Nadia Lutfi: Movie Star, Cultural Icon, Freedom Fighter

We take a glimpse into the life of 20th century Egypt’s most politically active actress, from the frontlines in Sinai to occupation in Palestine.

Originally Published August 22nd, 2024

“My memories are a tapestry where the threads of politics and art are interwoven; much like the scent of gunpowder and the 'plateau', movie stars and freedom fighters, celebrities and others that may seem unknown, yet left an indelible and even dangerous impression upon me,” is the opening of Nadia Lutfi’s diary, ‘My Name is Paula: Nadia Lutfi Speaks’, compiled by renowned biographer Ayman Al-Hakeem.

The cinematic oeuvre of the ‘Lady of Egyptian Cinema’ stands as a remarkable intersection of Egyptian popular culture and the shifting sociopolitical currents of the mid-to-late 20th century. As one of the most celebrated artists of her generation, Lutfi's body of work - from ‘Al-Nadara Al-Saudaa’ (1963) to ‘Abi Fawq Al-Shajara’ (1969) - provides a compelling lens through which to examine the evolving representation of womanhood, nationhood, and modernity in the Arab world during this transformative era.

To know Nadia Lutfi was to be drawn into the very heart of Egypt itself - its mysteries, its desires, and its stubborn resilience in the face of an evolving world. In the end, she remained an enigma, a creature of light and shadow. Hers was an odyssey of uncompromising conviction - and all the world, mere spectators.

Before Nadia, There Was Paula

For years, word had it that Nadia Lutfi, born Paula Shafiq, is of Polish origins. No one is certain as to where or when this claim sprouted, but it is easy to see why it took. Long blond tresses frame a gorgeous visage; whiskey eyes accentuated by thick brows, a Greek nose, and thin perfectly bow-shaped lips, which make her seem like a ‘classic European beauty’. Her name, of course, only spurred the rumour mill.

In fact, her own name confused her, and she “lived for years thinking that this name that my father had chosen for me was the name of an old lover of his before he became involved with my mother. That remnants of her love remained in his heart, prompting him to give me her name, ensuring that it would remain on his tongue forever with no one being the wiser!”

However, the story behind Paula’s name is a beautiful one.

On the dreary morning of January 3rd, 1937, Mohamed Shafiq and his wife Fatma Khairy, hailing from Upper Egypt, made their way to the Italian Hospital in Cairo as Fatma's labour pains intensified. Her cries pierced the night, and eventually, she lost consciousness. The doctor struggled with his own anxiety, death’s shadow hovering in the corner of the room.

Outside, Mohamed paced the corridor, fervently praying for her relief.

“Amidst this turmoil, a nun dressed as a nurse offered hope. [...] Her unwavering optimism and kind demeanour seemed almost divinely inspired, easing the husband’s anxiety and bringing a glimmer of light to a dark, starless night.

At last, the awaited news arrived: the birth was successful. The dawn’s call to prayer heralded the arrival of a new day and a baby girl—me. My father, overwhelmed with emotion, embraced my mother and me, naming me Paula in tribute to the nun who had been his guardian angel,” Nadia wrote in her diaries.

Paula quickly grew into a cheeky child; precocious, quick-witted, shaqiya, regularly terrorising the residents of every Cairo neighbourhood she occupied, from Abdeen to Heliopolis. Her deep curiosity was regularly encouraged by her parents, both of whom dedicated themselves to intellectual, artistic and political pursuits. Her mother, who was denied an education, refused to remain illiterate and was determined to go far beyond her ‘traditional’ role of serving the husband and raising the children. An autodidact, she taught herself to read and write, before eventually delving into history and art, eventually becoming enamoured with writing poetry.

Despite being an accountant, Paula’s father was incredibly passionate about culture and literature, and had a special interest in cinema. In his library, you would come across books about Hollywood and its stars, literature and its creators, history and its historians. As a child, Paula would often sit through her father’s retellings of a new film he watched.

“I also learned from my father his doctrine of political liberation. Throughout his life, he did not belong to a party or political faction, neither before the July Revolution nor after it. His slogan was: ‘Ana ma’ al-haq’ [I am with what’s right]. Like him, I did not join a party or political organisation. I was with al-haq wherever it was,” she explained.

His views on women were also quite progressive. He never linked superiority to gender: man or woman, rather, the value of people to him was measured by knowledge, talent, morals, hard work and competence.

“But I failed to inherit my father’s doctrine of ‘love’,” she wrote. “All eloquence is incapable of adequately expressing the great love that brought him together with my mother. [...] he loved her to the point of adoration, and I sometimes could not resist smiling when my father’s eyes sparkled as he repeated in my ears expressions of flirtation with my mother, ending with his favourite sentence: ‘Your mother is the most beautiful woman in the world’. I would listen to him in astonishment, he spoke as if she were Aphrodite or the Mona Lisa and not the woman who raised me and whom I see every moment.”

Desperate to arm her with a better education than their own, her parents enrolled her first in the French Notre Dame school before switching her to a German school, where she met her first - and ‘only’, in her words - friend, Enayat al-Zayyat.

Befriending a Shooting Star

Enayat al-Zayyat's name lingers on the edge of collective memory. Much of what we know about the profound, radical friendship Enayat al-Zayyat shared with Nadia Lutfi is owed to Egyptian poet Iman Mersal, whose chance encounter with al-Zayyat’s neglected novel ignited a quest to unravel the life of this enigmatic writer. This exploration, captured in Mersal's ‘Traces of Enayat’, reveals how their bond was inextricably linked to the seismic shifts in Egypt’s political landscape during the 1940s and 1950s.

“The face of Enayat al-Zayyat never leaves my thoughts. If she ever leaves my thoughts I can summon her back in seconds. [...] I was an only child and she became a sister to me, completed me,” Lutfi told Mersal.

The girls were classmates who bonded over their shared abhorrence of the ‘girls can’t do this’ and ‘young women should behave this way’ rhetoric that was deeply enforced by the terrifying Sister Cecelia of the German school. Nadia, who refused to wear dresses and was often caught playing with the boys in the streets, was famous across the school for always being up to no good which piqued the interest of quiet and seemingly demure Enayat. In turn, Enayat’s vast knowledge on politics and philosophy, her love of literature and cinema, pulled Nadia in, speaking to her heart in a way she’d only ever experienced with her parents.

Their relationship, forged in the crucible of Cairo’s cultural and political ferment, was a reflection of Egypt's own tumultuous journey. Lutfi's memories, recounted in ‘My Name is Paula: Nadia Lutfi Speaks’, reveal a partnership that transcended mere camaraderie: “If God had blessed me with a sister, I would not have loved her as much as I loved and bonded with Enayat. [...] it is more than friendship,” she recounts, “...we were similar in everything and fate did not separate us even after my marriage.”

For al-Zayyat, the struggle begins with her marriage. Her husband - a pilot - refused to let her finish her final year of schooling. Despite the union initially promising a semblance of stability, it quickly devolved into a harsh reality of gendered oppression and personal disillusionment. Three years into the abusive marriage, al-Zayyat decided to do the ‘unthinkable’ and filed for a divorce.

For over a decade, al-Zayyat bravely defied societal expectations in various ways. She fought for a position at the German Institute’s library despite lacking a baccalaureate, wrote her first and only novel, ‘Love and Silence’, and navigated life as a single mother while contending with the stigma of mental illness. Like all shooting stars - wild, magical, nebulous - its life is fleeting and its crash inevitable.

On Nadia Lutfi’s 26th birthday, al-Zayyat faced crushing setbacks: the threat of losing custody of her son and the rejection of her novel by the National Publishing House. Overwhelmed by these challenges, she took her own life.

“When they told me the news, I ran like a madwoman to her house. [...] I entered her room and locked the door. She was lying on her bed. I sat there talking to her, blaming her, and yelling at her, as if she was in front of me, hearing me: Why, Enayat? How could you do this? I started hitting the walls and furniture unconsciously, as if I was in a nightmare that I wanted to wake up from. The shock was too much for me, I could not attend her funeral because I did not want to believe that she was gone and I would never see her again.”

Enayat and Nadia’s friendship was emblematic of a generation grappling with an evolving national identity in an Egypt caught between colonial remnants and nascent independence, as well as the broader currents of war and revolution ravaging the region. Lutfi’s depiction of her friend’s plight - “Her revolt was not only against her personal situation, but against the entire society that violates women”- reflects a deeper, systemic critique of the societal structures that constrained and often brutalised women.

Lutfi’s own transition from the glamour of cinema to documenting the brutal realities of war and conflict can be seen as an extension of their shared commitment to challenging oppressive systems.

‘The Lady of Egyptian Cinema’ is Born

During the late 1950s, Nadia’s father, Mohamed Shafiq, a friend of film producer Jean Khoury, took her to a birthday party at Khoury’s house where she met producer Ramses Naguib. He offered her a role in his upcoming film ‘Sultan’, starring Farid Shawqi in 1958. It was Naguib who chose to name her ‘Nadia Lutfi’, based on Faten Hamama’s character - who carried the name - in the film adaptation of Ihsan Abdel Quddous’ ‘La Anam’. This delighted Paula, now Nadia, whose favourite silver screen star happened to be Faten Hamama.

Nadia’s initial start was not meant to be ‘Sultan’, however, but another work planned with Youssef Chahine. Unfortunately, it fell through due to Chahine leaving Egypt for almost a year. By the time he returned, Nadia had not only made her debut, but became an overnight sensation.

They would, eventually, work together on her second film ‘Hob Ila Al-Abad’ (1959), where Chahine helped her shed her own skin in favour of her character’s.

In her diaries, Nadia writes: “I remember we were filming the suicide scene. I got into the car and found Youssef sitting with me on the ‘car pedal’ next to the camera. We drove down Haram Street, and I was supposed to cry. I tried, but my tears would not come. ‘Think about your sick mother,’ he told me. ‘She’s not sick,’ I coldly replied. ‘Okay, think about when your father died,’ he replied. ‘He did not die,’ I spat back. ‘Okay, imagine your son screaming for you to breastfeed him,’ he said. ‘My son is old,’ was my last response.

I felt sorry for him as he continued to try to incite my tears. I was supposed to send a letter to my lover - Ahmed Ramzy - before my suicide. In a last ditch effort, Youssef began reading the letter to me with incredible feeling, and suddenly I found myself crying. I learned from this situation a lesson that has stayed with me all my life, which is that the actor does not elicit their feelings from a situation other than the scene they’re acting in, it must come from the scene, and their emotion has to be real and sincere. I never forgot this particular event. Whenever I got stuck with a particularly difficult scene, his voice would come to me.”

Nadia Lutfi's prolific career was defined by a remarkable versatility, as she seamlessly inhabited a diverse array of compelling roles.

In Salah Abu Seif-directed 'La Totfe' Al-Shams' (1961) and Hossameddin Mustafa’s 'Al-Naddara Al-Sauda' (1963) Lutfi demonstrated her dramatic prowess. Her portrayal of Louisa, the compassionate Christian missionary, in Youssef Chahine's epic 'Al-Nasser Salah Al-Din' (1963) further cemented her status as a cinematic chameleon.

Nadia's nuanced performances extended to literary adaptations as well. In Naguib Mahfouz's 'Al-Semman Wal-Kharif' (1967), she embodied Riri, a streetwalker who encounters a renowned writer grappling with existential questions.

Lutfi's range knew no bounds, as evidenced by her turn as a bored, possibly unfaithful wife in Kamal El-Sheikh's 'Al-Khaaina' (1965), alongside Mahmoud Morsi. She further showcased her talent in the biopic 'Badia Massabni' (1975) where she breathed life into the legendary singer, dancer and entrepreneur of the 1940s and 1950s.

Nadia's cinematic legacy also included a memorable cameo in Shadi Abdel-Salam's acclaimed 'Al-Momia: Laylat An Tohsad Al-Senin' (1969). Her most controversial, yet critically acclaimed, performance came in Hussein Kamal's directorial debut, 'Al-Mustahil' (1965).

Lutfi's iconic status was further cemented by her collaborations with the legendary Abdel-Halim Hafez. She shared the screen with the musical icon in 'Al-Khataya' (1962), directed by Hassan El-Imam, and in Hafez's final film, 'Abi Fawq Al-Shagara' (1969), the highest-grossing Arab film of the 20th century, again directed by Hussein Kamal. In the latter, Lutfi portrayed Fardous, a sensual cabaret dancer whose love for a young man ultimately leads her to sacrifice her own desires for his well-being.

Leaving the Silver Screen for the Frontlines

Lutfi’s first significant engagement in political and humanitarian work started prior to her acting career, during the Tripartite Aggression of 1956 - an international military intervention by Israel, Britain and France against Egypt following President Gamal Abdel Nasser's nationalisation of the Suez Canal. Driven by a deep sense of patriotism, she volunteered as a nurse to support her homeland during this critical period. Leaving behind the comforts of her affluent lifestyle, Nadia dedicated herself to treating the wounded at Al-Qasr Al-Ainy Hospital throughout the brutal aggression.

However, it wouldn't be until the Six-Day War or Naksa in 1967 when Israel launched rapid fire attacks against Egypt, Jordan and Syria that her activism would become public knowledge. Amidst the chaos and uncertainty, she returned to her role as a volunteer nurse, travelling to Sinai where the fighting had left many wounded. She would clean cuts, dig out bullets and stitch both skin and soul back together with so much kindness it drove people to tears.

During the years between 1967 and 1972, she’d immerse herself into humanitarian work, going beyond treating soldiers and becoming deeply involved in campaigning for and aiding families of Egyptian hostages taken by Israel.

In addition to her direct humanitarian work, Lutfi rekindled an old passion for filmmaking. This endeavour was not merely a creative outlet but a strategic effort to document and preserve the narratives of those directly impacted by the Zionist state. She travelled extensively, from the remote villages of Upper Egypt to the turbulent landscapes of Sinai, capturing testimonies from returned hostages and prisoners of war. Her film projects aimed to create a comprehensive record of the trials faced by Egyptians, including those experienced during the Tripartite Aggression of 1956, the Naksa, and the subsequent War of Attrition.

Through her meticulous documentation, Lutfi sought to establish a visual archive of the numerous war crimes committed against Egyptians by Israel. Her footage was intended to serve not only as historical evidence but also as a testament to the suffering and resilience of her people.

Somewhere between those years, she would also open up her home to Egypt’s intellectuals, literaries, journalists and artists. Whether they were looking to spill their thoughts or find help, they would knock on her door. Eventually, this led to her hosting a ‘Salon Thaqafi’ (Cultural Salon) at her Garden City residence, which regularly welcomed the likes of Ihsan Abdel Quddous, Youssef Idris, Naguib Mahfouz, Yahya Haqqi and was often moderated by Dr. Youssef El Sebaei. Lutfi had, in those years of defeat, transcended her movie star status and cemented herself as a cultural treasure. In fact, fellow actor Kamal El Shennawy would give her the nickname ‘Mawaqef Lutfi’, for her immeasurable gad’ana and the innumerable situations - political and social - where she would drop personal and work matters to rush to the aid of an oppressed individual or group.

Despite working on numerous films and volunteering during the war, Nadia did not forget to bring her camera with her. Between her and producer-filmmaker Shadi Abdel-Salam, they’d gathered enough footage to bring a documentary titled ‘Juyoosh Al-Shams’ (1973) to life, spotlighting the stories of soldiers who fought in the 6th of October War.

Lutfi’s activism, however, has never been concerned with just Egypt, a pan-Arabist at heart, she never shied away from proclaiming that her compass has - and always will be - Palestine.

“My concern with the Palestinian cause is both old and deeply rooted; it runs in my veins. [...] I have a deep-seated hatred of injustice and oppressors - this is a matter of principle for me. I am always a defender of the oppressed, regardless of their gender, colour, or identity. How could I not be concerned for our brothers who have faced injustice beyond limits and endurance?

The second reason is my recognition that Palestine is primarily an Egyptian issue. When we defend and protect Palestinian rights, we are also safeguarding, and indeed prioritising, Egypt's security and its eastern borders. Since the days of the Pharaohs, it has been evident that Egypt's security starts from Palestine; it is the first line of defence,” she told Al-Hakeem.

Lutfi’s engagement with the Palestinian cause began through cinema, with films centred on the occupation of Palestine. It started in 1962 when she starred in the film ‘Sera’a Al-Amaleqa’, written and directed by Zohair Bakkar with Ahmed Mazhar, Youssef Fakhr El Din and Tawfiq El Deken also in the cast. In this film, she played the role of a Jewish dancer of Egyptian origin who travels to Palestine, overcomes her own internal conflicts, and helps Egyptian prisoners escape from Israeli detention camps. In 1963, 'Al-Nasir Salah al-Din’, in which the conflict over Jerusalem was the main theme, hit the screens. And in 1967 she participated in 'Gareema fil Hayy Al-Hade'a', a film based on a true story about an Israeli spy network in the heart of Cairo.

This deep-seated concern with Palestine did not translate into radical action, however, until the Beirut Siege.

In June 1982, Israel launched Operation Peace for Galilee, invading southern Lebanon and besieging the capital, Beirut, in a clear breach of the ceasefire imposed by the United Nations. Israel claimed it did so with the aim of trapping the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) in an effort to drive them out of Lebanon.

In her diaries, Lutfi writes: "On that heavy summer morning (June 6, 1982), I woke up to the news of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and the audacity of a war criminal like Ariel Sharon (who was the Minister of War in the right-wing government of Menachem Begin) to invade an Arab capital with his forces. At that moment, I felt that my dignity had been insulted, and I was overcome by a violent anger that increased and multiplied as I followed the news coming from Lebanon.

I was not alone. A state of anger and mobilisation took over artists and intellectuals in Egypt, and they raced to donate blood and issue statements of condemnation and denunciation, but I felt that it was a weak reaction that did not match the enormity of the event.”

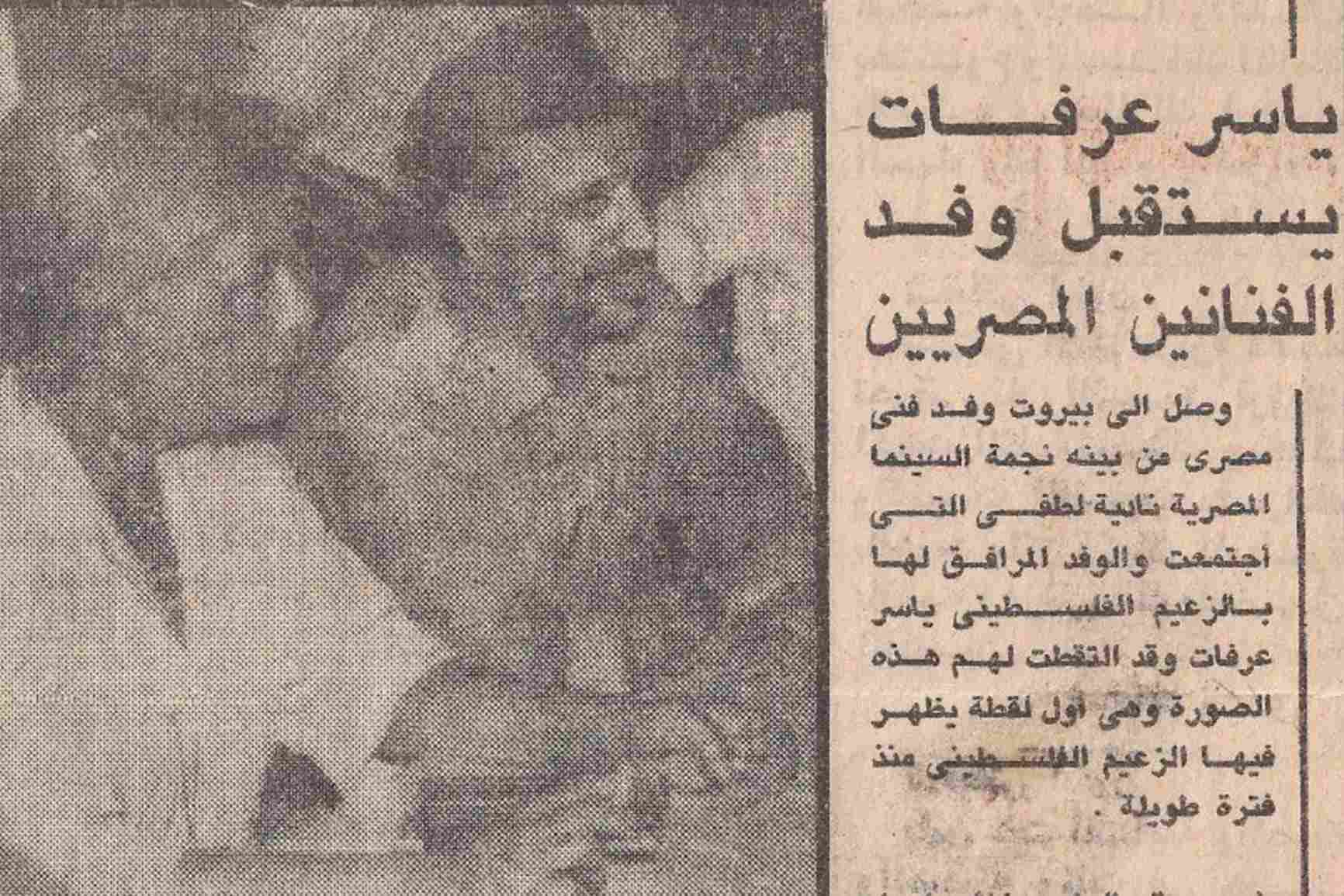

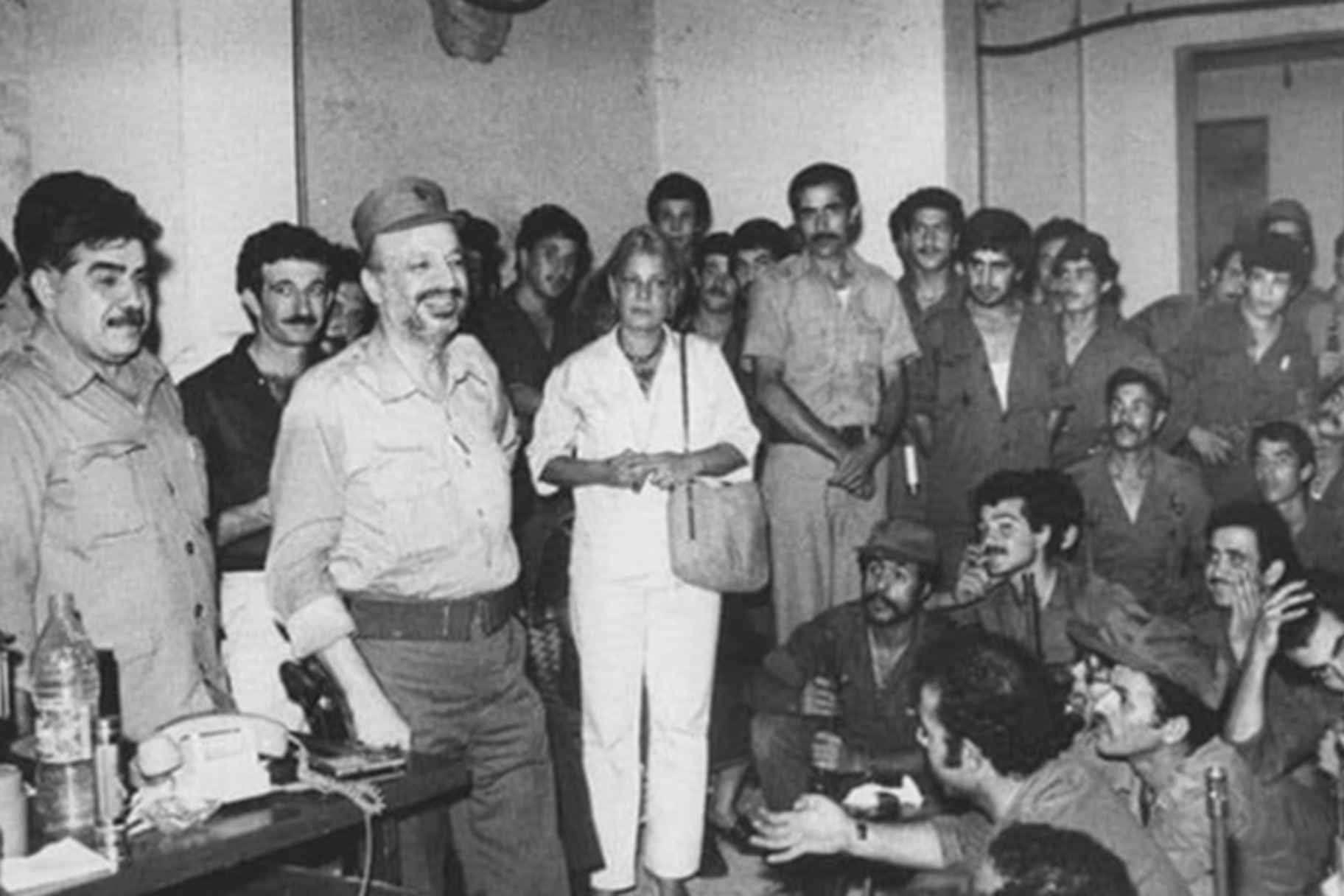

The Elected Chairman of Arts Syndicate Federation at the time, Saad Eddin Wahba, called for an emergency meeting, and crowds of creatives and intellectuals from all backgrounds rushed to attend. During the meeting, Lutfi suggested that a group of famous figures travel by sea to Beirut and sneak into the besieged city to support the Palestinian resistance, and while a few welcomed the suggestion, the majority was heavily opposed.

Never one to give up on an idea once it rooted itself in her, she decided to take on the quest by herself.

The next day, she packed her bags, gathered some supplies, called Laila El-Sherbiny, a professor of physics and pure mathematics and her friend, and took off via boat to Cyprus before boarding another boat to Beirut.

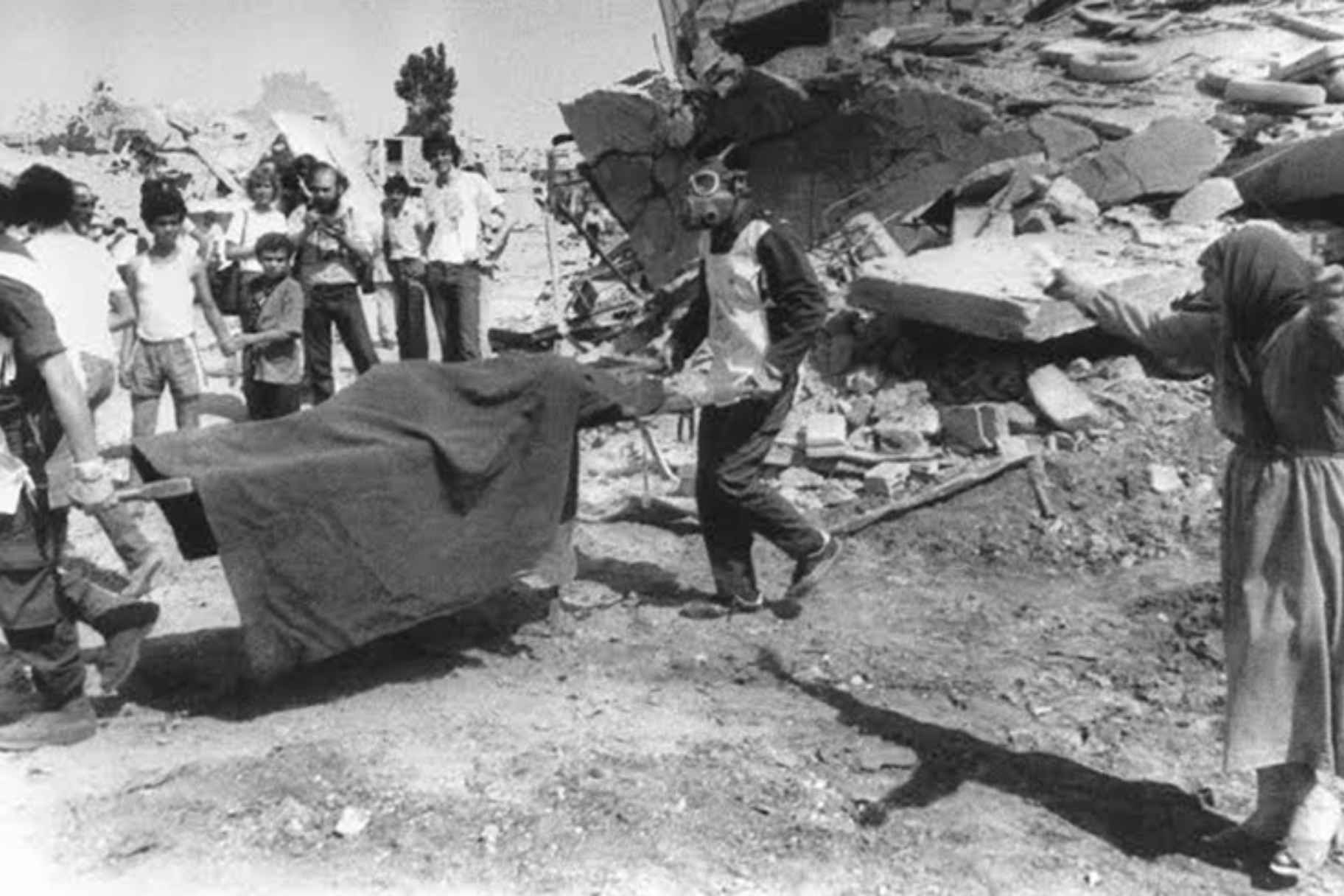

For two months, Lutfi lived with the PLO fighters - learning from them, tending to them, caring for them, starving with them - and it earned her a new name amongst them, ‘Al-Fida’iya Al-Helwa’ [The Beautiful Freedom Fighter]. Of course, she also developed a lifelong friendship with PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat. Nadia witnessed - and filmed - numerous battles and massacres during her time in Beirut, the most heartbreaking of which was the Sabra and Shatila refugee camp massacre, where Israeli-backed Phalange militia killed between 2,000 and 3,500 Palestinian refugees and Lebanese civilians in only two days. Over 25 tapes contained the hours she filmed of the massacre and much of her footage was picked up by international news agencies, with articles across the world echoing the same sentiment, “Nadia Lutfi did not have a camera, but rather a machine gun pointed at the Israeli occupation forces.”

Years after the siege, Arafat - then President of the Palestinian National Authority - visited her at her Cairo home and gifted her his keffiyeh in honour of the role she played in raising the resistance’s morale and documenting the heinous crimes of the zionist state.

In Loving Memory

“I am not just Nadia Lutfi the actress or star or whatever it is you want to call me. I am Paula Mohamed Shafiq, the human being, the Egyptian who has lived a life full of great moments, been through war and peace, seen happiness and many many tears, and is still fighting to make this planet a more livable place.”

This has been a mere glimpse into the rich life of one of the most prolific personalities in modern Egyptian history. May her life be a reminder that art is meant to be a method through which to engage in politics and her sacrifices on the road to liberation - for Egypt, Lebanon and Palestine - inspire generations to come, until we can catch a bus from Cairo to Jerusalem once more.

- Previous Article Palestinian Artists El Far3i & Rula Azar Unveil ‘Walladah’

- Next Article Six Unexpected Natural Wonders to Explore in Egypt