The Improbable Journey of Shady El Nahas from Egypt to WWE

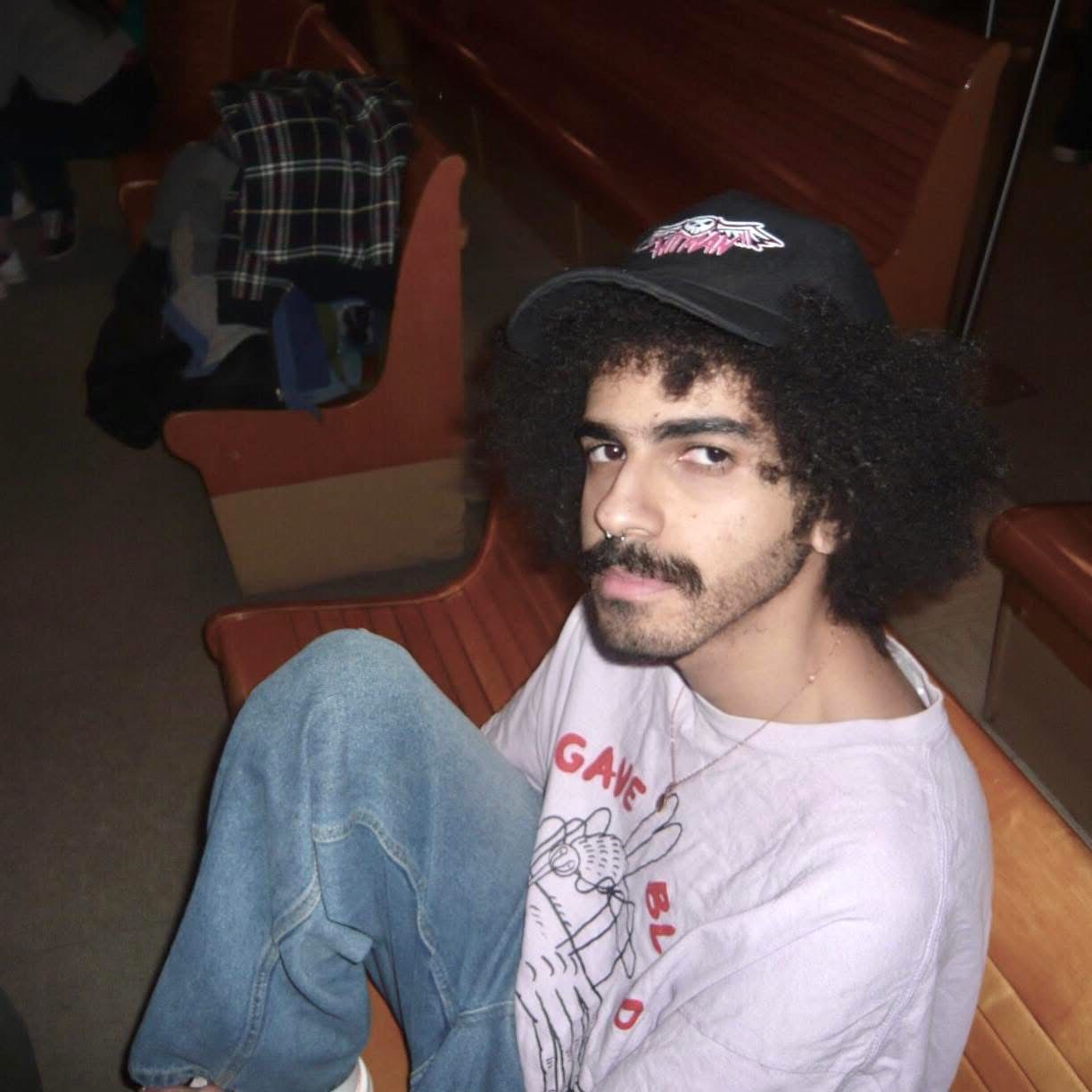

The Alexandria-born judoka reflects on his childhood, the weight of representation, and his journey to the world of WWE.

In May 2025, news broke that WWE had signed three Olympians to developmental contracts. One of which happened to be from Alexandria, Egypt, a city where wrestling once thrived on middle school playgrounds, pirated DVDs and posters taped to juice stands.

Among those shaped by that ecosystem was Shady El Nahas, who, to the untrained eye, might just seem like a two-time Judo Olympian with medals and international titles. But before all of that, he was something else entirely.

Back in the mid-2000s, those in the know in Alexandria recognised Shady as the kid who somehow got the newest, highest quality wrestling action figures long before they ever showed up in stores. The good ones - not the brittle, bootleg Luchadors with the backwards knees and the torsos fused to their pants. Shady had what could only be referred to as ‘the sacred stash.’ Toys that felt heavy in your hands. Nobody had a clue how he got them. Some said he had a cousin in the US, while others believed he made annual pilgrimages to the Dubai ‘Toys R Us’ and returned to Alexandria with a suitcase full of tiny plastic men, but no one could say for sure.

He wasn’t really a kid in the way the rest of us were. Shady El Nahas was an object of rumour and myth, an infrastructure, a blip in the supply chain. You did not meet him. You were sent to him. Like a mercenary in Carthage. “Try asking Shady,” the kids at school would whisper with their eyes darting like they were afraid of being overheard. “I heard he’s got the 2003 Survivor Series John Cena with the vest and chain.” And if, for whatever reason, the stars had aligned that day and you had something he wanted in return, he might’ve even been willing to trade.

When Shady and I finally reconnected on Zoom to speak about his journey, we couldn’t help but joke about the ridiculousness of it all. It was impossible to overlook the strange reality that Shawn Michaels, the wrestler he once coveted as a toy, had somehow ended up as his actual boss.

“I grew up watching WWE and Mamdouh Farag nonstop,” Shady said. “But back then, it always felt like there was no real way in. So getting here now... It’s kind of surreal. Like my childhood dream turned into my adult dream,” Shady tells CairoScene. He wasn’t alone. While wrestling was always in the air for a lot of kids in Egypt, saying you wanted to join the WWE was something you would often keep to yourself. There were no footsteps to trace or a path to follow. No one you could point to and say, “If they made it, maybe I can too.” The best you got were un-killable rumours that Batista was secretly from Kuwait, and that The Undertaker’s real name was actually Muhamed ‘Taker’ Abdulgabbar.

‘Training’ for many meant four sweaty boys on a trampoline, screaming made-up catchphrases while body slamming each other onto broken desks, tile floors, and whichever mattress your cousin dragged out that day. “After I got into judo, I moved to Toronto, then Montreal with my brother Mohab. I competed in the Olympics twice for Canada, and somehow that brought me all the way back to wrestling,” he says.“But like anything else, I still want to make a name for myself. Only here, I can be a little crazier and show more of my personality.”

The freedom to be expressive is part of the draw, especially considering how Arab wrestlers have historically been portrayed. For decades, WWE didn’t really know what to do with Arab characters unless they were villains or walking headlines after 9/11. A prime example was Muhammad Hassan, who, in 2005, was introduced as a frustrated Arab American wrestler dealing with discrimination. The irony was that the man playing him wasn’t even Arab. Before him, there was the Iron Sheik, a made-for-TV villain cooked up in the '80s to fuel postwar patriotism and cable news hysteria.

Progress, while visible in stars like the Syrian Canadian Sami Zayn, has mostly been symbolic. Structurally, very little has changed. Shady remains the only wrestler actually born in the region to sign a contract. And he hopes to change that.

“As soon as the Egyptian press found out I’d signed, my inbox blew up with people saying, ‘That’s my childhood dream,’” Shady recalls.

When I asked if he felt any kind of responsibility stepping into a space that’s never really made room for people like him, he didn’t hesitate. “That’s one of the first things I talked about when I got signed.” He meant representation, not just for himself, but for where he came from. Even after years in Canada, he still wants one thing to be clear: he’s Egyptian and always will be. “If it were up to me, I’d wrestle under my real name and speak in Arabic too,” Shady said.

He hopes that pride can carry over into things like his ring entrance and his overall presentation. When I put him on the spot and asked what Arabic song he’d walk out to in a perfect world, he laughed: 'Uhhh it wouldn’t be too crazy to come out to Mahraganat right?’ Then, with more certainty: “Has to be upbeat. Something exciting for the crowd and for me. Personality is a must.” “In judo, no one’s helping you,” he told me. “You’re working against someone. In wrestling, you’re working with them. It’s still your body, but the logic’s flipped. On paper, you’d think the switch to wrestling would be simple, but in practice, they couldn’t be further apart.” Judo comes with structure. There are medals. There is an Olympic ladder to climb. It is tough, but orderly. Success in the pro wrestling world can boil down to things like timing, presentation, and sometimes pure luck. You could do everything right and still end up buried under a dozen louder entrances and flashier moves. Still, this was the thing he’d been circling for years, whether anyone knew it or not. “You can’t necessarily celebrate in Judo the way pro wrestlers do, can’t do this or that, and you always have to be humble. Here, it’s the opposite. You’re encouraged to show personality and then some because it's part of the job.”

If judo taught Shady anything, it’s discipline. That’s what eventually won over his parents. More than the medals or the Olympics, it was the simple fact that he found something and stuck with something long enough to earn respect. If you come from Egyptian parents, you know that’s not nothing. The standard roadmap in the region usually ends with something closer to “doctor” or “engineer,” not a full-time wrestler who gets thrown through tables on live TV.

“They still want me to finish school,” Shady said. “And I probably will. Eventually. But this is my life now. I don’t want to just survive here. I want titles. I want people to say, ‘That Egyptian kid can wrestle.’ I want to be one of the best to ever do it.” There was a slight shift in his posture when he spoke this time. He sounded like he’d rehearsed this specific answer alone, almost like a kid eager for someone to ask the question so he could finally answer.

But the kind of success Shady keeps coming back to isn’t necessarily the kind you pin to a board or raise above your head. “More importantly, I want to help my family. If something good comes out of all this, I want it to go to them, not just me. They’ve supported me the whole way through, covered the travel, the judo tournaments, everything. It wasn’t cheap. I’ll always be grateful for that.”

Shady currently trains at the WWE Performance Centre in Orlando, Florida, with a potential NXT debut ahead on Netflix.

- Previous Article First Complete Canopus Decree in 150 Years Unearthed in Sharqia

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Feb 16, 2026