It’s Coming Home: I Returned to Morocco For AFCON 2025

The moment the fans landed at Tangiers airport for AFCON, I became a local, even when I didn’t know a single street name.

Wednesday 19th November, 2025

I hadn’t been back to Morocco since 2013, over half my life ago. When I arrived, an adult in my country for the first time, I found Tangiers to be something of an underwhelming city. Compared to Cairo, it seemed small, geriatric, and uncomfortably quiet. And I didn’t spot anyone that I fancied on the journey from the airport to our flat, so it seemed boring too.

Tangiers had been much more awe-inspiring when I was shorter, and younger, and more impressionable – when I had only seen Oxford, Oxford Street, and the Parisian countryside exactly once. The beach alone was enough to demand my respect, and I wasn’t yet old enough to be aware of my ostentatious Britishness in Morocco. I didn’t yet realise, at the time, the chasm of lived experience that existed between myself and my Moroccan counterparts.

When I was really little, we came every other summer or so, but by the time I hit double-digits, our trips petered out abruptly. I wasn’t conscious enough then to remember why, or to have asked why. We just got busy, I think. My parents’ cafe was providing a necessary service: the pensioners on the hill needed their oriental fix, and the students needed a cheap lunch. The neighbourhood needed cappuccinos and paninis and egg breakfasts and breakfast teas and carrot cake and ice cream and juice and shortbread, and suddenly, thirteen years had gone by.

Actually, I tell a lie. We did go back to Morocco once when I was 17, but we stayed squarely within the bounds of a resort in Marrakech for a week, just for some sun and some quiet, so I don’t think it counts. My parents chose a big Moroccan city for our holiday so that the smell of the air would be familiar, and they could easily create a rapport with hotel staff through their common language. We have no family in the city, so Marrakech was a comfortable, artificial extension of their Morocco, a proxy-home where they could still function on their own, but escape from the obligations of Oxford, Oujda and Tangiers.

I kind of understand that now. Returning to Morocco from a distance, I mean. In a way, I returned to Morocco via Cairo, and Cairo was my proxy-homeland for a time. In fact, being Moroccan in Egypt was somehow more satisfying – or at least easier – than my feeble attempts at being Moroccan in Morocco thus far. Despite the sinking feeling of not being taken seriously, of stumbling over my ‘g’ sounds and outing myself as ‘Maghribeya’ with every swallowed vowel, Egyptians never made me feel less Moroccan. My identity was never questioned in Cairo. Instead, I think it was reinforced, for the first time in my life.

In the UK, my Moroccan-ness was underexposed, watered down. I don’t look typically Arab or typically African. Nobody knows what ‘Amazigh’ means and I don’t act Muslim enough for it to register. Also, my name isn’t spelled out in Arabic in my Instagram bio, so how is anyone to know I’m not just Spanish?

Living in Cairo was my first experience of an Afro-Arab country like my own, where I had permission to be theatrically Moroccan, but no one was there to correct the ways in which I performed Morocco, or to out-Moroccan me. In Cairo, I was free to claim my country, boundlessly, to claim to be the most authentically Moroccan girl who ever lived, because there was no comparison and no competition – only fraternity.

Egyptians recognised that I was not one of their own, but my alternative North African heritage permitted me access to a kind of Egyptian personhood not of a tourist, for a time. And since it had been eleven years, then, since I had set foot in our Morocco, I searched for my country and found it in the dust, in the heat, and in the hospitality. Feteer reminded me of msmen and, in my mind, every elderly man in Wast el Balad with a bushy silver beard had a counterpart in the Kasbah of Tangiers.

I was supposed to be spending my year abroad learning Egyptian Arabic, which is still mediocre, because instead I spent the year basking in the feeling of being almost home. More than that, photographing everything and plastering Egypt all over my social media felt like proving to everyone who saw that I was, in fact, an Afro-Arab girl.

Being Moroccan in Morocco, however, is harder than being Moroccan in Egypt. When I speak, I feel as though people are laughing at me, out of the corner of their mouths or in the crease by their eyes. They’re not, but still I talk incessantly about my time in Cairo, and I exaggerate how good my Egyptian is, and how much I miss Egypt, just to distract from my shortcomings as a Moroccan girl. With every anecdote about Cairo, I think I am trying to demonstrate that I don’t need Morocco, but I do.

In Egypt, my identity was vindicated, but from the moment I arrived in the Kingdom itself, the illusion was shattered, and now my insecurities persistently trip my words and delay my cues. Suddenly, my culture feels like a costume, like dressing up in my mother’s clothes. The shoes are too big, the djellaba too long, and the makeup too heavy. Strangely, until AFCON began, the most Moroccan I had ever felt was next to the Nile.

Sunday, 21st December 2025 | Morocco vs Comoros

The commencement of AFCON 2025, then, came as a solution, a spell for the union of every shade of Moroccan across the world, and I had been promoted. Suddenly, the city was flooded with people who were variably less Moroccan than me, and being able to say that I lived here, if only for a short while, elevated me above tourist status.

The moment the fans landed at Tangiers airport, I became a local, even when I didn’t know a single street name, and I could barely describe the location of my flat to a taxi driver in terms he would understand. My ability to mumble in Darija, and to mind my business like nothing was unusual to me – and my Moroccan friends – immediately set me apart from the vacationing masses, and I was grateful. Finally, I was not a tourist in my country, at least until AFCON came to an end.

Sunday, 4th January 2026 | Morocco vs Tanzania

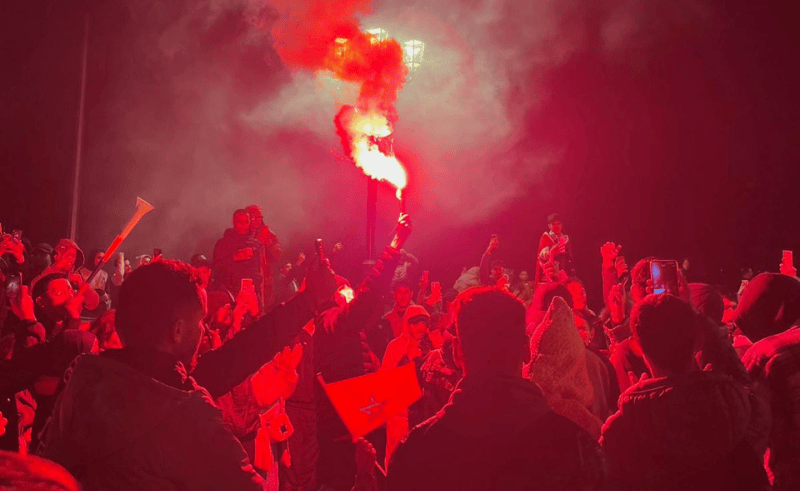

My mother texted me on WhatsApp immediately after the Morocco-Tanzania game: ‘This is your dream.’ And as the sound of honking began to rise all over the city, as it does after each football success, like a mistimed adhaan in ode to the beautiful game, I scoffed and showed my friend, Amine. Yet as much as I feigned ignorance and pretended coyly not to know what she meant, she was right.-b2f3996b-263e-4f04-9747-61f08f492b66.png) This was to me the culmination of years of unbelonging, learning and unlearning behaviours, and a pride in my country so fierce it threatened to tear me open from the inside out. This was my dream, to be in my country on the eve of our victory, and to celebrate like I was born here, and like I did know the street names.

This was to me the culmination of years of unbelonging, learning and unlearning behaviours, and a pride in my country so fierce it threatened to tear me open from the inside out. This was my dream, to be in my country on the eve of our victory, and to celebrate like I was born here, and like I did know the street names.

I suppose that is why, even by the end of the tournament, when the AFCON spirit faltered, gasped and died, I still feel lucky to have been here for it all.

Wednesday, 14th January 2026 | Morocco vs Nigeria

I watched the semi-final against Nigeria in Café Colon, equidistant from both the Grand Socco and the Petit Socco, and I felt similarly upon entering as I did any downtown establishment in Cairo. The walls, the open space and the pillars reminded me a little of Horreya - a slightly clinical, yet communal, atmosphere. There were 4 TVs, which each drew a sizable crowd of eyes, and ours drew a group of young boys in wool djellabas, tracksuits and trainers, who were disruptive throughout the game in a way that I found endearing only because the experience as a whole was so emotional for me.

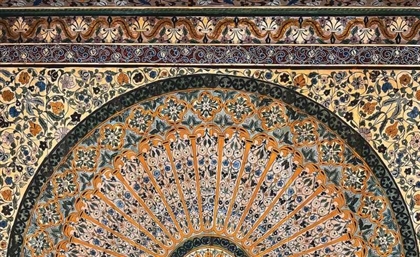

The game started at 9 pm, but we arrived at half past 7, when the space was already half full with men who scanned me up and down slowly. It’s difficult to express in words alone, but this was one of those locations that I used to picture when I thought of Morocco, drawn from distant memories and informed assumptions – a nameless place that the diasporic consciousness can imagine, but struggles to find.

I felt I had gotten close to this dream scene when I was in Egypt. I saw a version of Morocco that I remembered from childhood in the rows of quiet uncles in ahwas, the smell of stale smoke and coffee, and the acute sense that women were unwelcome there, derived only from their notable absence. Because of this, I found the feeling of being so intensely perceived upon entry to Café Colon oddly encouraging — a stamp of authenticity, as it were, that a diaspora kid feeds off of.

The rest of the seats in Café Colon were taken up by water bottles, ashtrays and packs of tissues, placed to reserve spots for men and boys who had run off to get food, pray or close up shop in the souk. The boys in wool djellabas kept gesturing to Natalie and Mariam, friends who had arrived later to join us, calling them ‘gawriya’ and asking if they spoke French. I was secretly so smug about that, having dodged the foreigner accusations by arriving early and sitting with Amine, who was so clearly Moroccan.

Now I am not an anxious person. I don’t tend to experience my stress physically; it doesn’t manifest outwardly in shaking or hyperventilation. Instead, I lose my appetite, or I am plagued by weird dreams. By the end of that game, however, I was weak. My hands and feet were tingling, and very little sensation remained in my fingertips. I had taken to gripping the table, or putting my hands in my pockets, taking small sips of water and nibbling slowly on a chocolate bar that I had found in the bottom of my bag for a sugar hit.

It was so bad that I really wasn’t sure if I’d be able to stand in celebration if we won, and by the third penalty kick, I was light-headed, performing deliberate breathwork, in and out on the count of three. Passing out in the cafe — as the ‘barraniya’ — would be difficult to recover from. Yet, while I was embarrassed by my bodily reaction to what was essentially a TV show, at the same time, I kind of revelled in it. It was almost like evidence of my authentic, personal investment in Morocco – undeniable and non-performative.

Looking back, I am uncertain whether I was shaking because of the stakes of the game itself, or because of the intensity with which I so desperately wanted to celebrate with my country again, and so desperately didn’t want my AFCON to end. Without the uniting force of another Morocco game, I would return to ‘tourist’, the unspoken bond that I had with the locals would dissipate, and the cultural chasm between us would reopen. I would be an outsider, again.

The final shot went in at 11.47 pm, securing Morocco’s spot in the final. I know the time stamp because I have videos and photos from almost every minute from then on until 1.24 am that same night. I reviewed them all and posted a minute-by-minute play-by-play on my Instagram, so that everybody could see what I saw. I took a thousand photos of the scenes, and occasionally forced myself to stop and squint and take a mental snapshot of my view. I knew that elation could impact my memory like drink, and the next day, I might struggle to remember the precious details.

Just before midnight, I bought Amine a vuvuzela, because he had left his at home, and his childish delight at the volume he could produce with that coloured trumpet could be matched only by a good boogie at the cabaret on a Friday. We walked en masse, all the way to the corniche by the sea, and when I sensed a fatigue come over me, or an impending irritation with the noise, or a pressing thirst for a drink, I reminded myself sternly that this was indeed my dream, and that I owed it to every version of me, past and future, to soak it up, gluttonously.

My time in Egypt had taught me to be cautious of taking photos of public spaces, not to be too brazen or voyeuristic in my documentation of the streets, and I had to actively shake off that instinct on this night, or I would have woken up the next morning with little evidence that I had lived it at all.

Sunday, 18th January 2026 | Morocco vs Senegal

Four days later, I took the train to Rabat to watch the final with my brother. I struggled for fifteen minutes to find my seat and space for my luggage, but eventually ended up tucked away at the back of a carriage, next to a man who was grading papers and found it difficult to keep his elbows to himself. Opposite me were two more men, one young and one old, both watching reels out loud and reacting minimally.

The journey took just under an hour and a half, and I met my brother at Rabat Agdal at around 1 pm. He had flown in from the UK the same morning, and come to meet me at the train station. We spotted each other, and simultaneously jumped to film the other’s reactions, so both of our videos are marred by the other’s phone.

It took well over an hour to make our way through the stadium to our seats, but we arrived just as the voices of almost 60,000 Moroccans singing the national anthem echoed through the venue. The crowd was red and flecked with green, and small subsections were highlighted in yellow. Only if you paused and focused your eyes could you make out the arms that waved the Moroccan Ultra flags from the wash of red behind them, and the singular Senegalese dancers from what appeared to be one yellow entity in constant sway.

The fans moved the same way, cheered the same way, watched every movement of the ball the same way, so I didn’t see the rupture coming. Until the 89th minute, there was an indomitable electricity in the air that turned to flame when the rain came, for even the sky started weeping in Rabat at extra-time. Perhaps the clouds foresaw the ending and sought to make it known that no good would come of dragging out this contentious match.

After the VAR decision, the walk-out, the violent clashes, the missed penalty, and the presentation of the AFCON trophy to the Senegalese team, my brother and I were two of very few remaining in the stadium. Though he had been born into football, I had been drawn to the game later in life by politics and nostalgia, so I honestly didn’t even understand the intricacies of play. I had come not for football, but for the love of a different game. I had come just to be there, at 23, to see it, document it, be part of it.

There was a sense in the lead-up to AFCON 2025 that this year would somehow be special. Throughout early December, each nation arrived, in stunning traditional dress, to assert themselves as individuals, but more so as part of a whole. Sudan and DR Congo came to show strength in spite of adversity, Egypt and Nigeria came to demonstrate fortitude and consistency, and even Morocco and Senegal played not for validation, but for dignity.

24 teams showed up to represent Africa, knowing that this year’s tournament would draw an unprecedented number of eyes from across the globe. Diaspora players – Mbaye, Diaz, Lookman – returned for AFCON, and I, too, had returned. We had all performed a pilgrimage to be there.

That is why my brother and I stayed longer in the stadium than most, until the cold became too difficult to manage. We were just as disappointed as the other Morocco fans, but win or lose, we felt lucky to have been present, so we stayed to soak up the last moments of the story, however much it had soured.

Yet in the hours and days after the wettest of walks out of the stadium, what stuck out to me the most was the rapid spread of a malice I thought only existed in jest – or deep in TikTok comment sections – which was in fact being broadcast freely on the internet, and in the streets. Debate about referee decisions and appropriate consequences very quickly devolved from shock and hurt into racism and vicious celebration. It made my heart ache to watch the spirit of AFCON dissipate so quickly, and with so little resistance from the masses.

Between Morocco, Algeria and Egypt’s reactions, the cracks in my Afro-Arab identity were clawed and torn open by the dramatic events of the final. How quickly we went from cheering with our Senegalese brothers at Sour Al Maagazine after the semi-final, chanting ‘Dima Maghreb! Senegal Rek!’ in tandem, wishing each other ‘Bonne chance!’ at kick-off, to turning on each other in the most despicable fashion.

In September, Morocco had been gripped by waves of 212 protests, by a generation of young people standing against the ultra-commodification of football; the co-option of a key cultural element while community and culture itself were relegated to the background. In a twist of irony, that is exactly what AFCON 2025 risks symbolising, precisely because of its controversial closure.

In this country, patriotic pride is so profound that, in spite of legitimate grievances, many who demonstrated in September could not resist the pull of the game. There were plans to boycott, but the draw was strong, to watch with one’s countrymen, and to celebrate as a nation not for an arbitrary victory, but simply for Moroccan success. Because of this, it is more upsetting still that while 2,400 protesters remain in jail across Morocco, lamentations revolve around a trophy and a penalty, and progress itself is overlooked.

The scale of AFCON expense necessitated an AFCON victory in Morocco to justify what had already been sacrificed at the altar of ‘the people’s game’. Though the score at the final whistle was 1-0 to Senegal, Morocco’s defeat felt deeper than a singular goal, because the journey to the final was so costly. It cost us momentum, and conviction, for a protest movement that may never stir again in the same way. Worse, AFCON buried demands for betterment, and the humiliating ending of the tournament left us only with questions of what could have been, had we not been distracted by a golden cup.

Such heat went into this AFCON, from all directions, that I suppose the final could only have been explosive, but the smoke is clearing, and we have yet to see if the house is still standing, or if the foundations have been irrevocably weakened by the flames.

- Previous Article Review: ‘Josephine’ Is a Sundance Breakthrough About Parenting

- Next Article The Middle Eastern Pulse of Leighton House