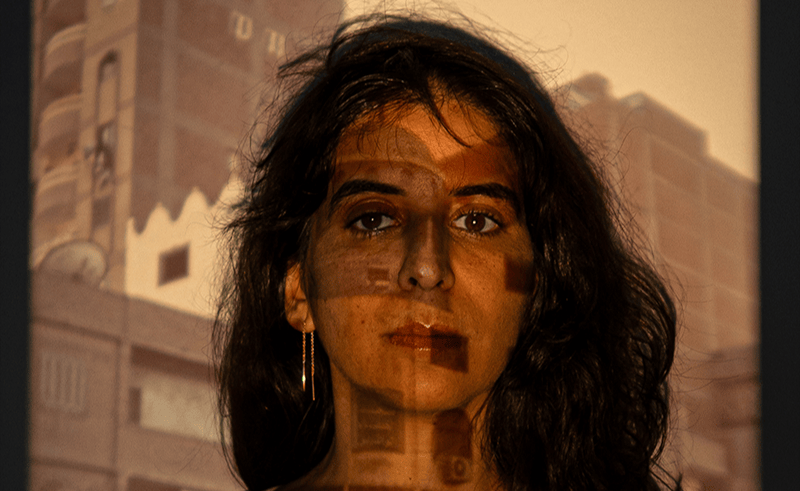

Artist Manar Moursi Examines Authority Along Cairo's Ring Road

Combining a decade of research and multimedia art, Moursi's latest exhibition is a deeply layered exploration of authority and authorship along Cairo's growing edges.

Stepping into Manar Moursi’s latest exhibition, a latent, collective memory is re-activated. In near darkness, a metal structure resembling a minaret charges the space around it with blue and green LED light. You have seen such a structure before, along the highways of Cairo and the Delta, late at night, looking out the window of a car or bus. Moursi’s multimedia exhibition, The Loudspeaker and the Tower, attempts to assign meaning to it.

Born from a decade-long research project, Moursi’s exhibition examines authority and authorship along Cairo’s expanding edges, where community-funded mosques and their neon-lit minarets—the inspiration behind the project—are a common sight. The exhibition combines both the artistic intuition and scholarly rigour of Moursi, an Egyptian-Canadian academic and artist whose PhD research at MIT intersects art and architecture, and whose previous work has been exhibited across the Middle East, North America, and Europe.

First exhibited in 2019 in Toronto, The Loudspeaker and the Tower was brought home to Cairo at the tail end of 2025 in an exhibition held at Garden City’s ARD Art Institution. In a written conversation that spanned weeks, Moursi spoke with us about how this exhibition came to be, and how the intertwined experiences of scholarly research and art fed one another to give birth to a work as deeply layered as The Loudspeaker and the Tower.

First, can you tell us how this exhibition fits within your broader body of work?

The exhibition continued my long-standing interest in how architecture, infrastructure, and sound shape us socially, and shape our beliefs. It marked a shift in how my research is articulated, rather than a departure from the object of the research itself.

At the same time, while public space remains central to both my research and the exhibition, the exhibition turns toward domestic space, allowing me to explore how larger political and social structures are carried into private interiors.

Clearly, it was also a very collaborative process, which isn’t always visibly the case in academic research.

Because the work is concerned with how space, voice, and power are collectively produced and felt, collaboration became a necessary method rather than a supplementary gesture. The exhibition was shaped through many interviews as well as collaborations with sound designers and artisans. These processes allowed research to emerge through encounter rather than from a single authorial position.

Where was the starting point?

This project had several intertwined starting points.

One starting point was a visual fascination with the sculptural presence of illuminated minarets at night. That fascination was sharpened through my encounters with moulids around 2010, when I began attending them more frequently. Traveling back to Cairo from these moulids after dark, illuminated minarets emerged as points of orientation and intensity within otherwise dark landscapes.

Another starting point was a desire to document and understand the typological diversity of minarets that has emerged over time. Cairo is famously described as the “city of a thousand minarets,” yet today that number has expanded into the tens, if not hundreds, of thousands. While there is extensive scholarship on Mamluk, Fatimid Islamic architecture, there is relatively little research on Cairo’s modern and contemporary mosque architecture. This project became a way to study the form and function of these newer religious structures and to think through their social, political, and urban implications.

The project also began at a moment of personal transition. I was moving away from Cairo to live more permanently abroad, and the project became a way for me to encounter the city beyond what was familiar and ultimately understand my own relationship to it. The components of the exhibition comprise very diverse mediums, from installation art to photography, documentary film, and audio recordings. Was that planned from the start?

The components of the exhibition comprise very diverse mediums, from installation art to photography, documentary film, and audio recordings. Was that planned from the start?

The project began with photographic documentation of illuminated minarets at night. Over time, this expanded into daytime photography and interviews, as I became more interested in how these structures were built, used, and how authority and voice circulate through them.

This research eventually led to the video work Stairway to Heaven, a film which moves through construction sites, taxi backseats, and half-finished mosques to assemble a polyphonic account of voice, censorship, and access to resources in the city.

From there, the project continued to grow into sculptural installations and writing, as I searched for ways to create more spatial and embodied experiences with light and sound that images and interviews alone could not hold. The writing gradually became more personal, leading to the video essay Letters from Distant Orbits, addressed to my late mother.

One of the people who stood out most to me in Stairway to Heaven is the man who talks about building a mosque on the same plot of land as a church, as though in rivalry with it. Can you tell me more about that man and the mosque?

That mosque had stood out to me long before I met him. It is a massive structure, around ten to twelve stories high, sitting directly along the Ring Road. Despite its scale, it often appeared vacant or unfinished, yet it was unmistakably marked as a mosque through its minarets. What made it even more striking was its immediate proximity to a church, a pairing that is not unusual in Egypt, where mosques and churches are often built side by side, but which in this case was amplified by the sheer size and visibility of both buildings.

When I finally spoke with the man who had overseen the mosque’s construction, what stayed with me was the tone of his account. He explained the process in a practical, almost matter of fact way, without framing it in overtly political terms. He described how the mosque began as a tent, then slowly rose floor by floor as money became available. He also recounted how the decision to keep building upward was shaped by the church next door. As the church grew taller, the mosque did as well, almost in parallel.

The man was not explicitly speaking about politics, yet his account revealed how religious architecture becomes a site where power, competition, care, and surveillance quietly intersect. The mosque’s restricted opening hours, the security regulations around prayer, and the contrast between its monumental scale and limited daily use all pointed to a gap between what is built, what is allowed, and who ultimately has access.

That encounter crystallized something central to Stairway to Heaven, that large political questions are often lived and articulated through everyday language rather than ideology. You first exhibited The Loudspeaker and the Tower in Toronto in 2019. Why Toronto, and what made you bring it back to Cairo? How did the reception change?

You first exhibited The Loudspeaker and the Tower in Toronto in 2019. Why Toronto, and what made you bring it back to Cairo? How did the reception change?

At the time, I was living and teaching architecture in Toronto, but I always knew that I wanted to bring the project back to Cairo.

The reception differed in meaningful ways. In Toronto, audiences often engaged the work through feminist frameworks and questions related to urbanism, land use, speculation, and access to services.

In Cairo, the addition of new works, particularly Letters from Distant Orbits, and the accompanying public programming created space for a more intimate and reflective engagement shaped by shared cultural reference points. Many viewers connected personally to the work through questions of grief, loss, and how transformations in the city echo losses in private life, such as the death of a parent or the disappearance of familiar places.

Artwork typically serves as its own context, but you accompanied the exhibition with a public programme which included an artist walkthrough among other things. Can you tell us about your intention here?

In both Toronto and Cairo, the exhibition was accompanied by a workshop that I co-mediated with a poet and a sonic artist. In Cairo, this took place with Farida Gohar and Hoda Marwan. The workshop invited participants to reflect on their memories of public places in the city through collage writing and sound-based practices. The responses felt like an extension of the exhibition itself, as they translated its questions into lived language.

These moments of collective making and discussion, as we produced and edited the texts and sound pieces together, sharpened my understanding of the work by showing how its themes are activated differently when people are invited to respond creatively rather than analytically. The workshop revealed how questions of displacement, access, and change become legible through small, personal details, and affirmed the project’s ability to hold both collective conditions and deeply individual experience at the same time.

And, more broadly, what have you taken away from the process of bringing such an exhibition to life?

I learned that research driven projects need time to breathe and transform. Some questions can only be answered through sustained engagement, repetition, and return. I also learned to trust shifts in form and to allow a project to move from documentation to reflection, and from analysis to vulnerability, without seeing that as a loss of rigor.

I also learned how demanding it is to bring such projects into being, and how deeply they rely on care, patience, and collective effort. The work could not have existed without the time, trust, and generosity of the people who shared their stories, voices, labour, and attention, or without the collaborators who helped carry it across different cities and moments. This process made clear that research is not only an intellectual practice but a relational one, shaped by listening, responsibility, and the slow work of building community.

In that sense, the project taught me that rigor is sustained not only through method and analysis, but through commitment, care, and the relationships that allow a work to keep unfolding over time.

Finally, what can we expect from your coming work?

I am interested in continuing to work at the intersection of sound, infrastructure, and autobiography, particularly through long form video essays and writing. I want to further explore how personal narrative can coexist with research-based practice, and how intimacy can function as a method rather than a retreat from politics.

I am also currently developing the writing in Letters from Distant Orbits further to accompany the images in a forthcoming book titled Storm Over Cairo, planned for publication later this year.

Photo credit: Mark Onsi & Manar Moursi.