How Eight Displaced Palestinians are Rebuilding Their Lives in Cairo

We spoke to eight Gazans in Cairo about their stories, skills and shared desire for self-sufficiency despite displacement.

Originally Published August 9th, 2024

According to the Egyptian Embassy to the Palestinian Authority, there are more than 115,000 Gazan refugees in Egypt after over ten months of unprecedented Israeli aggression since October 7th, with the vast majority of them having landed in Cairo. Thrown into this unfamiliar megacity and forced to find an avenue for survival, rebuilding life here has been costly for Palestinians in more ways than one.

Having only established themselves professionally in Gaza, many newcomers with non-corporate skills are working jobs they are overqualified for, since every job is a lifeline. Artists, especially, are struggling to make a living amid a Cairene creative scene that is already oversaturated with talent.

What is more, pro-Palestinian activists, in Egypt and abroad, seem to be experiencing a paralysing sense of despair after watching ten months of broadcast brutality. International supporters of Palestine are often limited to vocal solidarity, volunteer work, and donating to charities, but Egyptians with the privilege of being in Cairo are in a unique position.

In proximity to so many displaced Gazans, they have the ability to support them not only personally, but professionally. Cairenes can hire Palestinians as freelancers, attend performances by Palestinian musicians, and visit Palestinian art exhibitions, all in their own city. Cairenes can engage with Palestinians here as people, and as professionals.

In light of this overlooked privilege of proximity, we spoke to eight Gazans living in Cairo about their stories, their skills, and their shared desire for self-sufficiency despite displacement. The violence has brought with it tangible loss - people, places and belongings - but also immense intangible loss - purpose, creativity and precious autonomy - which all too often goes unnoticed.

Omar Shalayel, Digital Artist:

Omar arrived at Beanos with his little brother Abdulrahmane in tow, who occasionally smiled shyly at me throughout the evening, with slightly more enthusiasm every time. Omar told me it was his 15th birthday that day, but Abdulrahmane did not complain once that I was occupying his big brother’s time on his special day. Rather, he sat quietly with his iPad and his book, and let Omar tell me all about his life as a graphic designer turned digital artist in Gaza.

Omar and his family arrived in Cairo on February 10th after evacuating four times, displaced from North Gaza to Rafah. “I feel I should learn new words to describe what we went through,” Omar mumbled as he struggled to vocalise his experiences. I could see him making internal decisions about what to say next, about what might be too much for me to hear, or too much for him to explain.

He detailed how his neighbourhood was always the first Israeli target in Gaza whenever there was an escalation, so his family were somewhat used to airstrikes. “There is a mosque, a police station, and a political training ground, all very close to our building.” But this time was worse than ever before. They fled to a hotel further from those key targets, but the force and volume of the bombs dropping in the area was astounding. Omar described the sheer power of the strikes to me, saying, “We could see the shockwaves from the bombings rippling across the walls.”

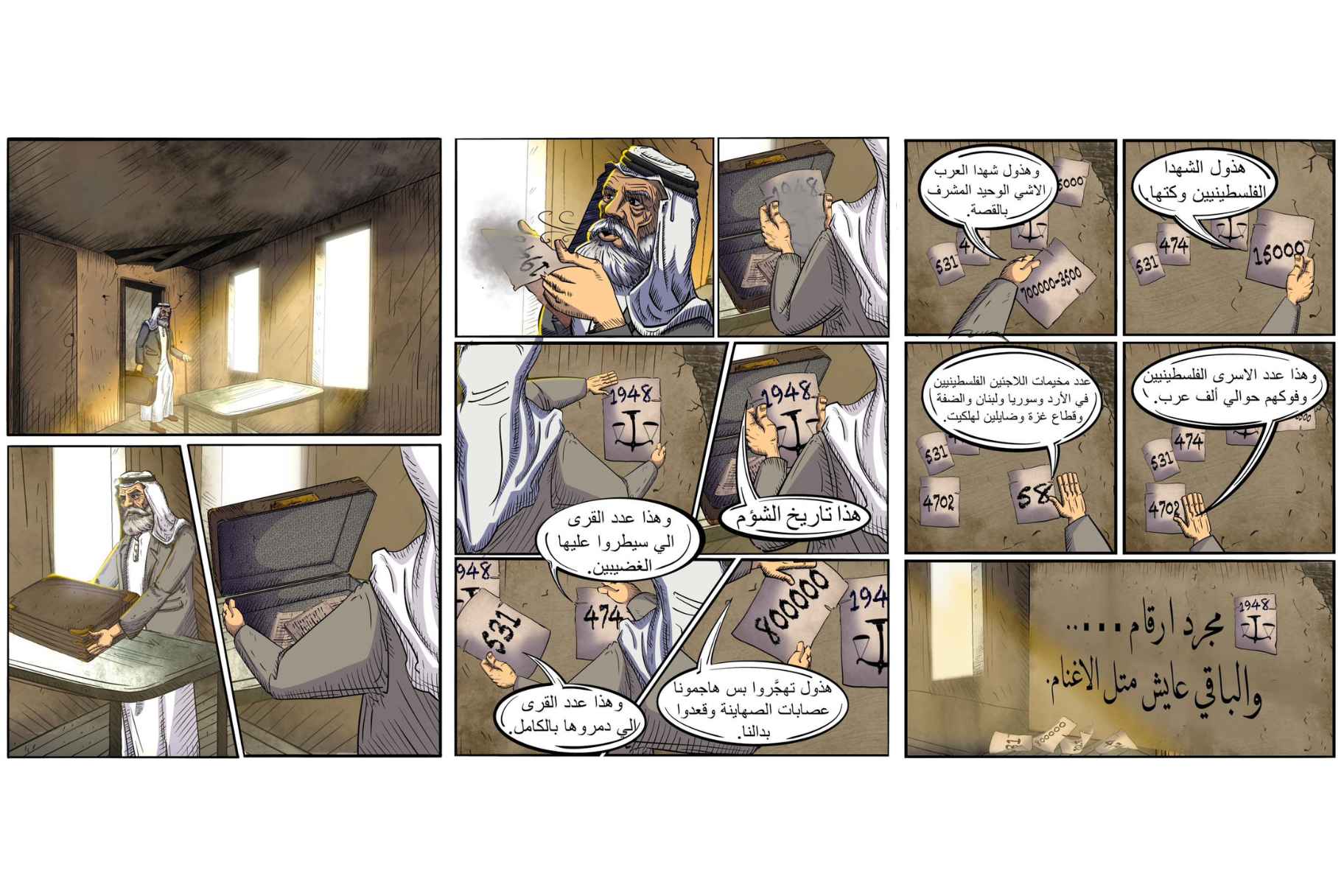

After starting out painting large-scale murals about seven years ago, Omar got into graphic design as a more financially stable mode of artistry. “Being an artist in Gaza is difficult, because the economy is not great,” Omar said. “People don’t have the money to support us, so art is not super respected.” But after two years, Omar grew tired of abrasive clients and laborious redesigns. When a friend offered him an opportunity as a digital artist at their new media company, he took it. Together they designed an original satirical cartoon, and even though the company founders eventually split up, Omar continued to work as a freelance digital artist.

Once he had found his calling, Omar made a name for himself within his community and across Palestine. His comic art was featured in an exhibition in Ramallah in May 2023, but he couldn’t physically attend because Israeli authorities denied him the necessary travel permit to leave Gaza. He worked for six long months to open up his own studio, and finally celebrated the grand opening on October 4th, 2023. “Honestly, life was good. It was the best it had been for the last two years. We felt like we had a future,” he said, even if that future could only exist inside the fences of Gaza.

Once he had found his calling, Omar made a name for himself within his community and across Palestine. His comic art was featured in an exhibition in Ramallah in May 2023, but he couldn’t physically attend because Israeli authorities denied him the necessary travel permit to leave Gaza. He worked for six long months to open up his own studio, and finally celebrated the grand opening on October 4th, 2023. “Honestly, life was good. It was the best it had been for the last two years. We felt like we had a future,” he said, even if that future could only exist inside the fences of Gaza.

He was hanging out with his friends on the night of October 6th, thinking of names for his art studio - ‘Obsidian’ was thrown around - and discussing the idea of making a short film about Gaza to participate in film festivals. “I’ll never forget,” he told me quietly. “My friend Mohammed turned to us and said ‘Guys, I had a dream last night that we’ll wake up tomorrow in the middle of the worst war we’ve ever seen’.” The little hairs on my forearms stood on end at that admission, and Omar continued his story. “He was right, and this all still feels like a dream I haven’t woken up from.”

Shahd Al-Shamali, Multimedia Artist & Mohammed Zohud, Musician:

Omar’s artist friends, Shahd and Zohud, arrived to join us an hour or so later, with similarly horrifying stories to share. Shahd’s family have been twice displaced, from Jaffa to Gaza in 1948, and again from Gaza to Cairo in 2024, making her a two-time refugee by blood. Shahd lost 22 relatives on her mother’s side in one bombing, and yet, as she put it, “We are the best-case scenarios. Because we are here, and we are alive.” Like Omar, she arrived in Cairo with her father in February, and her mother and little brother, a talented rapper, followed a week later.

Shahd, like Omar, is a visual artist, but also a self-taught painter and poet. She is currently working on a number of evocative comic stories and oil paintings, and was featured in an art exhibition in Treviso, Italy entitled ‘Out of Place’ from March to June, 2024. The exhibit showcased the artwork of over 160 global refugees, telling the stories of multiple cases of forced displacement through multiple mediums. She is also participating in an ongoing concept exhibition in Berlin called ‘The Terminal’, at which entrants are required to hand in their passports and go through a simulated checkpoint experience before they can view the artwork.

Despite her talent in drawing and painting, when I saw her again at a fundraising event for Gaza, she told me that she was thinking about getting into filmmaking because she feels that sometimes her mind works faster than her pen can. Soft-spoken but soberingly quick-minded, Shahd explained, “I struggle now to hold one idea in my head and express it slowly by hand, like I have to with my oil painting or charcoal drawing.” With one comic strip, she can present multiple scenes at speed, which she is finding cathartic at the moment with so many fragmented memories and ideas.

Besides being a multi-talented artist, Shahd is Zohud’s biggest fan. Zohud is a musician, singer and producer, who mastered numerous musical instruments at the age of 15, like the guitar, drums and piano, by watching YouTube videos. He started pursuing music seriously in 2012, and was a member of the first rock band in Gaza, named ‘Khata Matbaeiun’, or ‘Typo’. After releasing his first single in 2015, entitled ‘Ehlam El Nour’, he then produced an album by the same name, consisting of eight tracks about the beauty and the complexity of life in Gaza.

I was proud to watch Zohud perform alongside Saint Levant and Shahd’s brother, Ahmed, at the Deira Listening Party at the Citadel Central in July. His voice was smooth and strong, a keffiyeh tied to the microphone stand, and I watched the people seated around me jolt with surprise and delight when he began his set, the first performer of the evening.

After arriving in March, that concert was a triumphant moment for Zohud - but the struggles of being a displaced artist did not disappear overnight. “I am searching for bookings,” he told me, “but I lost all my instruments and amps in Gaza. Now I have to rent them for events, and I have nothing to practise with.” He told me about how he used to have a guitar in every corner of his home in Gaza, so that whenever an idea came to him, an instrument was on hand to have it realised.

Just as Omar had confided in me earlier, Zohud relayed how life for him, too, was just getting good in October of 2023. “All of us, me and Shahd and Omar, we had just gotten our names established as artists in Gaza.” In this new city, thrown into this new community twenty times larger than that of Gaza, it has been exceptionally hard for Palestinian creatives to break into the Cairo scene without help.

For those who have not heard him perform yet, Zohud will be playing at Darb 15 in Maadi on August 10th. You can contact Darb 15 via Instagram @d.a.r.b.15 for more information.

Nour Arafat, member of the Matbakh Beat Setty Restaurant team:

Nour Arafat was in fact the first person I interviewed for this piece. I was nervous, but she couldn’t see my jitters because we chatted on the phone, camera off. We quickly found common ground in our shared history of working at a family business, and giggled together about the trials and tribulations of running a business with your relatives.

Nour only lived in Gaza until she was eight years old, but she still talks about it like home, even though she has lived in Cairo for most of her life. She remembers Gaza especially for how beautiful and clean it was. “Everyone knows everyone there,” Nour told me. “As a child, everyone was my friend, and I was a guest in everybody’s house.”

Her uncle Sohail, with help from Nour and her extended family, runs an online Palestinian kitchen in Cairo called Matbakh Beat Setty. Soheil, his wife and his daughter arrived in Cairo from Gaza in December. His family was displaced very early on, after their house was bombed in the first week of Israeli aggression. His two sons were already in Cairo attending university, so he travelled with his wife and daughter only, but it was still “extremely financially draining,” Nour explained. “They were preparing to choose who would go first, but luckily they managed to get out all together… but it was hellish.”

Sohail did not want to leave Gaza, but after weeks of convincing from Nour’s father, he made the arduous journey to Egypt. He was a professional chef in Palestine, with more than one culinary accolade to his name. He ran a cafe that served drinks and shisha, managed a high-class hotel kitchen, training all the chefs and waiters, and even managed another beachside restaurant. “He was very good at what he did,” Nour beamed through the phone. “He really learned what worked over the years.”

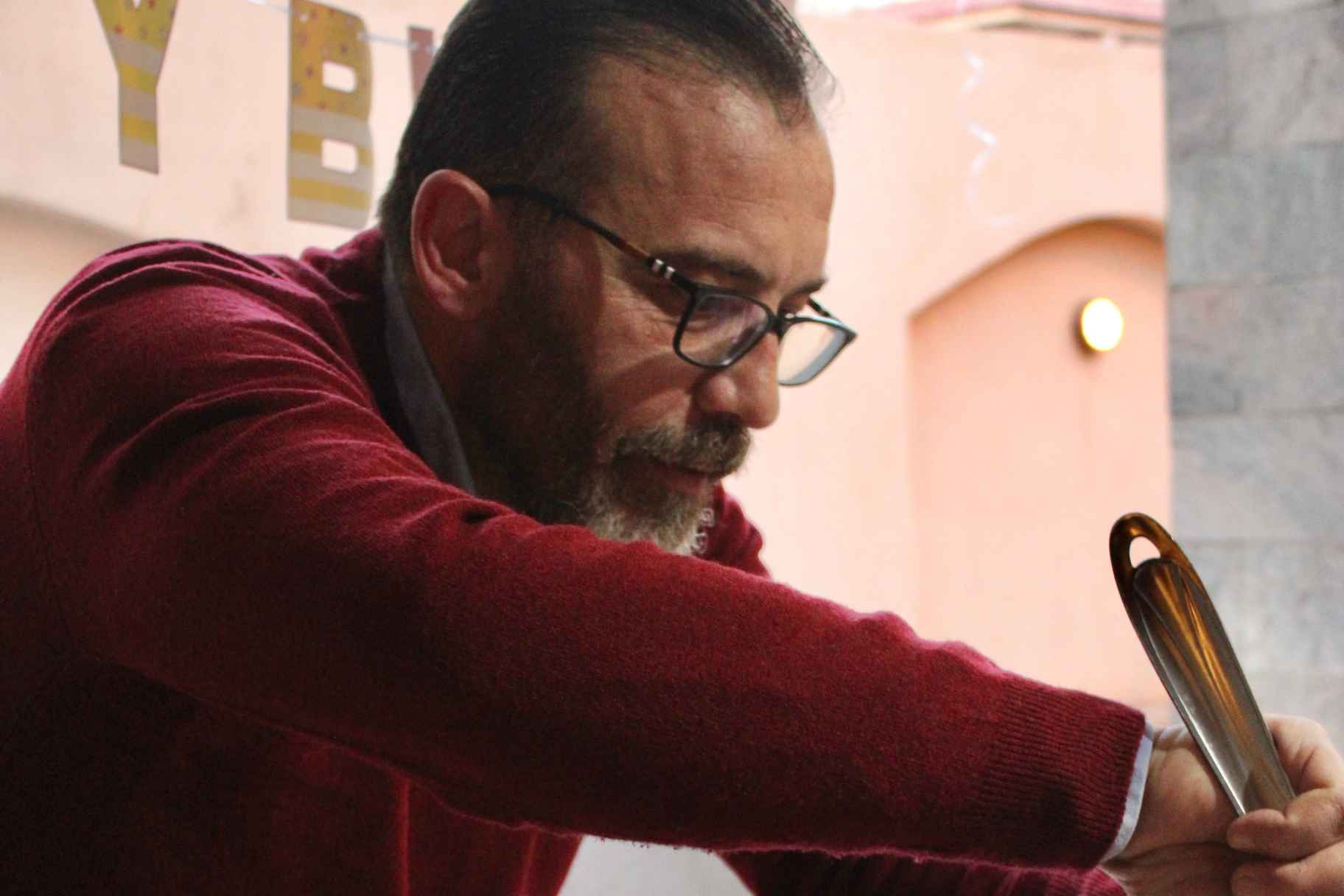

Pictured, Abu Arafat

Pictured, Abu Arafat

Known in his community not as Sohail, but Abu Arafat, Nour’s uncle is staunchly Gazawi and wants to return home as soon as possible. “If you told him he could go back tomorrow, he would go,” Nour said. His father, Nour’s grandfather, was a hugely influential activist in Gaza, and so, “Palestine and the Palestinian cause is rooted in us, as a family.” Not only that, but they are hugely proud of their family name, Arafat, “after our beloved Yasser Arafat.”

Matbakh Beat Setty, set up in February, is currently selling exclusively on Instagram at @matbakhbeatsetty. They sell freshly-made, truly authentic Palestinian food, a realisation of one of Soheil’s greatest ambitions. His other businesses were more quick-serve, but he always dreamed of his own restaurant serving only traditional Palestinian cuisine. “So although it came out of a struggle, Matbakh Beat Setty has always been a dream of his,” Nour said.

Every family member has a designated role on the Matbakh Beat Setty Team, Nour explained. Abu Arafat is the chef, obviously, his two sons work as the accountant and the errand boy, Nour’s father is in charge of sourcing and “important phone calls,” and Nour’s sister is responsible for marketing and social media. Nour herself holds the official title of ‘Manager of Customer Service’, but prefers ‘Quality Control Officer’, which really just means she tries all the food without asking, and then gives unsolicited feedback.

Armed with her experience as ‘Quality Control Officer’, Nour recommends their msakhan, made with a romantic amount of garlic and onions. Half a chicken is currently priced at EGP 280, although subject to change, and comes with fresh Palestinian bread, but if you really want to feast, a whole chicken sits at EGP 550. “Some people think our prices are too high, but my uncle gets up early every single morning to go and buy the fresh ingredients for the day. We want the food to be really fresh, and honestly we don’t usually have the space to bulk buy ingredients because we work from our own kitchen. It’s much smaller than a restaurant.”

A Matbakh Beat Setty bestseller Nour told me I have to try is an invented Gazawi salad they sell, fondly named ‘kishkiya’. A mix of labneh, green olives, mint, onions and olive oil, it is a charming side dish to either the classic msakhan or their very popular slow-cooked chicken fukhara. Matbakh Beat Setty also sells authentic Palestinian tabbouleh and mutabal, as well as high-quality produce like dukkah, olives and olive oil, which they source from a relative in El Arish, near the Rafah border.

The customer pays for delivery, using Uber or InDrive, so for those east of the Nile and craving the Palestinian dishes that are perhaps more easily-found in Downtown, or high grade Palestinian produce, Matbakh Beat Setty is operating in your area.

Shereen and Fatma Sabbah, Freelance Translators, & Ola Sabbah, Photographer:

I went to visit the Sabbah sisters at their new home in Rehab, where they plied me with homemade basbousa, apple juice and coffee, so when I left hours later, I was feeling very well-fed. Shereen, Ola and Fatma arrived in Egypt on May 1st, along with Fatma’s husband, Ahmed, and their children. The three of them have three more sisters, one of whom gave birth to a baby boy only two months ago, and three brothers who are still in Gaza with their mother, stuck there after the Rafah border was closed a week later. One more Sabbah sister is living in Portugal at the moment, and is safe.

Five whole months went by after October 7th before the Sabbah family even began to consider leaving Gaza. “It never occurred to us to leave,” Shereen recalled. “We thought we could wait it out like always. Even when Netanyahu said on TV that the war would last a year, we laughed because we thought that was impossible.”

Shereen, right, Fatma, centre right, and 3 of their sisters

Shereen, right, Fatma, centre right, and 3 of their sisters

Shereen works for a Canadian company doing online Arabic-English translation work, and since the owner is half-Palestinian, he has been incredibly understanding throughout the year.

Fatma and Ola have been less fortunate, and are searching for work in Cairo. Fatma also does freelance translation work and scores odd jobs to help them through the month, but cannot afford to commute from Rehab to central Cairo for a steadier income, or leave her traumatised children at home without her. Her children miss home very much, she told me, and ask her every day if she thinks the toys they left behind are still okay.

Ola was a freelance photographer in Gaza, with a big smile and a sunny disposition, but is struggling to find photography work here. While we nibbled on basbousa, she showed me beautiful photos and videos she took of weddings back in Gaza, and then tearfully pointed out who has not survived the Israeli onslaught. She told me she just wants something to do, even if it cannot be photography right now.

“She could be a really good receptionist, or work in public relations,” Shereen exclaimed, and I agreed. Ola was a delight. She made me feel welcome the minute I stepped through the door, and clutched my hand for the rest of the evening while we chatted like girls about ‘The Vampire Diaries’ - Ola is Team Stefan, and we all ostracised her for it - and how Snapchat memories never fail to ruin your day. For me, it is reminders of old flings that ended badly, but for them, it is pictures of buildings in Gaza that are no longer standing, with friends that are either stuck there or dead.

Ola Sabbah

Ola Sabbah

“The simplest pleasure since coming to Cairo has been the water, waking up to wash my face and drinking water,” Shereen sighed. “We couldn’t do either of those things for months in Gaza.” She described to me how she started drinking highly polluted water from an opaque bottle she found, just so that she could not see what nasty things were floating in it. “In my first few days here, I couldn’t shower without feeling like I was choking. The size of the shower made me feel so claustrophobic, it made me feel like I was trapped under the rubble.” While displaced, getting trapped under the rubble was their biggest fear, even more than dying. They made sure to stay at the tops of buildings so that if the IDF struck, the building wouldn’t collapse on top of them.

“Our whole lives are a constant state of ‘I don’t know yet’, and it’s exhausting,” Shereen and Fatma said. With no steady jobs in Cairo among them, there is nothing keeping the Sabbah family here, but they also don’t have the means to leave yet. “Egyptians are such good people,” they added. “They really love Palestinians, but we don’t want to be pitied.”

Fatma’s husband, Ahmed, was a certified mechanic in Gaza for 15 years, and had his own workshop with his brother where they repaired all kinds of cars, company vehicles and ambulances. “He was known all over Gaza,” Fatma said proudly. “But he used to be his own boss, and now every job here is offered out of pity.” Ahmed continued to work odd jobs in the South of Gaza, even after they were displaced and his workshop was destroyed. “He can’t sleep anymore, because he worries about being the breadwinner for us, and there is no good work for him here.” Fatma and Ahmed are considering joining her sister in Portugal if they can, where Ahmed could rebuild a more permanent career. With little intention to stay in Cairo, the couple are reluctant to invest what savings they have left on a workshop and all the mechanical equipment he requires.

Mohammed Salem, photographer and photojournalist:

I met Mohammed Salem for the first time at the Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale in Mounira, where he participated in an exhibition in April. A photographer and photojournalist, he came to Cairo on October 4th, 2023, only narrowly missing the escalation. He had been trying to find a job outside of Gaza for two years prior to ensure a better future for himself and his family.

As one of the founders of UntoldPalestine, a storytelling platform for and about Palestinians, he has worked with many local and international agencies, including Al Jazeera English. Now, however, after watching the genocide continue for nearly a year, he finds himself struggling to locate the passion or energy to engage with his photography. Gaza, his muse, is destroyed, and with it, his creative drive.

He recently held another exhibition entitled ‘Gaza Habibti’ at the French Institute of Alexandria, which he described as a lamentation of the city he left behind, a display of “moments untouched by the harshness of war.” He sees the photos he took before he left as precious, immortalised snapshots of places and faces now reduced to rubble and ruin.

He recently held another exhibition entitled ‘Gaza Habibti’ at the French Institute of Alexandria, which he described as a lamentation of the city he left behind, a display of “moments untouched by the harshness of war.” He sees the photos he took before he left as precious, immortalised snapshots of places and faces now reduced to rubble and ruin.

Mohammed told me he is waiting for the war to end so that he can return home. Although he was not pushed out of Gaza after October 7th, like most of his peers here, he has grown weary of being away from home, and he never got to give his Gaza a proper goodbye.

Photo credit to Mohammed Salem

Photo credit to Mohammed Salem

These are the stories of only eight displaced Palestinians who made it to Cairo out of 115,000, and it is purely for the sake of coherency that I could not include more. Approximately two million people remain in Gaza, including the surviving family and friends of Omar, Shahd, Zohud, Nour, Mohammed, and the Sabbah sisters.

According to figures published by the Lancet on July 5th, 2024, the unregistered death toll could exceed 186,000, but Palestinian health authorities recorded over 30,000 deaths, of which 70% were women and children, before the healthcare system collapsed entirely in February.

Multiple grassroots organisations were born in Egypt after October 7th, specifically to mitigate the influx of traumatised refugees arriving in Cairo and beyond, like Network for Palestine, Abawab El Kheir and Sanad, which was founded by Amal Awni, a refugee from Gaza herself. The Mersal Foundation also organised important aid packing, sending food, clothes and medicine to the Rafah crossing before its closure on May 7th.

Something that was expressed by each individual in every conversation was a longing to be able to stop relying on the good work of Palestinian charities in Cairo, but rather to have the capacity to support themselves and their families without help. They explained how this was a huge part of restoring a sense of freedom and control in displaced Palestinians, which cannot be replaced by charity forever.

It is my hope that, despite building frustrations, Egyptians in Cairo can continue to transform their despair into tangible support, to ease Palestinian grief for both their tangible and their intangible losses. By leaning into professional solidarity with Gazans in Cairo just as much as personal solidarity, Cairenes can return to them that sought-after financial stability and self-sovereignty, and enable Palestinians to build their new lives here, for themselves and by themselves.

- Previous Article WATCH: Rakeen Saad on ‘Seeking Haven for Mr Rambo’

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Mar 11, 2026