living alongside stone. To climb, to adapt, to wake each day in the shadow of rock is to develop a quiet resilience, an understanding of scale and time. The world’s great spiritual traditions have long sought solace in the mountains, in caves, in monastic retreats where human presence is dwarfed by the land. What, then, should modern architecture learn from this?

Perhaps it begins with reverence. Not carving away the rock, but embracing it. Not erecting alien structures, but finding a way to belong. In an era of rapid construction and fleeting monuments, permanence is a rare and precious thing. The stones, patient and unyielding, will always outlast us. The question is whether our buildings will honor them - or merely stand beside them, waiting to be replaced.

Photography Credit: Manuel Álvarez

- Previous Article New App ‘Nawat’ to Boost Menopause Support Across Arab World

- Next Article Bascota Exhibit Pays Homage to Iconic Egyptian Photojournalist