Tracing the Architectural Legacies of the Islamic Madrasa

From Fez to Hyderabad, explore how historic madrasas shaped architecture, learning, and urban life across the Islamic world.

From Morocco’s Marinid splendour to the geometric clarity of Central Asia, the madrasa stands as one of the most enduring architectural typologies of the Islamic world. Beyond their role as educational institutions, these structures functioned as mosques, civic anchors, and centres of patronage—each revealing the material language and cultural vision of its era.

Bou Inania Madrasa – Fez, Morocco

Set within the dense fabric of Fez, the Bou Inania Madrasa (1350–1355) represents the height of Marinid craftsmanship. Designed as both a college and a congregational mosque, its symmetrical plan organises dormitories, domed halls, and a prayer chamber around a marble courtyard. The façade integrates a minaret and a once-operational water clock—an urban gesture linking time, learning, and devotion.-50b36cc1-2471-453f-9f41-50f3466173cc.jpg) Inside, every surface unfolds in intricate layers of zellij tilework, carved stucco, and cedarwood panels. The interplay between geometric rhythm and light recalls Nasrid precedents from the Alhambra, yet here it is reimagined within a religious setting.

Inside, every surface unfolds in intricate layers of zellij tilework, carved stucco, and cedarwood panels. The interplay between geometric rhythm and light recalls Nasrid precedents from the Alhambra, yet here it is reimagined within a religious setting.

Mir-i-Arab Madrasa – Bukhara, Uzbekistan

-7592a823-b659-45a9-86c2-ca0ab724aaa1.jpg)

Built between 1534 and 1539 by the Shaibanid ruler Ubaydullah Khan, the Mir-i-Arab Madrasa defines the skyline of Bukhara’s Po-i-Kalyan ensemble. Measuring 73 by 55 metres, its monumental façade is a composition of turquoise-tiled iwans, glazed mosaic faience, and symmetrical courtyards—a reflection of Central Asian architectural order.-7f97c39d-c7ff-4a1b-86c9-46da3af629ae.jpg) The madrasa follows the four-iwan layout developed in Iran, but its proportions feel distinctly grounded. Corner masses rise squat and firm, giving the structure a defensive silhouette, while two turquoise domes—one sheltering the tomb of Sheikh Abdullah Yamani—anchor the complex in serene balance. Inside, honeycombed student cells (hujra) surround a contemplative courtyard, the patterned surfaces mediating between austerity and ornament.

The madrasa follows the four-iwan layout developed in Iran, but its proportions feel distinctly grounded. Corner masses rise squat and firm, giving the structure a defensive silhouette, while two turquoise domes—one sheltering the tomb of Sheikh Abdullah Yamani—anchor the complex in serene balance. Inside, honeycombed student cells (hujra) surround a contemplative courtyard, the patterned surfaces mediating between austerity and ornament.

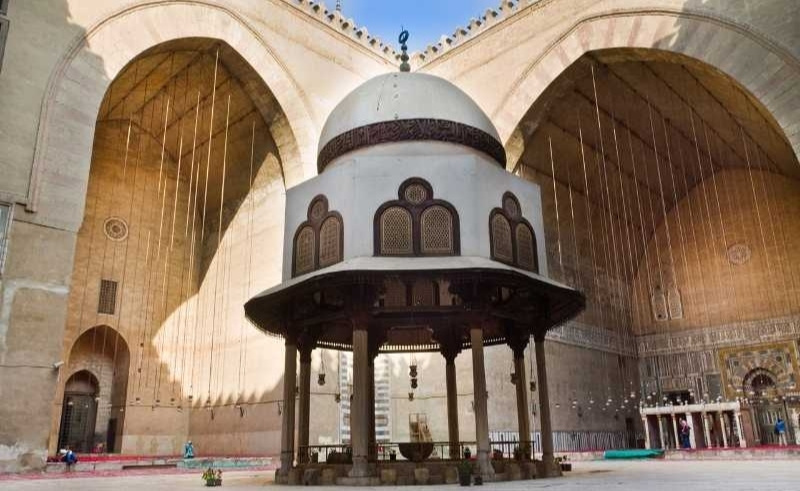

Sultan Hassan Madrasa – Cairo, Egypt-4ed67617-a77b-4936-b0a1-1685ce94a450.jpg) Dominating Cairo’s skyline below the Citadel, the Sultan Hassan Madrasa-Mosque (1356–1363) embodies the ambition of Mamluk monumentalism. The building’s soaring façades and deep, muqarnas-framed portal establish a vertical drama unmatched in medieval Cairo.

Dominating Cairo’s skyline below the Citadel, the Sultan Hassan Madrasa-Mosque (1356–1363) embodies the ambition of Mamluk monumentalism. The building’s soaring façades and deep, muqarnas-framed portal establish a vertical drama unmatched in medieval Cairo.-31e97125-7c61-44e6-a424-e07c9cee2fda.jpg) Organised around a vast courtyard with an ablution fountain at its centre, the four-iwan plan accommodates madrasas for each Sunni school of law. The qibla iwan rises to commanding height, its scale reinforcing spatial hierarchy. Student cells are aligned along the outer walls—each window contributing to the rhythmic elevation of the exterior.

Organised around a vast courtyard with an ablution fountain at its centre, the four-iwan plan accommodates madrasas for each Sunni school of law. The qibla iwan rises to commanding height, its scale reinforcing spatial hierarchy. Student cells are aligned along the outer walls—each window contributing to the rhythmic elevation of the exterior.

Al-Azhar Madrasa – Cairo, Egypt-bf47cc89-8bd6-44a9-8997-acc07b18ec97.jpg) Founded in 970 by the Fatimids, Al-Azhar began as a congregational mosque before evolving into one of the world’s oldest universities. The original hypostyle hall—supported by reused Roman columns and capped by domes at the mihrab and entrance—set the foundation for a millennium of continuous architectural layering.

Founded in 970 by the Fatimids, Al-Azhar began as a congregational mosque before evolving into one of the world’s oldest universities. The original hypostyle hall—supported by reused Roman columns and capped by domes at the mihrab and entrance—set the foundation for a millennium of continuous architectural layering.-0376049a-c1ca-4231-ac04-039ac88bd00f.jpg) Over centuries, Ayyubid, Mamluk, and Ottoman rulers expanded and adorned the complex. The Taybarsiyya and Aqbughawiyya madrasas introduced early Mamluk features such as keel arches, mosaic-inlaid mihrabs, and red-and-black marble portals. Later interventions by Sultan Qaytbay and ‘Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda integrated courtyards, gates, and minarets, weaving a physical record of Cairo’s changing dynasties.

Over centuries, Ayyubid, Mamluk, and Ottoman rulers expanded and adorned the complex. The Taybarsiyya and Aqbughawiyya madrasas introduced early Mamluk features such as keel arches, mosaic-inlaid mihrabs, and red-and-black marble portals. Later interventions by Sultan Qaytbay and ‘Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda integrated courtyards, gates, and minarets, weaving a physical record of Cairo’s changing dynasties.

Zaytuna Madrasa – Tunis, Tunisia-3f4691fe-53e8-4add-84e2-953e8bdbb07a.jpg) Anchoring the medina of Tunis, the Zaytuna Mosque and Madrasa trace their origins to the 8th century, rebuilt under the Aghlabids in the 9th. Its vast 5,400-square-metre plan centres on a courtyard (sahn) surrounded by arcaded galleries and a hypostyle prayer hall supported by over 160 columns—many repurposed from ancient Carthage.

Anchoring the medina of Tunis, the Zaytuna Mosque and Madrasa trace their origins to the 8th century, rebuilt under the Aghlabids in the 9th. Its vast 5,400-square-metre plan centres on a courtyard (sahn) surrounded by arcaded galleries and a hypostyle prayer hall supported by over 160 columns—many repurposed from ancient Carthage.-9b0d7c32-99e0-47bf-af3e-5b699d51c137.jpg) The mosque’s spatial geometry reveals subtle asymmetries: a slightly rotated qibla axis, a trapezoidal hall, and a T-shaped plan accentuated by domes at the entrance and mihrab. Each addition—Hafsid minarets, Fatimid cupolas, Ottoman marble surfaces—left traces of its era without erasing the original structure’s clarity.

The mosque’s spatial geometry reveals subtle asymmetries: a slightly rotated qibla axis, a trapezoidal hall, and a T-shaped plan accentuated by domes at the entrance and mihrab. Each addition—Hafsid minarets, Fatimid cupolas, Ottoman marble surfaces—left traces of its era without erasing the original structure’s clarity.-eb9377c9-347a-471c-803e-329827493332.jpg) As the heart of the surrounding souks and the adjacent Zaytuna University, the complex fuses urban and spiritual life, standing as one of North Africa’s most enduring monuments of Islamic architectural continuity.

As the heart of the surrounding souks and the adjacent Zaytuna University, the complex fuses urban and spiritual life, standing as one of North Africa’s most enduring monuments of Islamic architectural continuity.

Char Minar Madrasa – Hyderabad, India-1ebea00d-2104-444f-958a-401745980e19.jpg) At the centre of Hyderabad, the Char Minar (1591) redefines the madrasa typology into an urban monument. Commissioned by Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, the structure rises 55 metres at the crossroads of four grand avenues—a fusion of ceremonial gateway and elevated mosque.

At the centre of Hyderabad, the Char Minar (1591) redefines the madrasa typology into an urban monument. Commissioned by Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, the structure rises 55 metres at the crossroads of four grand avenues—a fusion of ceremonial gateway and elevated mosque.-79270371-cd78-46b5-ad84-b6ffebfde16a.jpg) Its composition—four monumental arches supporting minarets crowned with domed pavilions—creates a geometric order that anchors the surrounding city plan. The mosque above the central chamber introduces a sense of layered sacredness, while the arches below operate as thresholds of movement and exchange.

Its composition—four monumental arches supporting minarets crowned with domed pavilions—creates a geometric order that anchors the surrounding city plan. The mosque above the central chamber introduces a sense of layered sacredness, while the arches below operate as thresholds of movement and exchange.-5e9acf82-1753-439d-9063-3dc74f8fec75.jpg) The Char Minar’s form resonated beyond India, inspiring later reinterpretations such as the Chor Minor Madrasa in Bukhara. In its synthesis of religious function and urban symbolism, it remains one of the subcontinent’s most distinctive architectural statements.

The Char Minar’s form resonated beyond India, inspiring later reinterpretations such as the Chor Minor Madrasa in Bukhara. In its synthesis of religious function and urban symbolism, it remains one of the subcontinent’s most distinctive architectural statements.

- Previous Article The SceneStyled Red Carpet Edit

- Next Article NEW IN: Dancer & Model Nada Abadir Launches Nuu Studio in Cairo

Trending This Week

-

Feb 16, 2026