Nadine Nour el Din on Curating Doria Shafik and a Legacy of Resistance

Through portraits, publications, student designs, and rare archival material, the exhibition traces Doria Shafik’s political activism, feminist vision, and enduring influence on modern Egypt.

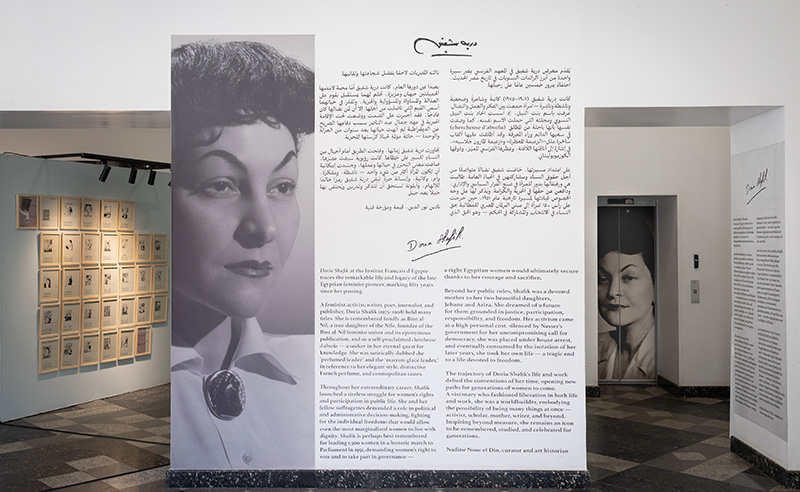

Through portraits, publications, student designs, and rare archival material, the exhibition traces Doria Shafik’s political activism, feminist vision, and enduring influence on modern Egypt. At the Institut Français d’Égypte in Mounira, an exhibition marking fifty years since the death of Doria Shafik revisits the life of one of the defining figures of Egypt’s mid-century feminist movement. Curated by London-based art historian Nadine Nour el Din — whose work spans visual arts, feminist research, and the study of modern Egyptian print culture — the show assembles photographs, manuscripts, publications, and archival material tracing Shafik’s trajectory from her education and early writing to the period of political activism that shaped her public legacy.

Nour el Din, who studied Visual Arts at the American University in Cairo followed by graduate degrees in arts management and cultural policy at Goldsmiths and in the history of art at the Courtauld, approached the project after years spent researching women’s histories in the region and building her own archive of mid-century Egyptian magazines, including issues of Bint al-Nil, the magazine Shafik founded in 1945 and later developed into the Bint al-Nil Union.

For Nour el Din, the central challenge was how to build a visual exhibition around a woman who resisted acquiring or preserving many material possessions. Shafik’s life was grounded in writing, organizing, and political intervention more than in objects, which forced the exhibition to lean heavily on archives rather than personal belongings. The process revealed the extent to which her intellectual world survived in documents rather than in things, and how reconstructing her story required navigating multiple institutional collections, family archives, and scattered ephemera.

Shafik’s political work formed the backbone of the exhibition. Her involvement in the women’s movement, her march into Parliament in 1951, her protests against colonial authority, and the years of enforced seclusion that followed all shape the narrative on display. The exhibition is in part a tracing of her public actions, but it is also, in equal measure, an ingress to the quieter parts of her life, including her private writings and later manuscripts produced during her isolation.

A separate part of the show engaged with Bint al-Nil. The publication served as both a journal and an organising platform advocating literacy, social support, political participation, and legal reform for women. Its pages moved between political analysis, social commentary, practical columns, and cultural material, offering insight into the debates shaping Egyptian womanhood in the 1940s and 1950s. For the exhibition, these issues provided a rare concentration of visual and textual material, illustrating the breadth of Shafik’s engagement with questions of rights, education, and civic life.

When were you first introduced to Doria Shafik?

I first came across her in my research. I work a lot on artists from the Arab world and the wider region, and within that, I’ve focused for several years on feminist art history because women artists, and women in general, are underrepresented in art history. I’ve also been collecting an archive of magazines from modern Egypt, and that’s where I found her — through my feminist research and through issues of Bint al-Nil, which appear in the exhibition and come from my collection.

When the Institute approached me because her family had chosen me to curate the show, I was really happy. I felt it was time she received recognition, especially because a whole generation doesn’t know her due to the violent silencing she endured. In the Al-Ahram archive, for example, she appears actively and then disappears completely — no search results, just two death notices in 1975, then nothing until the late 1990s and early 2000s. She isn’t in school curricula, so students don’t encounter her the way they do someone like Huda Sha’arawi. That’s why collaborating with the Children’s Book Festival was important for me. I presented educational material so children could learn about her outside the traditional curriculum.

How did you begin to conceptualise the exhibition itself?

For me, any exhibition starts with the human aspect. Who was the actual person? There’s always a public persona, but I’m interested in the person behind it. My entry point is always the family. I sat with her daughters, Jehan and Aziza, in long, emotional conversations, asking about her childhood, what she was like, and the smallest details — her favourite song, her perfume — the things that help build the scaffolding of the curatorial framework. Those conversations became my source material.

The challenge with Doria Shafik is that she didn’t leave many objects behind. The Bint al-Nil union was burned down; her own belongings were minimal; even the Bint el Nil magazines are bound compilations rather than individual issues. So I had to rely on my own archive and think: how do you make a visual exhibition out of the life of someone who was primarily a writer and thinker?

I pulled different materials from her books. In My Trip Around the World, the first edition has a final section of annotated photographs from her travels. Another book published the same year, The Egyptian Woman from the Pharaohs Until Today (1955), includes illustrations by Abdelsalam El Sherif, each introducing a chapter. Those images give us a visual sense of the topics she writes about.

We also have her actual necklaces on loan from the family, and portraits of her by both modern and contemporary artists. Edmond Soussa painted her, as did George Daoud Corm, and there’s a bust by an unknown German artist who lived with her for several months. Van Leo’s famous portrait comes from AUC’s Rare Books and Special Collections Library. And then there are the contemporary works — especially three pieces by Chant Avedissian from his Icons of the Nile series, each owned by a different family member.

Photographs come from multiple sources: AUC’s Rare Books and Special Collections Library; the Palestinian Museum’s digital archive (images from her 1955 Jerusalem trip); and her letters to Huda Sha’arawi from the AUC Sha’arawi Collection. Al-Musawwar magazine appears courtesy of my archive, as do the Bint el Nil materials. So I had to widen the sources as much as possible.

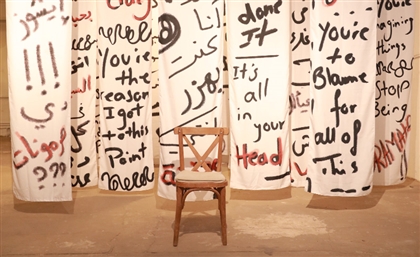

There’s also a section of fashion design works — student projects from GIU under Professor Kegham Djeghalian, created through a collaboration with Maison Dior. The students used Dior’s codes and Doria Shafik as a point of reference. They each focused on different aspects of her life to design garments and Lady Dior bags. These were shown at Cairo Design Week last year; Kegham and I selected a small number for this exhibition so they wouldn’t overpower the show. One is by Youssef Tawakol, who imagines “Super Doria,” envisioning what she might wear if she returned today. These works form part of the “legacy and liberation” section — reflecting how her influence continues for people who never met her.

Because her publishing and public-speaking work were central to her activism, it was important for me to create a platform for Egyptian women in the exhibition too. I invited women from different fields to comment on her life. You’ll find quotes from Noura Simoni-Abla on Doria as someone who balanced motherhood and career; Sarah Rifky reflects on portraiture and hunger strikes; and writer Alya Mooro and Nihal el Aasar reflecting on her feminist activism and even her favourite song.

What can Bint al-Nil tell us about the political atmosphere for the feminist movement in the 1950s and 60s?

Bint al-Nil gives a full picture. Through her editorials, we get her political voice — very sharp, very clear — and they align with the research she presents in her books on women’s activism. But it’s also a women’s magazine: fashion, product advertisements, runway looks from Paris and London, French perfumes (fitting, because her favourite perfume was French), satirical quizzes, recipes both local and regional. It was hard to choose which pages to display because the scope is so broad.

Ultimately, Bint al-Nil is a microcosm of the moment: the cosmopolitan Egyptian woman and the aspirational sense that you can do everything — dress well, run a household, be a “perfect” wife, be involved in politics. What I find striking is the irony that Doria Shafik herself didn’t necessarily do all the domestic things the magazine advocated, according to her daughters.

Her birthday is coming up on December 14th. How do you see this exhibition contributing to a new generation discovering her?

Her daughters planned a series of events for the 50th anniversary of her passing. Before the exhibit, there was a poetry reading; after it, there will be a book launch — the Arabic translation of Cynthia Nelson’s biography is being reissued by Dar el Shorouk.

For me, the exhibition does important work by presenting the different facets of her personality. The show is divided into chapters: her quest for knowledge, her role as a voice of resistance, her identity as “Bint al-Nil,” her years of silence, and her portraits. If you already know her, you see sides you may not have seen before; even her daughters learned new things. If you don’t know her, you completely meet her. And people can approach it at their own level: some sit and read everything, others engage visually.

Accessibility was a priority. The large vinyls, for example, during installation, no one reacted to the walls being painted, but as soon as the vinyl went up, everyone began asking who she was. That’s the point: people who didn’t know her are now encountering her. And getting schoolchildren involved was a major goal for me. Even if what they walk away with is her name and a few facts, that’s meaningful.

I spoke to her daughters on opening night, and they said she would think progress today hasn’t advanced as much as it should have. In one of your previous statements, you voiced a similar concern. Could you elaborate?

When I read her 1955 book on Egyptian women from ancient times until the present, she traces the history of feminist activism and the advances that women have made. And sadly, as I read it, I felt we haven’t advanced much beyond that point. It’s quite heartbreaking. But it’s also a reason to celebrate her — she was fundamental to women gaining the right to vote, and that’s a major reason we progressed at all. Still, I think we’re in a similar political climate today, and her story becomes a lesson for us: something to learn from and draw strength from.

Installation views from Doria Shafik at the Institut Français d’Égypte, curated by Nadine Nour el Din and photographed by Marc Onsi.

Archival photographs from the Doria Shafik Collection, courtesy Rare Books and Special Collections Library, The American University in Cairo.

- Previous Article Select 365: Mixed by Banx

- Next Article January 1st Announced as Public Sector Holiday for New Year's Day

Trending This Week

-

Feb 16, 2026