Suad Amiry on Defending Palestinian Identity Through Cultural Heritage

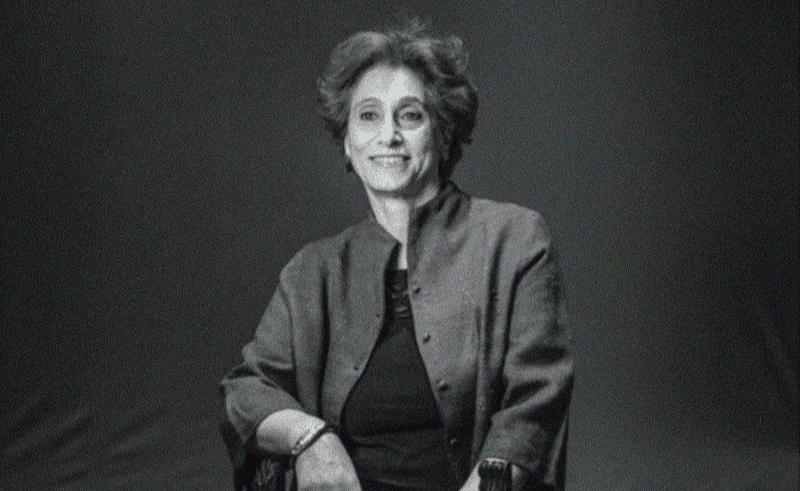

"The protection of cultural heritage is the protection of memory and identity." Author and architect Suad Amiry speaks with us about protecting Palestinian identity in the face of Israeli erasure.

Suad Amiry is a Palestinian author and architect, and the founder of the RIWAQ Centre for Architectural Conservation in Ramallah. Her latest novel, 'Mother of Strangers' (2022), unfolds in Jaffa between 1947 and 1951, tracing a love story through the years in which Israeli forces established their occupation, displaced Palestinians, and destroyed their homes. Whether through her writing or her work safeguarding architectural heritage, Amiry has long advocated for the preservation and visibility of Palestinian identity.

Based in Ramallah since 1981, she founded RIWAQ in 1991 to document and revitalise cultural heritage sites across the West Bank, Jerusalem, and Gaza. But today, their work across the increasingly fractured Palestinian territories is under threat by Israel. In Gaza, RIWAQ architects continue to do whatever is possible to reconstruct heritage sites, efforts often halted or reversed by ongoing Israeli bombardment. Israeli forces also separate RIWAQ from its archives in Jerusalem through a network of physical barriers—checkpoints, fences, and the concrete wall—that have only expanded since the late 1990s. These structures sever Palestinians in the West Bank from Jerusalem and large parts of their native lands, while settler and military attacks continue to escalate across the West Bank.

Amiry sat down with CairoScene to speak about the origins of RIWAQ, the urgency of their work in Gaza, and what it means to continue operating across Palestine in the face of occupation and genocide.

What inspired you to found RIWAQ?

I grew up in Jordan as a refugee, the daughter of a refugee. My father always talked about their neighbourhood in Jaffa al-Manshiyya that the Israelis demolished completely. And then he told me about the 420 villages that the Israelis destroyed between 1948 and 1952. And that number, as a kid, haunted me—the fact that somebody can bring a bulldozer and just simply erase that.

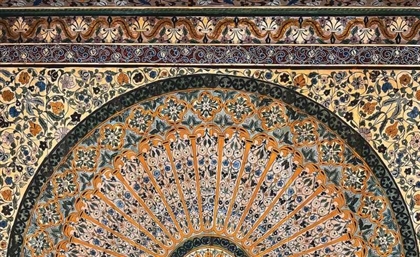

I ended up studying architecture. The first time I came to Palestine, I decided to travel around and see the existing villages, but also see the ones that the Israelis had demolished. I noticed that in Palestine in the early 80s, the villages were really, really beautiful. They were very nicely integrated with the landscape, which is mostly olive trees and some almond trees. And I was interested in how the social formation of a village reflects itself in the spaces of those villages.

I ended up feeling the need to protect these places, because when I arrived in the 80s there was only protection for religious buildings in Jerusalem. The Muslim Waqf were protecting al-Aqsa, and the Christians were protecting the churches. And nobody really cared—not only about the cities, but also—about the villages in particular.

I took that as a mission to protect whatever remains from the Israeli destruction of our cultural heritage. But also, how beautiful it was was another reason for me to start RIWAQ. So in ’91—I arrived here in ’81—I spent ten years researching, not only for my doctorate, but also with the students of Birzeit University. And then I decided it’s time to start an organisation whose aim is the protection of the cultural heritage.

How did you accomplish that aim across Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza in RIWAQ’s early years? Was it easier to move between the Palestinian territories back then?

When we started, we created something called the National Registry of Historic Buildings. We sent hundreds of architecture students and archaeology students, and we documented around 50,200 buildings in Gaza, East Jerusalem, and the West Bank. At that time it was possible to go to Jerusalem from the West Bank; it was also possible to go to Gaza.

So, the National Registry has a record of what existed in the 90s. But as we know, the difficult political situation is getting worse every day in Palestine, to a point where now we can’t reach Jerusalem—even Arab East Jerusalem. And of course, Gaza is off-limits to everybody.

We’re glad to have a record of what was in Gaza as a city and villages, but now we are more concerned about protecting that archive, because in Gaza, people and the municipalities lost their archives. So, we work with a number of architects and engineers in Gaza on the protection of cultural heritage, and they have been working even in the darkest days. But it’s only a drop in the ocean.

How do you continue to work in Gaza today under constant Israeli bombardment? What do you do to protect your architects?

When the war against Gaza started almost two years ago, we had to protect our architects and had the responsibility to continue providing them with an income. And whenever it was possible for them to go and document sites—for example, al-Omari Mosque, which was totally destroyed—they went to search for and number the stones and document as much as possible in the destruction, so that in the future, if there is a possibility of reconstructing, at least we know where these stones are.

We have also, in the past, protected a number of palaces or mansions in Gaza. So when it’s possible for them to go, they visit these projects that we have worked on in the past, to take photos of their current state or destruction, and also to see if the stones are there, protect the stones, number them—things like that. But more so to continue providing them with an income.

What does it mean for RIWAQ to not just restore buildings, but build spaces that keep memory alive and serve Palestinian communities today? Over 35 years, we worked in Jerusalem, Hebron, Nablus, Ramallah, Bethlehem, Jericho, we worked in the villages, we worked in Gaza. And it’s not only the work of RIWAQ; it’s also the people who came to work with RIWAQ. We created a generation of people who believed in the importance of cultural heritage as a way of resistance, as a way of maintaining identity, as a way of maintaining memory.

Over 35 years, we worked in Jerusalem, Hebron, Nablus, Ramallah, Bethlehem, Jericho, we worked in the villages, we worked in Gaza. And it’s not only the work of RIWAQ; it’s also the people who came to work with RIWAQ. We created a generation of people who believed in the importance of cultural heritage as a way of resistance, as a way of maintaining identity, as a way of maintaining memory.

And memory is very important, because what the Israelis wanted when they destroyed the 420 villages was to erase memory, to erase the existence of the Palestinians. And for me, the most important thing is not to allow that. So the protection of cultural heritage is the protection of memory. And the protection of memory is the protection of identity.

But also we created, let’s say, a school in architecture which is about adaptive reuse. We’re not creating new buildings. We are protecting the existing ones, and we are making them usable by the people. For example, we restored the old Ottoman court in Bethlehem, and we made it into a children’s library. We restored an Ottoman palace in Ramallah, and we made it into a cultural centre. In Birzeit, we restored an Ottoman khan and made it into a museum. So it’s not only about protecting the stone, it’s about making these buildings alive, usable by people, and creating a new economy around them.

During restoration, you create jobs. And for us, it was very important to create jobs for young architects, young engineers, and also stone masons, carpenters, blacksmiths, because they were losing their jobs, as there were no new buildings for them. We created a whole economy around the restoration of buildings. In doing that, we also created respect for heritage, because people started seeing these buildings not as ruins but as useful places. We insisted that these places should be for the community, not for private use.

We never restored a building to make it into a hotel, for example. We always restored it to make it into a public building, for the community. That was very important for us as an organisation, because we wanted the community to feel that cultural heritage is theirs, not only for the rich, but for everybody.

In addition to economic empowerment, you’ve mentioned that women’s empowerment is central to RIWAQ’s mission.

From the beginning, I believed that women should be empowered, especially in our field. Architecture was a very male-dominated field, and I insisted that 50 percent of our employees should be women. I insisted that the women should be given responsibilities. This was very important, because now you see many women architects who came from RIWAQ and are leading in the field.

RIWAQ was not only about cultural heritage, it was also about creating a new generation, creating an economy, creating respect for women, creating a way of resistance.

Given the threats to heritage sites and documents across Palestine, what are the steps RIWAQ is taking to protect its archives?

We are really facing a very difficult moment, because all our archives are in Jerusalem, and Jerusalem is not accessible to us any more.

So what do we do? How do we protect our archives? How do we protect our memory?

We need to find a way of scanning, digitising, making it possible to have more than one archive, so if one is lost, the other remains. For me, the biggest danger now is losing memory, because if you lose memory, you lose everything. That is the main concern.

Now, we started a new phase of trying to put all of our archives on iCloud, which is major work. The Israelis have thrown the equivalent of a nuclear bomb in Gaza, so it's not that simple to protect it.

We want to put this archive somewhere where physical destruction can't reach.

- Previous Article New Braille-Accessible Public Library Opens in Maadi

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites