The Life & Works of Surrealist Egyptian Poet Joyce Mansour

Focusing on themes of displacement, femininity, and desire, Joyce Mansour was described as “the most important writer in the Surrealist Movement.”

Originally Published June 26th, 2024

In her poem entitled ‘A woman created the sun’, Egyptian poet Joyce Mansour writes, “A woman created the sun/ Inside her/ And her hands were beautiful/ The earth plunged beneath her feet/ Assailing her with the fertile breath/ Of volcanoes.” This poem is, perhaps, a succinct introduction to the poet’s oeuvre- deeply concerned with the power of the feminine, and expressed in tones uncanny for her era, heritage, milieu and geographic location.

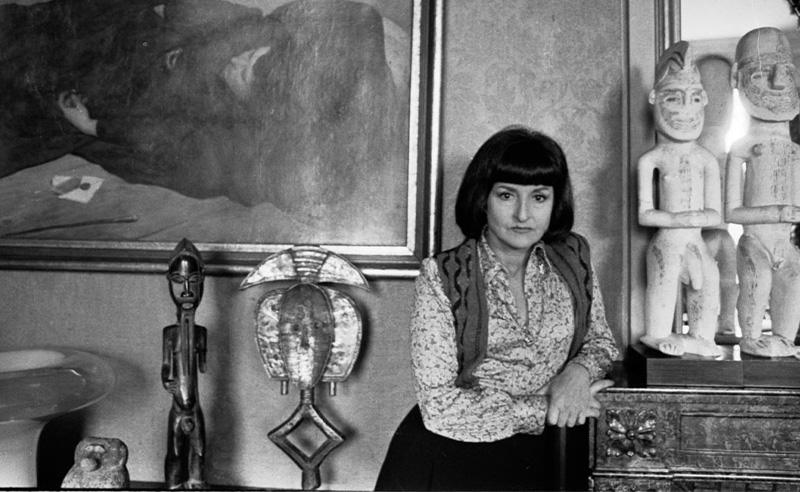

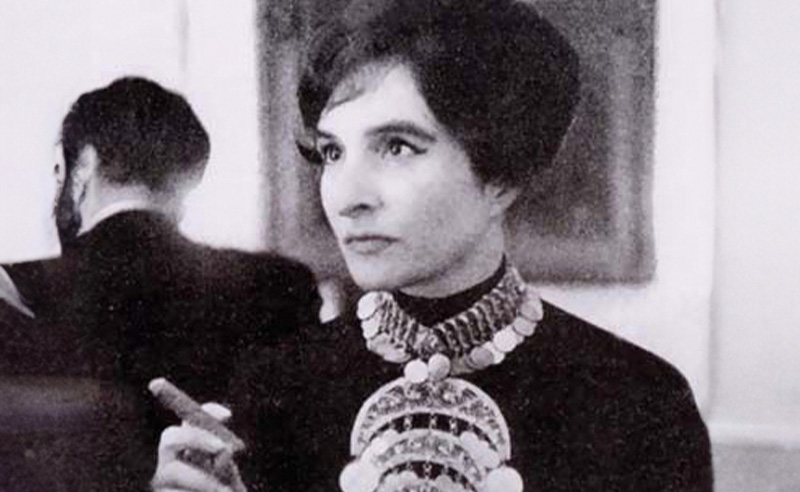

Born Joyce Adès in 1928 to Cairo’s grand Adès family, a cornerstone of Egypt’s Jewish community, the poet was born into a life of splendour, opulence and pomp. Deep, dark-set eyes and luscious brown hair falling low, a fashionable silhouette of avant-garde garb and exotic jewellery - the striking physical feminine mystique of Joyce Mansour belies the grand, loud, and profoundly melancholy poetry of the writer. Coming from the country’s financial elite with its orthodox mores, how then did Joyce Mansour become such a vivacious, unorthodox and surrealist poet, whose works focus very daringly on the subjects of female desire, eroticism, displacement and rage, in an epoch and class where such blatant expressions of femininity were viewed as taboo?

Emilie Moorhouse, translator of Joyce Mansour’s work from the original French to English in a recently published anthology of her works entitled ‘Emerald Wounds’, spoke to CairoScene about the poet’s fascinating life. Born in England and raised in a palatial residence in Cairo’s Garden City (which now houses the Greek Embassy in Cairo), Mansour at face value lived a gilded life, entrenched in the city’s upper classes. Describing the eminence of the Adès family, journalist Samir Rafaat wrote in an article documenting the haute-juiverie of old, entitled ‘Gates of Heaven’ which appeared in the Cairo Times in 1999, “...We run into the Mosseris, Suareses, Cattauis, Rolos, Adèsses, Hararis, Naggars, Cicurels, Curiels, Luzzatos et al. all of whom formed the pillars of Egypt's once powerful Sefardi community. Collectively the above families accounted for much of Egypt's banks, department stores, transport companies, and urban and suburban developments. In their debt also are two important museums: Bab al-Khalk's Islamic Museum and the Museum of Modern Art.”

The English-educated Mansour was a product of the elite, orthodox and esteemed haute-bourgeoisie of the Cairo of old. “Mansour had what could be considered a very proper and privileged upbringing. Part of her schooling was done in an English boarding school in Switzerland and for most of her childhood, even in Egypt, she had an English nanny. She seemingly had a very happy childhood growing up in Cairo, and would have wanted for nothing, until the death of her mother which affected her immensely,” notes Moorhouse. This personal tragedy would greatly affect the young Mansour, and ultimately turn the writer into a vanguard of surrealist poetry.

The death of Mansour’s mother and first husband during her teenage years drove the writer to expressions of grief in the form of poetry. “I am man/ Man who shoots the trigger and shoots emotion/ To live better,” reads a verse of her poem ‘I am night’. Commenting on the deaths of these two close family members in a 1977 interview, Mansour said, “I was a sportive girl in the sun until my mother died … then I got married. My husband died also. At that point I became conscious of all this and started to see things. One sees that everything is not rosy. I wrote to get it all out.”

During the presidency of Gamal Abdel Nasser and his Pan-Arabist and socialist policies, the Adès family along with the rest of Egyptian Jewry were subject to expulsion and sequestration. Mansour along with her second husband moved to Paris. She would never again step foot in her native land. “Her poetry often references her childhood home as a kind of lost city, one she longs for but that she can never return to. Like her lost mother, or first husband,” Moorhouse says.

Commenting on Mansour’s lifelong attachment to her heritage, Moorhouse comments, “She was a student of Arabic poetry and literature, and ancient Egyptian stories are frequently referenced in her poetry, even if they often appear in the context of reversals. Her Arab and Egyptian identities are very much intertwined in the work, but again, always shifting.” Although she found her place amongst the other Surrealist artists and writers which brought the movement to global acclaim, Mansour’s distance from her Egyptian-Levantine homelands (the Ades family hailed originally from Aleppo, Syria) was prominent in her works, often referencing ancient Egyptian goddesses and biblical female figures such as Miriam, the sister of Moses in her works. “Artificial Nice/ False perfume from the hour on the couch/ For what pale giraffes/ Have I abandoned Byzantium/ Loneliness sucks/ A moonstone in an oval frame” she writes in ‘Sun in Capricorn’ reflecting on her exile from her native Egypt, and the complexity of her being an Arab Jew in France at the time.

What fascinates in Mansour’s literary work is also the fact that although she was an Egyptian Jew who belonged to the world of Francophone Cairo, Mansour’s mother tongue was neither Arabic nor French, but English. While she came to fame through works that were written in French, Mansour only started speaking and writing the language after her marriage to her second husband, Francophone Egyptian Samir Mansour. “Mansour’s ability to seemingly defy gender norms also might be rooted in the language of Arabic poetry itself,” writes Marwa Helal in her article, ‘Egyptian Enigma: Joyce Mansour’, in Poetry Magazine. “In Arabic literature, gender tends to be fluid or even transcendent, disappearing into the oneness of the erotic, allowing the beloved to be addressed wholly and directly, and/or symbolizing the source of creation itself.”

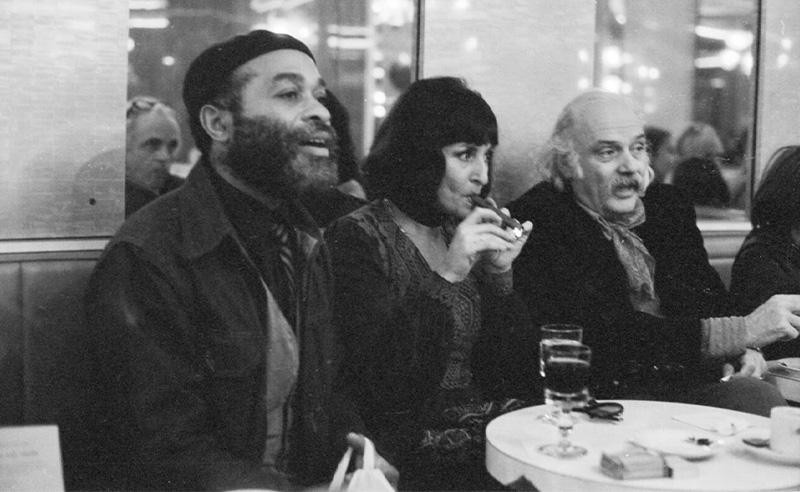

On the style of Mansour’s poetry, Moorhouse notes that, “Works of Surrealism were defined by unusual or unexpected juxtapositions, illogical or dream-like ideas of which Mansour’s work is full of. It’s clear that her work is a revolt against many social norms and expectations placed on her, especially as a woman.” The poet’s Parisian exile brought her right into the heart of the international Surrealist movement, where she became an intimate friend of the movement’s founder André Breton. Here, as she involved herself in the movement, Breton would name her the “most important poet in the Surrealist movement.”

Asked about the relevance of Mansour’s work in the modern day, Moorhouse says, “I was struck with the freedom with which Mansour expresses herself. She is not trying to please, on the contrary, she is speaking her truth, without worrying about how uncomfortable it might make people. I was captivated by her work, because even in 2017 when I first encountered Mansour during the #MeToo Movement. Hers was the kind of voice that had traditionally been dismissed, ignored, or downplayed as unimportant, too strange, or weird.” In our ever more globalised society, amidst our mixed-heritages, Mansour’s oeuvre speaks to a new generation of cosmopolitans. “The richness of her lineages, which she brings to her poetry, is reflective of our world. Increasingly, people today no longer live out their lives in a single place, often moving cities, or countries, sometimes multiple times, learning two, three or more languages. These aspects of her identity and poetry I think are incredibly relevant to our modern experience and reminds us that many of us have shifting identities,” Moorhouse says.

As of her death in 1986, Mansour’s oeuvre included 16 collections of poetry, as well as numerous works of prose. Today, the little known Surrealist poet is a symbol of both the lost literary cosmopolitanism of Egypt of yesteryear, and the modernity of feminine desire and emotion.

Once, asked about the importance of poetry in our world and culture, Mansour transported us back to the Egypt of her youth, commenting, “I went to the cemetery for a Muslim funeral. Suddenly a woman started to scream. The scream began, at first very deep, in the belly and became more and more shrill, deafening; it seemed to come from the top of the skull, you know, the fontanel, from which religions often say that the soul escapes at the moment of death. It’s terrifying. That is poetry. I write between two doors, all of a sudden, like that woman who started to scream.”

- Previous Article Immerse Yourself in Pure Serenity at Iridium Spa The St. Regis Cairo

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Mar 11, 2026