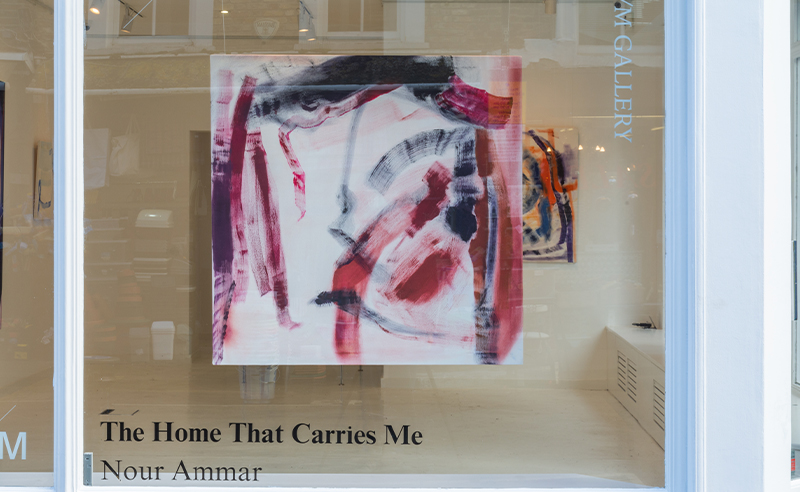

How Egyptian Artist Nour Ammar Found Liberation in Abstraction

The painter questions what makes a home a home and what makes a painting a painting.

To many people, the broad category of “abstract” art is difficult to understand, let alone relate to - let alone, as an artist, chart. When a painting’s structure is not immediately clear, most of us find it difficult to allocate any emotion, or meaning, to it. When I perused Arab art collective Hayaty Diaries’ latest exhibition, a solo show by Egyptian painter Nour Ammar, I felt the same way - the paintings seemed to say something I couldn’t really grasp.

When I reached out to Ammar in an effort to understand what kept me from grasping her art, I found out that the artist herself initially struggled to understand the art form. Despite having involved herself in making art very early in life - about as early as when she was learning to walk - and studying visual art in Toronto and Milan, the artist still perceived a disconnect between herself and the art form, until last year.

In the final year studying for her bachelor's, Ammar invested her time in untethering herself from her previous notions of what painting was. She moved into a flat in Milan, and set out to both learn and unlearn. “I felt like I needed to take as much advantage of my time in Italy as possible,” Ammar tells CairoScene. “So I turned into a sponge and absorbed everything I could, from both my surroundings and my mentors.”

In this newfound openness, Ammar found herself drawn to commitment - one that took her into her studio even when she didn’t want to and to find her emotions even when they tried to hide. In front of her canvas, or perhaps on it, she got to understand parts of herself she never thought she would. “Throughout this year, I realised that I needed to take my focus away from the outcome of what I was painting, because it’s not crucial to the process or the journey,” Ammar says. “I think this very uncertainty is what allowed for parts of myself to emerge through the work. For me to articulate honestly, experimentation has to overpower comfort.”

Throughout that year, Ammar found herself flung into the middle of an existential crisis (well, the good kind) that necessitated that she redefine her life in terms of her art. As she gained a more thorough understanding of herself, she was able to exit the cognitive box of art she had unknowingly put herself in. “I got to be where I am now by being more in touch with my instincts - by listening to my intuition more closely. It was less about my paintings changing alone, but more about me becoming more in touch with what painting is to me. I had to listen to myself even when it was scary.”

As she listened more deeply to herself, Ammar began to loosen the definition of a proper “painting” in mind, which allowed her to not only understand the world of abstract art, but to also be engulfed in it. “It takes a lot of practice to escape the idea that a painting should look a certain way. I used to believe that the gestures of abstract painting were the result of random mark-making, a desensitised art form with no sense of structure or gravity. But when I started painting more intuitively, I understood that the movements are not random, they’re weighted with emotion.”

This newfound enlightenment liberated the artist. She could create freely, knowing that her art was rooted somewhere real. “It was liberating to know that what I paint is real. It’s liberating to be able to capture and analyse an emotion. After painting, it almost feels like it’s been released. It’s liberating to know that it can be understood by anybody who’s willing to look at it.”

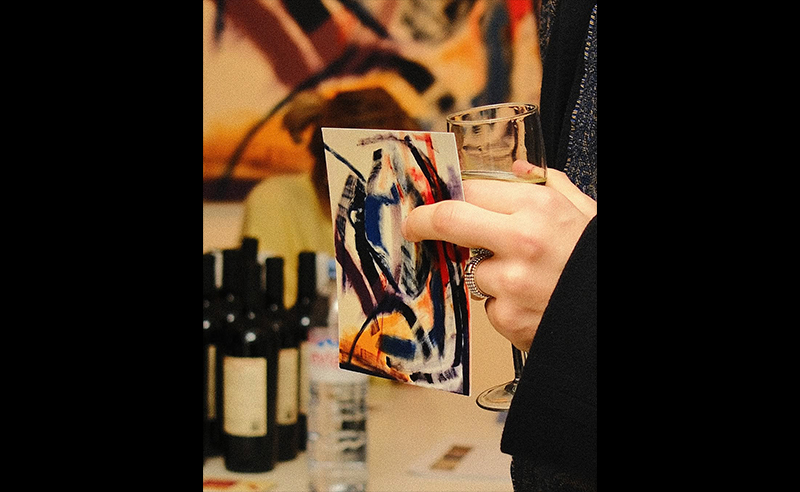

At the end of her year in Milan, Ammar had amassed a body of work that captured her internal transformation on canvas and made up her first solo exhibition, ‘The Home That Carries Me’. That name meant different things to different people - some people thought it was about her art, how that carried her throughout her life. When I first approached this article, I assumed her home was colour, that she took refuge in that in her time living in diaspora. In a way, we were both right and wrong.

“On my last week in Milan, I looked up at the ceiling of my Milan flat. “It wasn't an important ceiling to me but to look at that space and the experiences I had and the emotions I felt under it - that home literally carried me. I got to thinking about that feeling of being carried. My body is a home that carries me, my self, my paintings, my emotions, my energy. Throughout every phase in my life, something has carried me.”

As Ammar’s home changes and renews around her (or as she changes it herself - it’s a muddly two-way street), her art is constantly in motion. “Even if I paint a certain way, there’s a sense of comfort in knowing that the next one will be completely different. There’s no start and no finish. There’s no painting that would make me feel like I’ve finally reached the end of my potential. I think it’s a beautiful thing that it just evolves and there’s no end goal. It’s just me versus myself and me versus the work.”