The Evolution of Minarets in Saudi Arabia

We take a deep dive into the history of minarets in Saudi Arabia, and how they reflect centuries of cultural exchange.

Amidst the vast deserts and shifting sands of Saudi Arabia, minarets punctuate the skyline. Shaped as much by cultural exchange and material realities as by devotion itself, these towers can be viewed as vessels of transformation. From their earliest forms, austere and pragmatic, to the intricate designs that would later define entire regions, the evolution of the minaret in Saudi Arabia is a story written in stone and adobe.

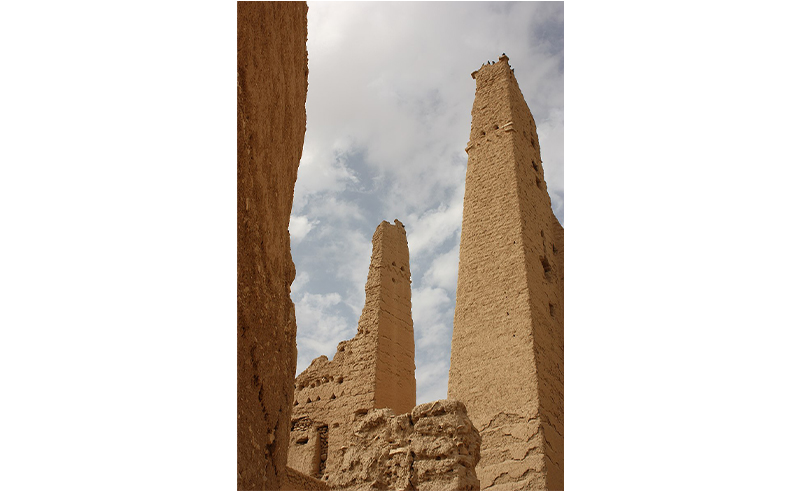

The earliest minarets in what is now Saudi Arabia were unassuming. In the harsh, arid landscapes of the peninsula, form followed function. Mudbrick was often the material of choice, its abundance and malleability lending itself to straightforward, tapering towers. These minarets were square in plan, their design dictated by practicality rather than aesthetics. The voice of the muezzin, calling the faithful to prayer, was their primary concern, and their height was sufficient to carry sound across the open desert. Ornamentation was minimal, limited to small perforations near the top for ventilation or light. These were structures born of necessity, their beauty residing in their stark simplicity.

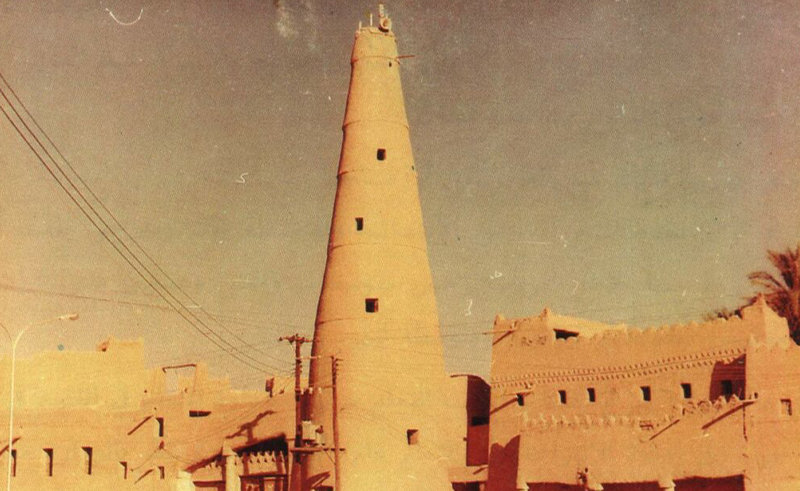

But nothing in architecture remains untouched by the world around it. As Islam spread and its reach expanded, so too did the ambitions of its builders. In the central Najd region, where the desert stretches wide and uninterrupted, the minarets retained their angular, pared-back forms for centuries. Constructed from adobe, they were practical and robust. Their thick walls insulated against the searing heat. The designs remained geometric and restrained, with little in the way of ornamentation. Even so, there was an understated elegance in the way light filtered through narrow niches, casting patterned shadows on the sand.

In the western Hijaz region, however, the story was different. Here, proximity to the Red Sea and bustling trade routes brought influences from far beyond the peninsula. The minarets of Makkah and Madinah began to reflect the tastes and techniques of Ottoman and Mamluk craftsmen, who brought with them a flair for intricate detailing and soaring, cylindrical designs. The slender minarets of Al-Masjid an-Nabawi in Madinah, capped with pointed finials and embellished with carved stone or tilework, stood in stark contrast to the squat, unadorned towers of the interior. These were structures that spoke not just of faith but of power and connection—a testament to the Hijaz as a cultural crossroads.

As the modern era dawned, the minaret underwent yet another transformation. The discovery of oil and the subsequent economic boom brought new materials, new technologies and new ideas. Reinforced concrete replaced mudbrick and adobe, allowing for unprecedented heights and more daring designs. Minarets could now stretch higher, their forms unburdened by the limitations of traditional materials. In cities like Riyadh and Jeddah, sleek, modernist interpretations of the minaret began to appear, their clean lines and minimalist aesthetics reflecting a nation looking forward rather than back.

Yet even in this push toward modernity, the minaret remained tethered to its origins. Traditional motifs - geometric patterns, arabesques, and Quranic inscriptions - persisted, often reimagined in new materials or scales. The interplay of old and new became a defining feature, as architects sought to honour the past while embracing the future. This tension is perhaps most evident in the design of the King Abdullah Financial District Mosque in Riyadh, where the minaret’s angular, abstracted form nods to traditional Najdi architecture while asserting itself as thoroughly contemporary.

The reasons for these shifts in design are as varied as the forms themselves. Geography, of course, played a crucial role; what worked in the humid coastal regions of the Hijaz was often impractical in the dry, unforgiving deserts of Najd. The availability of materials was another factor. Stone, plentiful in the western mountains, lent itself to intricate carvings and durable structures, while the central desert’s reliance on adobe necessitated simpler, more functional forms. Cultural exchange, too, left its mark, with each new dynasty or empire bringing its own aesthetic sensibilities.

Beneath the external forces lies something deeper, something that transcends the specifics of time and place. The minaret, for all its variations, remains fundamentally the same: a structure designed to connect the earthly and the divine. Whether a simple mudbrick tower or a gleaming modern spire, it serves as a visual and spiritual anchor, drawing the gaze upward and reminding the faithful of their place in the cosmos. It is this continuity, as much as its evolution, that makes the story of the minaret so compelling.

- Previous Article Red Sea Global to Launch Saudi AI Fund With Bunat Ventures

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Feb 07, 2026