A Saudi Artist’s Excavation of an Understudied Hejaz

Sarah Al Abdali traces pigments and tombstones to recover the Hejaz, a place often visited but rarely seen, where kitchens, courtyards, and gravesites hold the memory that history overlooked.

The first time Sarah Al Abdali realised that the archive was looking back, she was standing amongst stones. At the Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah in 2023, her audio installation, 'After Hijrah', gave voice to historic tombstones from al-Ma‘la cemetery in Makkah, otherwise known as shawāhid, witnesses. Inscribed with names and genealogies, the exhibition ventured into a space long treated as taboo, excavating a death culture particular to the Hejaz that many would rather leave unspoken: tombstones and rituals of grave visitation that certain religious ideologies have discouraged, despite abundant historical evidence still waiting to be studied.

In the painstaking research that fed the work, she traced two markers to her own seventh- and eighth-great-grandmothers. “An interest in something made me realise maybe I was meant to do it,” she told SceneNowSaudi. The stones spoke of a culture long practiced, lately policed, and still understudied.

Sarah Mohanna Al Abdali is a Saudi multidisciplinary artist and one of the country’s first notable street artists, known for blending traditional Hejazi forms with contemporary critique. A graduate of Dar Al-Hekma University and The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts in London, she works across painting, illustration, ceramics and site-specific installation, often engaging with themes of heritage, loss and urban transformation in the Hejaz.

If the Hejaz is usually treated as a foregone conclusion, and while Makkah and Madinah are seen as global symbols rather than lived places, Al Abdali insists and bets on the region’s grain. “I had so many questions about individual and collective identity,” she said. “What does it mean to grow up in the shadow of the ḥaramayn, and how does that translate into a language of form?” The answers she offers are stubbornly material. A lattice shadow becomes a key compositional border. A tiled floor eats a room’s perspective. A plate rack is a thesis about domestic authority. The work aims to discover how that daily Hijazi life holds the authority of place.

Al Abdali grew up in Jeddah, in new houses that treated Western modernity and minimalism like a credential. Old architecture wasn’t something she grew up with in her childhood; rather, she was only able to approach it as a research project. “I lived a duality, people choosing new architecture to perform being modern.” When she later left for London to study Islamic arts and architecture, she specialised in Hejazi material culture and returned with what she calls “a bird’s-eye view of belonging and not belonging.” The region is at the spiritual centre of a faith, and yet its objects, its cupboards and sarai, its women’s quarters and small economies, were scarcely catalogued. “Even historians are still looking into these landscapes,” she said. “It has been understudied for so long.”

Her earliest work manifested in her street art, putting pictures where the city could answer back. “The street was my first thought,” she said. “Medium followed growth, not the other way around.” Al Abdali aims to inventory nostalgia her own way. You sense an artist suspicious of nostalgia’s narcotic. Nostalgia often smooths; her compositions snag. Even after she shifted from graffiti to gallery work, her pieces kept the same sense of public address, they still speak outward, even when displayed in private rooms. Critics have been quick to call her a pioneer; she is quicker to insist on method, fieldwork, archives, family memory, and an ethics of detail.

The Hejaz she paints is a system of rooms and responsibilities, often held by women whose names fall out of the grand accounts. In her 2019 exhibition 'The Simorgh Always Rises', miniatures breathed in domestic air: kitchens, courtyards, windows where neighbours lean into each other’s sentences. The title pointed to the many-in-one bird of Persian lore, but the argument was local and precise. The show includes works on paper and paintings of females, some of which were done in the style of Islamic manuscripts, painted in scenes of vernacular traditional home spaces inhabited by Saudi women. Al Abdali’s exhibition was presented in her grandfather’s historic home in Jeddah, Bait Al Sharbatli, whose traditional architectural features mirrored the scenes of Al Abdali’s works. She made space for the Tabariyyāt, women scholars who once resided in Makkah, and for the urban infrastructures they ran, the ribāṭs where charity and female administration were ordinary facts. The work returned these women and spaces to visibility, giving them back their rightful place in the story.

Al Abdali speaks of her materials as though they were mentors; inert tools but also guides, each with its own temperament and lesson, shaping the work as much as she does. In one drawing, gold alone - 12, 18, 24 karat - replaces colour so that the surface will oxidise and mellow, time slowly making its mark on the work. Elsewhere, she dyes paper with natural pigment to guarantee that change is baked in; charcoal and handmade colours temper the finish away from the sterile eternal. “I love using natural materials to portray decay,” she said. “To let the painting age with time and show its breath.”

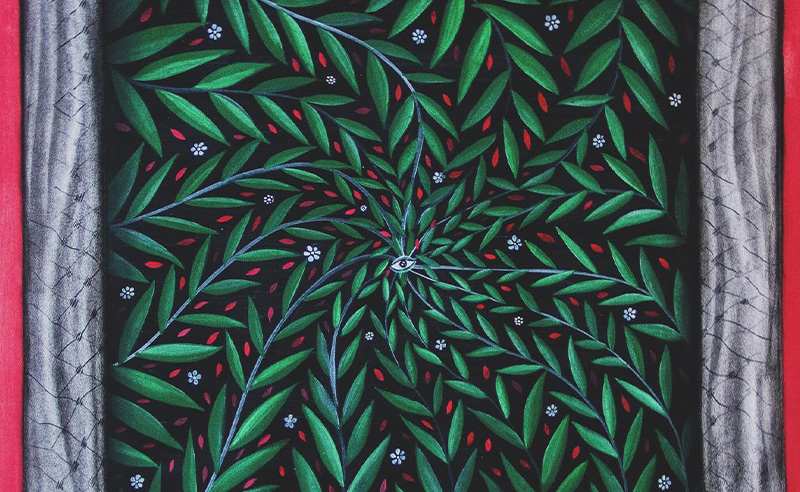

In 2024, Hafez Gallery mounted 'Growing Vines of Sodom', a show that looped grief and regeneration through a plant, Ushar, the Apple of Sodom, thick-skinned, toxic, thriving where tenderness fails. The compositions were meditations on endurance without piety: leaves that refuse allegory. The exhibition read as a private reckoning and a regional one; it asked whether survival is a moral category or just a fact of terrain.

Everything returns to the understudied: to the drawers and ledgers of a port city whose cosmopolitanism is often flattened into a tourism pitch, or into reverence so total it forgets to look. Al Abdali describes herself, first, as a researcher, helped along by a historian father. A piece will sit until she finds the object that persuades the room to listen: a tobacco tin, a cut of patterned cloth, the particular green of an enamel kettle that every aunt owned. “We keep very minor traditions,” she said, “and let so much else go.” Part of her project is to make those “minor” things legible again.

The tension between preservation and modernity is where she seems most at ease. She doesn’t preach against the new; she advocates for its frictions. Past and present sit together until the seam is visible. “I loved showing how the visuals and the actual materials carry burnout with time,” she said, describing a work in which the paper itself darkens as if from long handling. It’s a counter-proposal to the antiseptic future once promised by glass towers; here, modern life is allowed to scuff.

There is a story Al Abdali tells near the end of our conversation, a scent-memory from her grandmother’s kitchen: glasses perfumed before guests arrived. It surfaces again in her recent writing, a novel titled 'رحيل في أعماق المدينة' ('Departure in the Depths of Madinah'), and it lands in the paintings. Perfume a glass, not the whole room. Start at the mouth of an object and move outward. That is how a region really becomes legible.

Trending This Week

-

Feb 16, 2026