Third Culture Dating: Notes on Saying "I Love You" in Translation

Dating as a third culture kid is a masterclass in nuance. Throw in time zones, identity crises, and code-switching, and you’ve got a first date that feels like a cross-cultural case study.

How do you say I love you in three different languages?

In my mother tongue, Serbian, it arrives sideways: an offhand, half-scolding, half-tender, “Jel si smršala? Ajde da te nahranim” – “Have you lost weight? Come, let me feed you” – followed by a table full of meat, pies, and homemade things that take all day to make and 10 minutes to inhale. In English, it’s a throwaway line, light and elastic, something you tack onto the end of a call with a friend: “I love you, bye.” In French, it asks for a moment, a flowery, overdetermined declaration about love and life, words spilling out like sunlight speckled onto a grassy field.

There’s a name for growing up in that in-between. Third Culture Kids (or TCKs) – a term coined by US sociologist Ruth Hill Useem in the 1950s – are children who spend their formative years in cultures that are not their parents’ homeland. The familiar identity crises of “Who am I?” and “Where do I belong?” gets knotted up in a globalised world: parents forced to migrate in search of work or safety, transnational marriages, international schools in “home” countries where your mother tongue quietly slides into second or third place. The combinations vary, but the term helps name that feeling of being a synthesis of disparate things, forever navigating cultural cues and code-switching.

What happens when a Third Culture Kid goes searching for “I’m falling for you?”

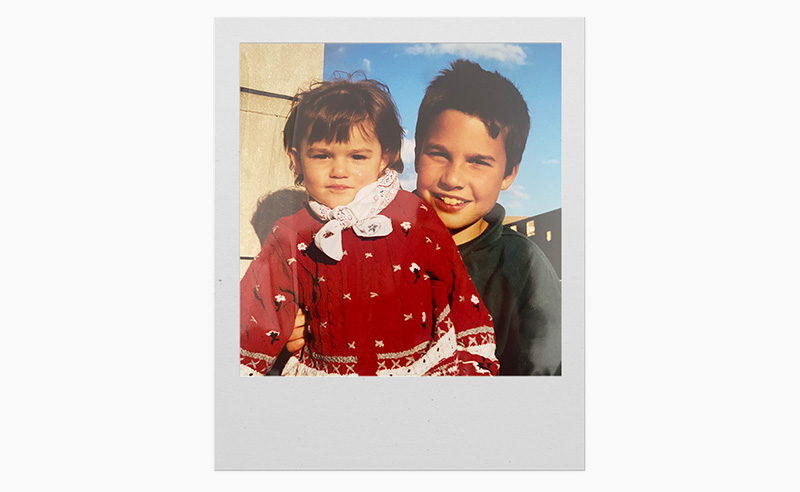

Growing up, my sense of self was always on a sliding scale of relativity. Both my parents are from Serbia; they arrived in the US during the war and the breakup of former Yugoslavia, determined to keep “home” alive in a place that wasn’t. I was born in America but was always known as European – the girl with the hard-to-place accent and funky hand-knit sweaters. In Serbia, though, my American lilt and lack of local pop-culture references gave me away within minutes. I belonged and I didn’t, in both directions at once.

I went to undergrad in France, my first time living away from both of my supposed homes. There, I was ambushed by the realisation that I was, in fact, American in ways I hadn’t allowed myself to admit; 18 years in one place (however reluctantly) had seeped into my cultural skin. Since then, I’ve traded cities with increasing ease – a brief escapade in Singapore, a couple of years in London, and now Cairo. When someone asks where I’m from, I take a breath and silently edit: How much do I divulge? Do I say Serbian first? Does American still count if I haven’t been back to visit in over three years?

In that hodgepodge of identities and “homes,” now add the task of trying to date.

Dating Someone Who’s Never Had to Translate Themselves

I was once on a dinner date with an American in New York and halfway through the appetisers I knew it was inevitable we wouldn’t work – even though seemingly he checked most of my boxes. He grew up in New Jersey, his whole family clustered between Jersey City and Manhattan. His plan was to stay in the city for a while, work that big finance job, then eventually move back to New Jersey near his parents and the familiar ring of aunts and uncles.

On the other hand, my parents are still deliberating whether to “go back home” or stay – a question that has been open ended for the last 30 years. My brother lives halfway across the globe, and most of my family is scattered between continents.

My date’s strong sense of cultural identity, and this solid, almost gravitational idea of where he wanted to build his life, felt at odds with my Frankenstein conception of self and culture. All my existential questions – where I belong, what language do I want to raise my kids in – felt like a behemoth next to his neatly packaged 10-year plan.

Maybe that says more about my own inability to reconcile my identity. Why should a partner have to share your exact qualms? But the more I’ve dated and met self-identified Third Culture Kids, the more I’ve found a shared, comfortable vocabulary that turns the crisis voice down to a murmur. There’s an unspoken understanding that most of my vacation days will be spent visiting family, that I will spend hours on the phone with long-distance friends, that navigating time zones and long-haul flights are not exceptions but the everyday texture of my life.

Love, From a Distance

Like most diaspora, I’d been training for that kind of distance since childhood. You learn early on how to build connection – and sustain love – through a screen.

I met my first best friend in the playground in front of my grandparents’ apartment. When the Belgrade summer visits ended – in that pre-WhatsApp, pre-social media era – as six-year-olds we continued to stay in touch by emailing from our moms’ AOL accounts. We’ve never lived in the same place, but those first emails, that then turned to Facebook messages, to now hour-long FaceTime calls have bound us so closely that no one who knows me doesn’t also know Sara.

A friend of mine met someone on a trip to London – one Bumble date turned into a week of dates and a free fall into love. Since both were raised in this patchwork of long-distance families, the idea of creating and sustaining love an ocean away didn’t feel wild; it felt possible. Another friend fell in love while visiting friends in Dubai. Even though he recently started putting down roots in another country, after living in five different cities, he had the muscle memory to pack up and go, and move to Dubai to see how the relationship would evolve. When you trade cities like place cards, “starting over” gets a little easier each time.

Although this is only possible due to a certain kind of privilege – the right passports, the money for flights, the freedom to “see what happens” – underneath that is a quieter philosophical shift that marks a lot of Third Culture Kids: nowhere feels fully like home. Every time you leave, there is always someone missing. Another move is just another line on the list of people and places you’ve left behind. And so moving for love, daring to start an early relationship an ocean away, feels easier – even familiar.

And there’s something strange and beautiful that happens in that type of life: the world seems to shrink. Long distance doesn’t feel like an obstacle to overcome; it feels like the default setting for how you love.

Finding Love Between Languages

When you live in various countries, I find that every place is a mirror to yourself, it exposes the calluses and scars and hidden strengths that only are unveiled in the unfamiliar. Just like places on a map of your life, each language you speak also carries its own emotional cartography, a set of instructions for how to love and be loved.

It opens up a doorway into different versions of yourself.

In English, I’m calmer, more nonchalant; it’s the ease that comes with speaking in a language that feels neutral, slightly at arm’s length from who I am. In Serbian, I’m softer, tugged back toward my grandparents’ bedtime stories and the warm blur of “home.”

I once dated someone who spoke both. With him, I could finally exist in those two selves at once. When the conversation turned political or academic, I could reach for the jargon and terminology I picked up in lectures and books. When we shifted to memories and jokes, I didn’t have to translate that one idiom that fit perfectly, or explain that cult song that defined my teenage years. The same went for him.

Another guy I met, he had that so-called international-school accent – a seemingly “neutral” English that actually signalled someone woven from many places. In front of strangers, he’d lean into a crisp British accent, a mask he’d learned to wear in Oxbridge circles to blend in and dodge the inevitable, “But where are you really from?” As he relaxed, the mask would slip: his Egyptian accent would surface, along with family stories and ridiculous childhood anecdotes.

Together, there was an ease in the way we moved between dialects. One that made it feel like my own tangle of languages and reference points could finally cohere into something – not a neat identity, exactly, but a shared mishmash of cultures that both of us understood.

Meeting the Family (Finally)

Then come the families. If you somehow make it through the minefield of modern-day romance and actually introduce a partner at home, a whole new set of obstacles appears. Dating as a Third Culture Kid is a masterclass in nuance. You need to know there are veiled parts of your partner’s identity, parallel lives they live depending on the room. You watch them laugh along when the table erupts, not because they fully understand the joke, but because they’ve learned to read the cues. You find yourself translating on the fly, softening edges, editing out comments. And running quietly underneath it all is the knowledge that, in some relatives’ eyes, you’re the one who “took” them away from their home country – and that one day you might also be the reason your children speak with an accent.

I had a friend once bring home a serious boyfriend for the first time, and this open, accepting version of her parents she had carefully curated in her head came crashing down. Deep-seated, internalised racism surfaced: “Is he going to try to convert you?” “What will people say?” “Have you thought about the children?” Suddenly she was code-switching at speed, softening their language in one direction, overexplaining his in the other, performing this impossible translation between the person she loved and the people she came from.

That’s the quiet tightrope of Third Culture dating: playing mediator between cultures, carrying your family’s fears and prejudices while trying not to let them dictate and shape your own desires. And in that complicated process it’s also giving yourself the space to mourn a vision of your parents you once had and the future they imagined for you.

Yet, that mourning clears a small patch of ground inside you – like a forest after a controlled burn – and in that charred space, new forms of love and belonging can start to take root.

A Third Culture of Our Own

What I’ve realised is that Third Culture has become its own kind of imaginary homeland – a third space where people who don’t sit neatly in any category can finally start to be themselves. When I date, it’s not about having matching passports, similar puzzle pieces, or an identical mix-and-match of cultures. It’s about finding someone who understands that home can be plural, and that grief and gratitude can coexist.

The question, I’m learning, was never really How do you say I love you in three different languages? It’s: what happens when two people, carrying their own scattered alphabets, sit down and slowly build a fourth one together. A language that borrows a Serbian idiom here, an English in-joke there, and a new, yet-to-be explored language imbued with overstatement for dramatic effect.

When I think of Third Culture now, I don’t just see the lonely child at the airport gate, or the teenager caught between cities. I see two slightly mismatched, Frankenstein dolls on a couch somewhere – hands touching, subtitles turned off – trying out phrases, gestures, and compromises until, almost by accident, they’ve made a small, portable homeland out of each other.

- Previous Article Dubai Chocolate's FIX Dessert Chocolatier Has Made a Mahalabia Bar

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Feb 16, 2026