The Middle Eastern Pulse of Leighton House

This Victorian painter’s London home, filled with mosaics, tiles and sculptures, reflects his fascination with the Middle East.

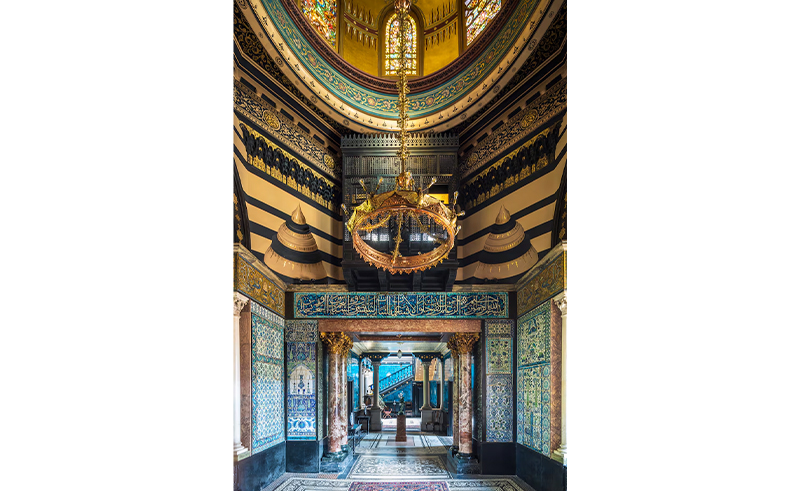

The Arab Hall at Leighton House came into being as a place to hold Frederic Leighton’s ever-expanding collection of artifacts gathered during his journeys through the Middle East.

-880c9aee-fda8-4f90-b4c7-e61c75366b2d.jpg)

The Victorian painter was admired for his sweeping academic works that drew on historical, biblical and classical themes. His art commanded high prices and great popularity during his lifetime. Though his name dimmed in the years that followed with them, his art remained, as did his home, which still bore witness to both his creativity and his penchant for collecting.

-d2157d01-f7d1-4181-b07d-8d2859343e7a.jpg)

The structure of the main house was simple. From the outside, it appeared as any other red brick Victorian house in London’s Holland Park. The ground floor was composed of a dining area and a drawing room - uncomplicated spaces that served their purpose. Upstairs, the studio was expansive, with a modest bedroom. Every aspect of the design aimed to maintain a delicate balance of work and rest.

-cd41f2da-96b6-4d16-bc08-ec8a963630ab.jpg)

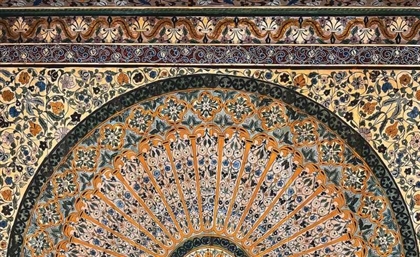

The Arab Hall however served as an extension to the house which Leighton and his architect George Aitchiso worked on together, taking every aspect of it to heart. They drew from designs they often walked past in cities like Palermo, Granada, Istanbul, Cairo and Damascus during their trips there from 1868 to 1874.

The two would go on to enlist the help of peers and colleagues to gather more tiles, and in 1877, their friend Caspar Purdon Clarke, who would later become the director of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, acquired two panels with grape motifs in Damascus, which were added to the hall’s West wall.

-d5250520-f66f-40cc-b64f-f08c32b1efa9.jpg)

The exterior features wooden screens, or a mashrabiyya (depending on who you ask), along with a metal spire crowned with a crescent - a design familiar to pretty much anyone who has walked the streets of an Arab country.

-e0cdc5d1-4056-41ba-a1be-845460b09a6b.jpg)

Inside, the high ceilings with their wooden beams exude a sense of timelessness. The mosaic draped walls carry a border of interlinked flowers, possibly drawn from the mosaics of Al Aqsa’s Dome of the Rock. Alongside them, several geometric and floral patterns unfurl in rich shades of blue, green and gold. The space also has period appropriate furniture like low divans, ornate wooden chairs and inlaid tables, all of which are functional yet very much steeped in history.

-ffc319eb-2a54-405a-b524-57c32ea1f06e.jpg)

Unlike much of the decor, the chandelier and fountain in the Arab Hall were both products of London craftsmanship. The chandelier, which was made by Forrest and Son, drew inspiration from a fixture Leighton had admired in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus. The fountain on the other hand had a central jet that splashed water into the basin, where goldfish swam peacefully (Well sort of peacefully, at least - as the story went, Leighton’s friends would inevitably fall in the fountain).

-e8edce4c-0bfb-49ed-a770-f95e07987878.jpg)

The painter’s fascination with tiles began during his 1867 trip to Turkey and Greece, where he acquired a number of Iznik ceramic plates in Lindos, Rhodes, which found their place on the walls of his dining room. Over time, his collection grew, yet not without criticism.

-a2d68185-f909-4075-aa41-d2e1f8d70582.jpg)

In recent years, scholars have raised concerns, accusing him of orientalism and the exploitation of Middle Eastern culture. The question of the Arab Hall’s purpose, to Leighton, had always been simple though. According to Leighton House’s website, he had once explained it away, saying it was “just a little addition for the sake of something beautiful to look at once in a while.”