SceneNoise x Hiya Dialogues: Kamilya Jubran

Lebanese journalist and founder of Hiya Shirine Saad speaks to Jubran about her upbringing, and how her time with Sabreen and experimental musicians around the world shaped her musical identity.

Interview conducted by Shirine Saad

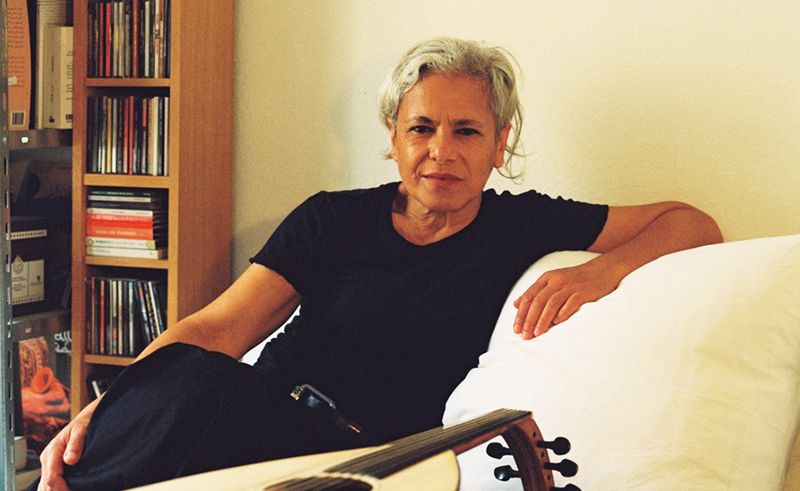

Born in Al Rameh, a village in northern occupied Palestine in Galilee, Kamilya Jubran is a composer, singer and oud player who has become one of the leading figures in the experimental Arabic music scene.

Growing up in a musically-inclined household, with her father working as a music teacher, Jubran was exposed to a rich repertoire of classical Arabic music like Umm Kulthum at a young age. She was so deeply immersed in these classics that making music ended up becoming a rather organic process for her. However, rather than following suit with the same school of her upbringing, Jubran created her own musical language and joined the iconic collective Sabreen, an avant-garde project from Jerusalem. She spent 20 years with them, exploring the intersection of Arabic folklore, jazz and contemporary music.

Personal and political, traditional yet forward-thinking, Jubran’s music boldly breaks away from the rigid confines of classical singing and composition methods, experimenting with new ways to use texts in music in fluid movements between tradition and modernity. She’s constantly reinventing her sound, redefining musical boundaries, and crafting dialogues between past, present and future, opening doors for many musicians and singers to reconsider and expand their creativity.

In this new episode of SceneNoise x Hiya dialogues, Lebanese journalist and DJ Shirine Saad speaks with Kamilya about her classical musical upbringing, Umm Kultum and how her time with the Sabreen collective and experimental musicians around the world helped her discover her own sound.

SceneNoise x Hiya Dialogues is a series conducted by Shirine Saad, highlighting radical feminist voices and influential artists from the SWANA underground scene who are actively engaging with historical revolutionary movements to challenge the cis-heteropatriarchal and capitalist structures within the industry through their art, music and poetry.

Looking at the situation now in Palestine, it’s really horrifying. Do you feel powerless or are you feeling that in your work, for example, you’re able to continue to resist?

I was not born on the 7th of October, 2023. I was born a little bit before, a Palestinian born in Israel in 1963. Through my long years in Palestine and then the last of course 20 years in Europe, when I decided to move or change a physical address, I never saw any glimpse of a better situation. Of course, recently it’s just getting worse. But, this doesn’t mean that we or the situation was better before, it was maybe a time bomb. We might go back to how it was before. I don’t really feel optimistic. But, the Palestinian resistance and the resistance of those who support Palestine give me much hope.

How about your practice at the moment, do you feel creative? Are you writing, reading or listening to music - what helps you sort of get through these times?

I go on doing more or less what I think I have to do, or what I think makes me feel alive. I wish every day to wake up and have a few little pieces in my brain that will help me think of how to continue making music. This is my only obsession at the moment, figuring things out. Because music is my life. It’s not work for me.

But, I really feel more and more challenged now, because in my music I never express myself according to certain political events. I focus my thinking on musical expression. I create music because I think there are so many things to do in the sphere where I choose myself to be, knowing that we can’t do everything we wish to do. So, I decided to be just very focused on what I’m doing and the way I see music, the way I hear it, in the way I wish to hear it worldwide. And, whenever huge emotional and humanitarian events happen, of course, I’m paralysed like everybody else in the world. So yeah, I’m there right now.

Through any kind of language, whether it is an artistic language or not, it’s really hard to make sense of this total genocide we’re witnessing It’s very hard to accept it as real. What are your thoughts about that?

I mean. There’s life, where we’re witnessing a lot of things, and then there’s art, and the question is, ‘Where is the line between both realities?’ And, though they are not very disconnected, it’s just a matter of the capacity of expression like, ‘Am I able to’, ‘Do I wish to do that or do I need time to absorb things?’, ‘Am I involved at all or do I want to be involved or not?’, ‘Are we all responsible, and in what way and what shall we do?’ These are really very diverse and big questions, and I think all of us are tormented by such questions.

And, at the moment, everybody is reacting the way they see is appropriate to them, where they feel they’re honest with themselves and where they see it’s important to do, and they are capable of doing it.

I wanted to ask you about your feminist and queer influences because I know you grew up in a musical Palestinian family, and I was wondering how your feminist awareness took shape growing up?

Actually, it’s funny you asked me about this question because, for me, it’s as if it was there all the time since I was, maybe, five or six years old. But, at the time, of course, we didn’t have this language, or this kind of awareness and those expressions. But, it didn’t matter to me. I was brought up in a patriarchal society under occupation, of course, this occupation and the system of colonisation were at the time very European, and are still in the Middle East right now, whether you want it or not. What I really wanted at the time as a kid, and then as a young lady and an adult, was mainly making the music that I wanted to create or leading the life I wanted. I was just looking forward to being 18 years old to get out of my parents’ house and live a life that any human being at the age of 18 deserves to have. No matter where the society is.

I didn’t think about that in the context of feminism or in terms of revolutions, I was just living what I believed in and that’s about it. I mean without big slogans, without big movements. I understand that we have to make movements, we have to make revindications and we have to call the things in their names, but maybe in my generation that wasn’t yet an issue in the place where I came from. Whereas if you look at the United States, maybe at the time they were much further in their struggle towards women’s rights, feminism, and so on. I never felt like I belonged there though and I never felt I was doing something different.

For you to pick up the Oud and the Qanun and to sing as a woman at the beginning; was it something that was easy? Was it supported by the people around you? And, did you feel really free on this path?

Well, I don’t want to sound like I was a spoiled kid. But, it was just a very natural thing to happen in our household. It just so happened that my father was fond of music, and my mother was too. My father was really a self-made man who decided to make music, and build instruments. So, I was born to a young couple who really struggled for their existence and had forbidden hobbies at the time - because at the time, they were forbidden hobbies. You’re living in occupied Palestine in 1948, you don’t have to think about art, you have to just think about being safe and not get killed or uprooted. They were lucky in that sense.

I grew up in this house where music was practiced every day, before meals, after meals, and if we didn’t have it every day, then there was something wrong. It was not a privilege, it was just something very natural that I grew up surrounded by instruments, and when I played them, it was the most organic thing to happen. There was never a discussion at home.

How about when you wanted to go out and perform in public - to begin to travel, as well? Did you feel supported? Was it something that you were able to do freely?

I did, actually. I can’t remember what kind of state of mind I had at the time when I was 18. I just saw that the sky was my limit and my parents never said anything about that. Of course, they may have wished for me to sing or become the person who just will sing this rich repertoire of Egyptian masterpieces. At the time, Umm Kulthum was the goddess at our home, and no other music was really appreciated at home besides hers. Also, the big masters of composition were basically of Egyptian origins, like Abdul Wahab and his counterparts. So, of course, my parents wished for me to become the person who would follow this line. And while I really loved that repertoire, at a certain point in time, when I was 14 or 15, I started to ask myself, okay, there are other things in the world that might interest me, not only that.

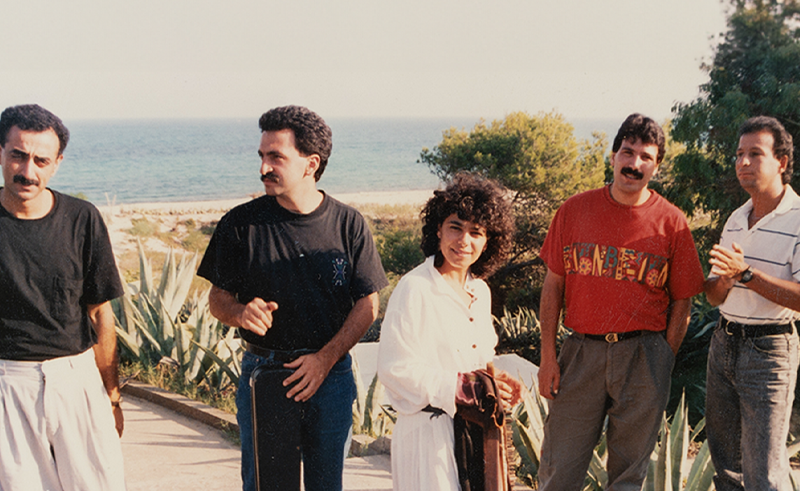

So, when I joined the Sabreen group in 1982 in Jerusalem and started to follow this way of thinking with the group, and this approach to creating and researching, the music was really strange for my parents. There was a big hiccup, like what are you doing? But, for me, it was just the right thing to do. And even at that moment, they were patient. Then they started to follow part of our concerts in Palestine at the time. They became fans, and I really appreciated that. My parents were simple people who didn’t go to universities and they don’t follow any kind of intellectual streams of thinking. It was just natural. It was not only them. Certain conditions allowed people to look at things in a calm way.

However, of course, the escalations changed afterwards. A lot of different political and economic pressures attacked Palestinian society, not only in Palestine but elsewhere as well. People became more and more stressed, so we started to be more cautious, afraid, worried and suspicious. I’m lucky to have lived this childhood, though it was really a childhood of war all the time. But, I don’t know what happened, or what really became more harsh since 1963 when I was born. Things changed and I think unfortunately everything changed around me. I don’t want to sound nostalgic, it still exists, but we have to just look around and see and analyse the positive things that are still happening. We have to stick to that and have faith in it, otherwise, what else?

When you said you were making music with the Sabreen group, trying to find a new sound. You kept saying, it felt right. What about that sound that made it feel like the right thing for you to be doing?

It relied on the ambitions of certain individuals, who once woke up and said ‘Who are we?’, ‘What are we doing and what for?’, and this is how any change or movement happens. Questioning is very important as it is the key to any changing movement, be it music, culture or whatever. But, it’s also a vicious cycle, because it’s enough for a person to have a model somewhere, whether something that they see in front of them or in history. And, at a certain point in our lives, we feel that we want to realise something and feel better. For me, I was brought up with classical Levantine and Egyptian music, and it was my daily food. So, at a certain time, I got fed up and then I said okay, I want something else.

At the time, during the 70s in the North of occupied Palestine, we started to hear songs of resistance which were interpreted by great musicians like Ziad Rahbani. And, locally, in Palestine, there were little timid temptations of groups of artists, which made me realise that there are alternatives to the classical repertoire. It made me think more and more about what I really wanted to sing at the time. With those questions, I moved to Jerusalem and I went to Hebrew University. I heard about Sabreen, and they were doing what I was already asking about at the time. They were just doing something that I personally wanted to do, but I never found the words to express it. It meant making the music that we thought should be done, and it was clear to me that this was the music school where I wanted to belong. At the time, I was studying something completely different in the university because studying music at the time for Palestinians was a big no, you didn’t have much of a choice regarding your studies. There were no conservatoires to teach Arabic music, and Israel didn’t allow us as Palestinians to do what we deserved to do.

So, the need was so urgent for me to look for the right sound and melody that made me feel okay and good in my skin. Also, being brought up in classical repertoire made me very selective about the quality of music I’m making, aesthetically. I didn’t want to make any cheap music or pop music for entertainment. Maybe it was a little bit odd, but I was looking for something to correspond with those values I was brought up on. But, at the same time, I was open to suggestions. I was open to the wave of protest songs and ‘El Oghnya l Moltazma’, a song that carried a certain level of engagement socially and politically, not only towards us as Palestinians but all of us Arabs because we’re all subjugated to the same misery but with different levels of tyranny and occupation.

But, musically I was really obsessed with the question of ‘What is that really I wanted to sing?’ At the age of 14 or 15, I sang the music that came into Palestine, produced and written by Arab artists who lived in Lebanon or in exile. And, for us Palestinians, this music was like a revolution – it was for us purely alternative music, the only music that everyone should sing.

With those practices in me, I can say why I was attracted to music such as Sabreen’s, the words, the different melodies and the different interpretations. I remember when we heard the music of Marcel Khalife, a singer who sings with the oud different melodies with modern texts that have really different political and humanitarian dimensions, especially the poems of Mahmoud Darwish. For me, that was a revelation. It was really cool. And, also hearing Ziad Rahbani sing about the Lebanese Civil War in a kind of sarcastic way showed me that there is a possibility that there are really things to do still and a lot of things that have not yet been done.

My meeting with Sabreen meant the same thing in Palestine. That chunk of time in my life made a lot of me and it still does, it opened up so many horizons for us in times when nobody showed us new horizons we had to make, build and breakthrough. I’m still to this day discovering new horizons, and Sabreen did that for, and still doing for younger generations living in Palestine who didn’t know who it was and discovering it now.

You mentioned that your parents felt that the music you were making with the group was a little strange, but then your music became even stranger –as you began to push the sounds and the lyrics even more. So, can you tell me about this creative process you had from the beginning until you’ve become more abstract with your own music?

When I joined Sabreen, I think I was the youngest in the group and I happened to be the only woman in a group of men. The leader of the group was more alert about the political situation in Palestine, and at the time I was so young and wasn’t educated enough politically. Being born in such a place doesn’t mean necessarily that you are aware of all the facts because there is continuous systematic oppression by the occupation power that tries to just erase the memories of the oppressed and brainwash them from being able to fight. So, working with the group helped me maintain all of the values from my musical upbringing at home, and also exposed me to a lot of music genres that I didn’t have at home or never heard of before. And, I was able to make a combination of both things.

Where I’m writing now is trying to find an answer to what values I really stick to and where I want to bring them today, to go further and develop.

Why did you want to make music that kept going stranger and stranger from the pop and shaabi songs that a lot of musicians now keep going back to?

It’s not a matter of being strange, I think it’s a matter of sounding a little bit too much different or unfamiliar. Culture is about real access to things and the manipulation of this access towards things makes us feel deprived of things. There have been so many fixated values forced on music that naturally it didn’t have. We categorized it and gave it a cultural and economic status and ruined it. We’re all living in that illusion that we have the right to listen to whatever but I mean for real we all don’t have the right to listen to whoever because music is manipulated and forced by so many powers. And, this is a really tough reality.

I was searching for a purer expression for my voice and I found a lot of that working with the Sabreen group. I believed in the vision the group carried at the time and it was great for me on a personal level. It felt so liberating in all aspects at the time, and with all those good feelings I had, I was greedy for more. And, then I moved to Europe and kept my research going on.

You said to Sabreen, that you discovered a liberation of feelings and sound. Did you get more liberation after your move and becoming a solo artist?

Yes, I felt more free doing things because only I would have to pay the price for the mistakes or whatever. I mean, the responsibility took another shape, it was really personal whatever I wanted to say, discover or experiment with. But, it also was like a double-edged sword. I started to compose myself for the first time when I was 39, I had just come to France with nothing and had to build myself from zero. It was quite the hassle that I had to handle but it was fine as long as things were working out for me musically. That really supported my legal situation in the country. I never felt that I had to do something else. I feel very fortunate and privileged in terms of being able to say what I want to say anytime.

You mentioned earlier the word experimentation, what that it mean to you, in terms of how you write, listen or collaborate with other artists?

For me, experimentation means, first of all, wanting more, and that need for more comes from being critical; to criticize the things that I have and that makes me want to try different things. It starts from there, and then the harder question comes, ‘What do I want or where do I go?’, and then comes the question of aesthetics. If I have a clear basic instinct of where my aesthetics allow me to go and in which corner to search, this is really crucial in finding the right threads that connect you to that world you are drawn to; to meet people who search for themselves and ask themselves questions about their own cultures.

I was lucky enough to meet such musicians in Switzerland and it helped me to feel that I am not alone and find a zone in which I want to learn, especially in contemporary music, electronic and jazz music. I found those certain areas very interesting and I managed to ask myself questions about my roots and where I could bring those roots to develop. It’s just as if you meet the right person, you find the area where you feel you are good.

What does the word ‘dissonance’ mean to you and what does it feel like?

Dissonance is the opposite of ‘harmony’ right? I think it is such a powerful essential part of music and we need it in everything.

Why?

Because otherwise, it’s boring. It’s flat. I think human beings are always in need of dissonance, otherwise, we just go home and die.

Don’t you think dissonance is a representational reflection of our reality?

When we have bombs, machinery and all that sorts of noise ruling our lives, especially in Palestine, while the music that’s being made is so melodic. It doesn’t really reflect the truth, no? You know the empty cup and the full cup. It’s a necessary part; the thing and its opposite. We need contradiction or life will be insufferable.

How are you able to function and be creative with the horrible things that are happening at the moment and the horrifying genocide we are witnessing? Are you able to be creative in the same way? And, does that change the way you look at your music and writing?

Yes and no. I mean no in the sense of the difference that we are living in today in comparison to previous times is the intensity and brutality that it’s happening in a very short period of time. But, the content itself is still the same as it’s been many years ago. It’s not something new for me, nor it’s quite today’s because everything has been talking about it since October 7th. So, in that sense, the pathway that I choose to be in –for many years now making music -has always been influenced by the background where I come from. A background of a little bit of history and a lot of a present and not much clear future. I think that played a role in shaping the way I look at music, and the music I wish to do.

So in that sense, things have not changed, I am just following the same line. Now, the intensity of the event right now could make me go down into a dark hole, so I have to pull myself up again. This could provoke certain words or sentences that I write in whatever creations I’m working on right now.

I want to shout and I want to breathe and that takes another shape in the music I’m making.

How so? And, also when you said a little bit of history, a lot of present and not much future, how does that sound musically for you?

Musically, I try to hold to my connections to the past, it’s not too far backwards because the references we have to that past we call ‘classical’ in the Middle East region, are not too old. I’m talking about the middle of the 19th century, this is not too much backwards. It’s not the Middle Ages. And, the present is what I try to modulate today and link to that past to express that cross-cultural life that I have been managing, and try to find a language that puts all of these elements together. And, there is not much of a future because our world is too saturated by so many sounds and sometimes I feel it’s nonsense what I’m doing.

We did everything and there are too many things happening and now we’re facing the artificial intelligence that will keep going over and moving faster and faster and probably erase whatever we know.

How do you compose? Do you hear sounds or words and how do you react to how you are feeling in your music?

This is very complicated to answer because of all of those emotions that accompany me when I see something in the paper or a recording, I don’t dictate them. They happen automatically and then the expression comes. When I compose, either there’s an idea that I’m working on or I am collaborating with someone on that particular idea and then musically speaking, I try to find a solution or a suggestion for that idea. So, we talk about combinations, melodies, rhythms, and sounds.

I think the fact that I’m more and more going towards improvised music in the European sense of the word, particularly around the end of 2022, is linked to the urge for immediate expression–putting the emotions first-hand and letting them go out before sitting and writing and thinking and trying to find complexity on a paper. At that point, emotions are guiding me, but still, I don’t know them until the expressions come out musically.

What do you mean by improvisation in the European sense? Because, of course, in Arab music, there was improvisation in classical music with moments of solos and so on.

Certainly, there are. What I meant is that improvised music became a genre in the Western world in comparison to written music. Those concepts don’t exactly apply to Middle Eastern music –yes, there’s an element of improvising that exists in our music but it doesn’t mean that we call this music improvised. There are rules that were set in order to talk about improvised music; we don’t call jazz music improvised even though that improvisation element is an essential part of that genre of music.

You’re the expert of Umm Kulthum –but she used to go on very long sort of flights in the middle of her shows that were so beautiful and drove the audience to a stance of trance or ecstasy even. How do you call these moments, where she was not even singing any words, she was just kind of improvising with her voice.

Improvisation. It’s simply improvisation. Like when any instrumentalist would play freely and we call it ‘Taqasem’ in Arabic. It’s the same when a singer improvises vocally, we call it ‘Taqasem Al Sawt’, meaning the improvisation done by the vocals.

Why do you think she was able to bring audiences to this trance-like state with her vocal improvisation?

Because, traditionally speaking, belonging to this culture of the Middle East, we know the importance of virtuosity in music, especially in traditional or classical music. That virtuosity is important and it’s a kind of an element that enables a level of excellence of the material you’re dealing with. So, the more you know, the more experienced you are, and the more free or able you’ll become in the improvisation when the right moment comes. And, I think Umm Kulthum was raised up to that culture and she was brought up with that way of thinking, and that made her such a master.

Do you think she was freer than most singers at the time and still is one of the freest in terms of interpretations, even in her life, she was able to embody such creativity and liberation.

Musically speaking, she had the mastery and she had the capacity vocally, and that makes her unique. And, these two elements didn’t exist in the musical careers of other singers at her time. And, her being surrounded by a group of composers and musicians who shared her background allowed such phenomena to happen.

Most of the songs during that era, whether the short 3-4 minute songs or the monologues-like ones, from Zakria Ahmed to Um Kultum, were composed in a certain structure, which is basically an idea of improvised melody –but it’s very stable more or less structured. To interoperate that type of music is a wholly difficult exercise to do. It’s because the composers themselves at that time were virtuosos and excellent improvisers that their compositions followed that sense. And, Umm Kulthum had the capacity to execute such a thing.

I understand that Umm Kulthum doesn’t have to be liked by everybody –but we have to listen to music that we don’t like, analyse them thoroughly and learn from them.

So returning to dissonance, because it’s not only the dissonance in the interpretation or the moments of free improvisation but also in the manner of performance, of living and the values you’re embodying as a woman –are you catering to patriarchal society and stepping in that seductive submissive role or are you in a dominate role?

First, the domination in a very patriarchal domain is the mastery of singing a style of singing that was basically initiated by men –so Umm Kulthum was better than them. She had the capacity to interpret that music which became a huge reference in the Arab singing style and vocalism. Nobody can ignore that phenomenon of Umm Kulthum because she was immediately qualified and with no discussion about whether we liked her strong position or the domination of her orchestra.

People usually associate a certain appearance –with all the hair and the makeup -with you being a woman Arab singer. But, you’ve cleared yourself from all of this. What does that mean for you and how do you do it?

When I want to talk about what I do, my reference in the aesthetics of music will go back to Umm Kulthum’s school, which is not her directly, but the people who came before her. And, that’s where I dig. Though they were men, it doesn’t mean I want to burn them because they were men –they created something amazing. Now, the way I look at that invention and the way I want to use it, I give myself all the freedom to do what I want to do.

You said that you are interested in the excess–what happens outside or between the rules or the notes, which creates moments of magic. Can elaborate more on these moments of flight of imagination?

It’s a matter of preoccupation probably. Umm Kulthum was preoccupied with what she was doing and that’s it. I think I’m preoccupied with other things these days, I don’t share in that sense of preoccupation of that period of time. And, that’s normal. We advance in time so we get interested in other questions that tackle the evolution of a certain tradition. And, I think I’m there at the moment, preoccupied by that notion or thought. What do we do with the education we receive and how we project to the future, is what I’m concerned about. And, I expressed it in my melodies in the latest creations I’m doing.

You’ve always been a revolutionary singer, whether under the occupation with your band or now on our own, are you taking that tradition of revolutionary music and exploring new ways of doing it?

I mean, when I started going in that direction, it wasn’t about me being interested in revolutionary music, it was about whatever I was feeling and what I liked to do at the time.

But, do you see your music as a weapon of resistance?

I wouldn’t use the word ‘weapon’. What I do is just probably a way of defending thoughts or a way of thinking or looking at things,

So tell me more about this way of thinking, especially in the context of living under the occupation all the time.

No matter what we do, living under the occupation, it doesn’t have to be revolutionary music, even if we are just baking our bread, no matter what we do –this is resistance in a sense. And, not only in Palestine but in any occupied society as well, the people who suffer from the regime of hegemony, resist every single morning. So, that’s one thing.

Creating music, of course, is not detached from that reality. It gives it a colour or energy and I’m very much aware of that. But, then at the end, it’s a personal journey of musical discovery.

And how do you express that personal journey? For you, it’s about moments of departure from the expectations of what you are supposed to do as a traditional Palestinian musician.

When I joined the Sabreen group, the music we created was so far away from being folklore or resistance songs that would talk directly about the Palestinian cause or the occupation. Instead, we focused on the music we wanted to create and that made sense for us at the time to do it. And, that some form of a new language –took some time for our audience to adapt to it. The material we created at that time was revolutionary in that sense.

When I’m thinking about that surge of pop music that’s coming out of the region, it doesn’t make me feel good –so, how do we approach that question of the new language, and who gets to decide what the normal language is and what is the new language is and how we respond?

I think it’s a master of accumulation of productions and classification. And, it’s a matter of being exposed or not being familiar with or not. It’s how we educate our ears mostly.

And, don’t you think we can practice a capacity for really listening and liberating? Sensorial liberation, right?

I think we’re able to learn all the time. It’s just a matter of wanting. But, the more we advance in time, the more it gets difficult to defend our creativity between brackets because we are so swamped with a lot of information all the time. So, we can easily lose the compass and our focus and in order to be able to maintain the lines, it’s a big battle that requires a lot of work. However, there is an advantage to that age as well, which we can find any information we can easily. So, it’s a double-edged sword. We advance, the price is very high and things need more effort but the world is much more open.

You sing in Arabic. How do you feel about people not understanding the words and the language of your music?

That question didn't only exist since I moved to Europe, but also when I toured with Sabreen to non-arab countries. So, at the time during the performances, I had to explain a little bit more about what the songs were talking about. Now, after I moved to Europe, the question became more insistent, and I had to find solutions –however, I’m still working on that - to communicate the content of what I’m saying. I tried subtitles, distributing papers and translations in QR codes, and sometimes both. But, there are so many ways to overcome that hurdle of communication. So far though, it works very well for me, sometimes even some of the audience would come to me and tell me that they don’t need to understand what I’m saying they can feel it. You do whatever you have to do because it’s a part of your job to communicate the message to the audience.

Are you ever scared of speaking your mind, making music and talking about Palestine?

No. I’m worried about the general situation of course, and the people who pay the price and I feel helpless. I’m privileged that I make music about it, and I feel ashamed. There’s nothing to compare.

But, don’t you think that making music has so much power?

I mean consciously I know that. And, all of us in that industry, know that it’s important to go on and do what everybody is doing. But, this goes in parallel with the daily pain and the sense of helplessness that you feel. I also feel that going on doing what we believe we need to do is the answer.

Watch the full interview below:

- Previous Article Kazdoura’s Debut Album ‘Ghoyoum’ is A Tribute to All Victims of War

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Mar 13, 2026

-

Mar 11, 2026