Riyadh’s Tuwaiq Palace is a Historic Love Letter to Saudi Heritage

The Aga Akhan Award winner is currently being given a new lease of life as a luxury hotel.

In the heart of Riyadh’s Diplomatic Quarter, where the city’s modern ambitions converge with its deep-rooted heritage, stands Tuwaiq Palace—a masterful embodiment of architectural sophistication and cultural dialogue, introducing Saudi to the international community. Completed in 1985, this seminal Aga Khan Award-winning project emerges as a bold response to a complex brief and an audacious departure from the ubiquitous westernised architectural tropes that dominated Saudi Arabia's skyline in the late 20th century.

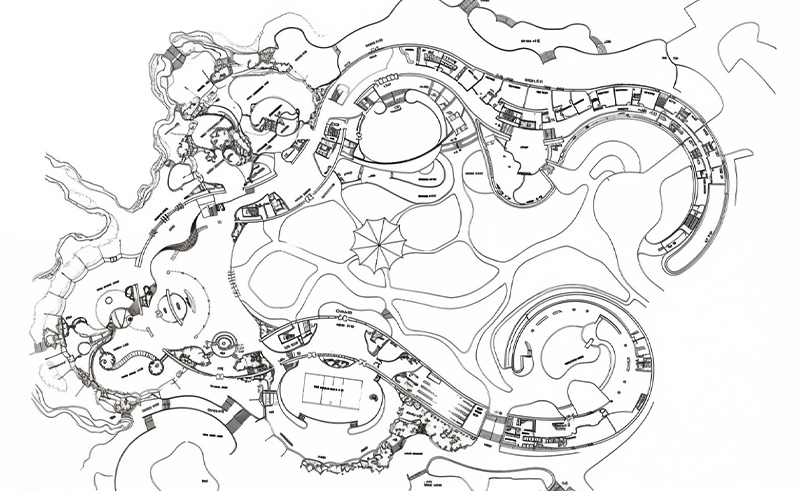

In 1981, amidst Saudi Arabia's pivotal evolution on the global stage, the ArRiyadh Development Authority (ADA) - a city development authority within the Saudi government hierarchy now known as the Royal Commission for Riyadh - initiated an architectural competition that would become a landmark moment in the nation's cultural and architectural narrative. This competition was not merely a call for design submissions but a deliberate inquiry into how contemporary architecture could converse meaningfully with the rich heritage of the Najd region, to create a contemporary cultural hub on a 24,000 metre squared plot of land situated on a promontory site overlooking the historic Wadi Hanifeh below.

The ADA's competition brief was unambiguously stringent, encouraging designers to imagine a building in the desert that respects its surrounding environment in terms of ‘forms, scale, and materials.’ The authority’s directive also demanded that the project should transcend mere historical mimicry, seeking instead an innovative synthesis of traditional Saudi architectural elements with modern design sensibilities. In fact, the brief relayed a warning: “any form of revival style or copying traditional patterns and details in old or new materials, thus creating false neo-orientalism, will not be accepted.” This stipulation aimed to foster a new architectural language that respected the region’s heritage while addressing its contemporary needs and aspirations.

The competition attracted an impressive roster of global architectural and engineering firms. Amongst the submissions, two proposals caught the jury’s attention. The first, from Omrania & Associates, a burgeoning Saudi architectural firm, showcased a deep understanding of the local context. The second, a collaborative effort between the British engineering firm BuroHappold and distinguished German architect Frei Otto (most known for his innovative design of Munich Olympic Stadium’s roof for the 1972 Summer Olympics), presented a vision characterised by pioneering structural innovation and a profound respect for the environment.

Rather than selecting a single proposal, the ADA recognised the complementary strengths of these submissions and declared both projects winners. The teams, also suitably impressed with each other, decided to marry their divergent yet harmonious visions and the consortium was tasked with the design and oversight of the Diplomatic Club—later known as Tuwaiq Palace.

The design of the Diplomatic Club is deeply rooted in the region’s historical and environmental context, drawing inspiration from two enduring Najdi archetypes: the desert fortress and the Bedouin tent. These elements reflect the historical resilience of desert civilisations and their adaptive strategies to the harsh climate.

“What attracts you to Tuwaiq Palace is the relationship between the interior and exterior, what you see on the inside and outside, the proportions, the combination of the materials, the rise and fall from one place to another,” revealed Omrania founder and Chairman Basem Al-Shihabi in a 2022 mini-documentary produced by the Saudi Ministry of Culture.

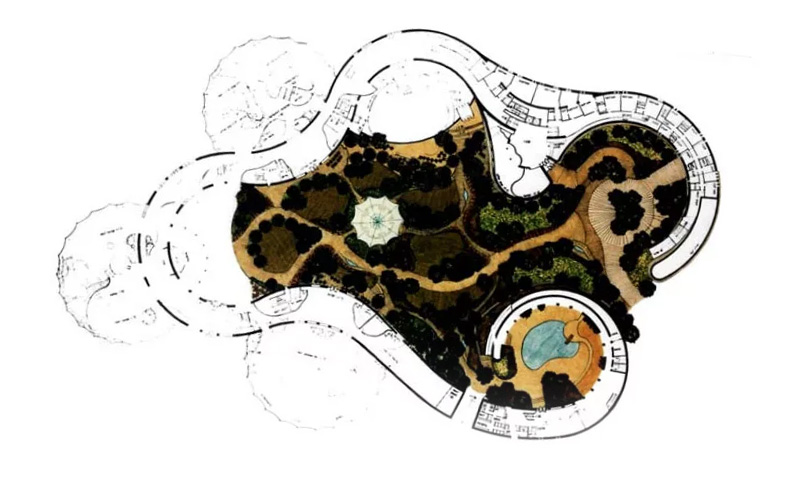

Central to Tuwaiq Palace's design is the ‘Living Wall,’ an 800-metre-long, sinuous structure that forms the backbone of the building. This innovative feature encircles a lush, internal garden, its robust and monumental exterior evoking the solid, protective qualities of a fortress. Yet, the Wall’s integration into the natural landscape is seamless thanks to its Riyadh limestone masonry, echoing the local terrain’s colours and forms, and ensuring a harmonious coexistence with its surroundings.

The interior experience is equally dynamic. Within the serpentine Living Wall, a series of flowing, interconnected spaces provide a constantly evolving environment. Grottoes and walkways create an intriguing interplay of light and shadow, offering visitors a range of spatial experiences that blend formality with playfulness. The rooftop walkway provides a breathtaking vantage point, offering expansive views over Riyadh and the surrounding rocky plateaus.

Three Teflon-coated fibreglass tents and two ceramic-tiled cable tents mushroom from the Wall, each serving distinct functions. The tents, fanning outward from the Wall, house key public areas such as lounges, reception halls, restaurants, and a café. Designed with a double-skin system, the Teflon tents manage solar heat gain while allowing ample light to support interior vegetation. Between the heavy Wall and the lightweight tents, the Palace is home to multiple microclimates.

The landscaping at Tuwaiq Palace further enhances the contrast between the lush internal garden and the arid external plateau. Inside, a meticulously designed promenade offers shaded areas, pavilions, diverse plantings and water features, creating a tranquil oasis. Outside, the expansive landscape reveals dramatic natural forms—ravines, cliffs and rock formations—contrasting with the Palace’s verdant interior and framing the distant city skyline.

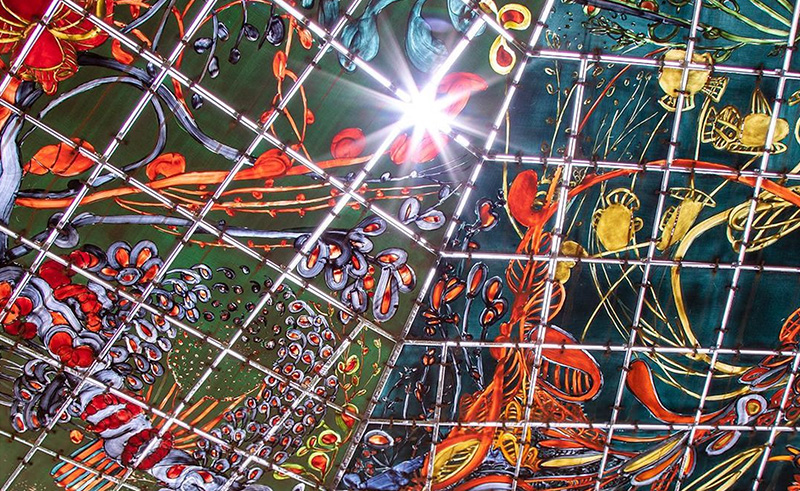

The Palace’s true gem, however, is the Heart Tent. The giant mushrooming tent, with its 2,000 tiles and reflective fibreglass coat, was a labour of love, hand-painted - one tile at a time - by Otto’s daughter, Bette. Much like her visionary father, Bette was fascinated by nature, which inspired her art. Each of the tent’s pillars is a love letter to a different ecosystem, with a pillar dedicated to corals and jellyfish, another to local flora and fauna, and so on. The result is nothing short of magical, with sun rays dancing through the multi-coloured tiles producing effervescent shade. The Heart Tent is, possibly, one

By incorporating aspects of traditional Najdi architecture—introverted courtyards for privacy, thick stone walls for thermal insulation, and small window openings to minimise solar gain—the Palace creates a contemporary building that pays homage to its cultural roots.

Tuwaiq Palace quickly gained global attention for its state-of-the-art design and was nominated for the 1996-1998 cycle of the Aga Khan Award, where it won. The reason for its success - like all Aga Khan Award winners - is the designers’ diligence in going above and beyond the brief’s requirements. Omrania, Otto and BuroHappold attempted to circumvent the brief’s warning by creating a literal juxtaposition whereby heavy hand-cut masonry gave way to light tents, verdant oases bled into golden desert dunes and welcoming ‘madyafa’ like spaces carefully concealed more private and intimate lounges, creatively sidestepping neo-historical pastiche.

“The [Palace] represents an exemplary synthesis between paying deep respect to Arabic culture and heritage (in the true sense of tradition) and using contemporary technical and formal means with highly innovative boldness,” Aga Khan award nominator Professor Dr. Wilhelm Kücker commented.

For nearly four decades, Tuwaiq Palace was home to an array of recreational, social, dining, conference and accommodation functions; including a tenpin bowling alley, crèche, billiards, library, secretariats and hotel rooms as well as club facilities like swimming, tennis, squash, sauna, gym, lounges, social rooms and formal and informal dining. While the Palace served the Diplomatic Quarter, it was also a tourist attraction site, inciting the curiosity and fascination of thousands over the years.

In January of 2022, the Public Investment Fund launched a new luxury hospitality firm, Boutique Group, to transform Saudi’s historic and cultural palaces into ultra luxurious hotels to diversify the kingdom’s hospitality experience. It was also revealed that Boutique Group will kick off with three palaces, Jeddah’s Al Hamra Palace and Riyadh’s Tuwaiq Palace and Al-Ahmar Palace, with the sites expected to offer 244 keys, including rooms, suites and villas.

Tuwaiq Palace is expected to reopen in 2025.

- Previous Article Italian-Palestinian Duo No Input Debuts Eponymous Electro EP

- Next Article Travel Across History on Egypt's Most Iconic Bridges

Trending This Week

-

Dec 23, 2025