From Nile-side markets to Libyan weddings, we follow the jalabiya’s journey across the Arab world and beyond.

From Cairo to Khartoum, Jeddah to Casablanca, long, flowing robes—whether galabeya, jalabiya, thawb, kandura, or djellaba—form a shared sartorial language across the Arab world. As universal, and as locally inflected, as the Arabic language itself.

The jalabiya may appear, at first glance, to be little more than a simple robe. But to call it that is to mistake a canvas for a sketch. Woven into cotton, linen, and wool, it is quite literally a fabric of history—practical and ceremonial, humble and ornate, a garment that embodies both uniformity and individual expression.

Its simplicity is deceptive. It speaks the language of geography, shifting subtly with climate: breathable fabrics and loose silhouettes in the Gulf; thick wool in Morocco’s mountain towns; delicate embroidery charting identity across Palestine. It signals class, gender, and place—women’s galabeyas in Egypt are sometimes cinched and flared, while Saudi men wear theirs stark and straight-lined.

Yet for all these distinctions, the jalabiya binds. Even in its most modest form, it carries weight: it absorbs the dust of history, the labour of daily life, and the stories of those who wear it.

This is an exploration of that continuity: from Cairo’s markets to Marrakech’s souks, Riyadh’s mosques to Libyan festivals, we trace the threads of a garment worn by men and women, across cities and villages, in everyday life and celebration alike.

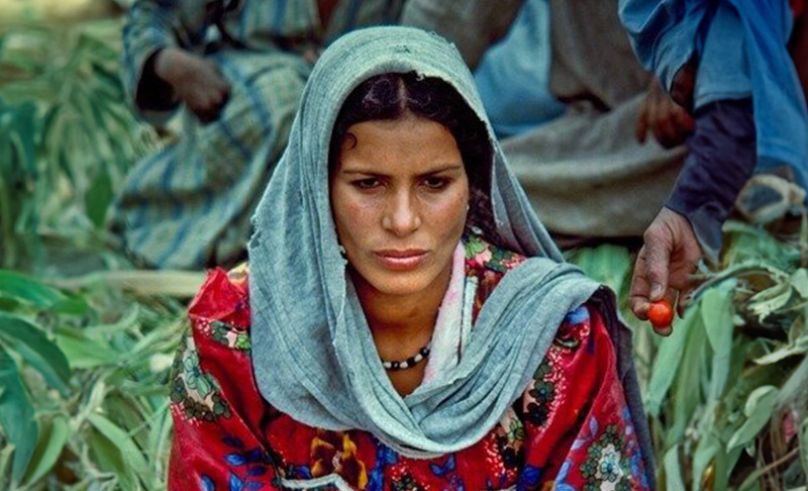

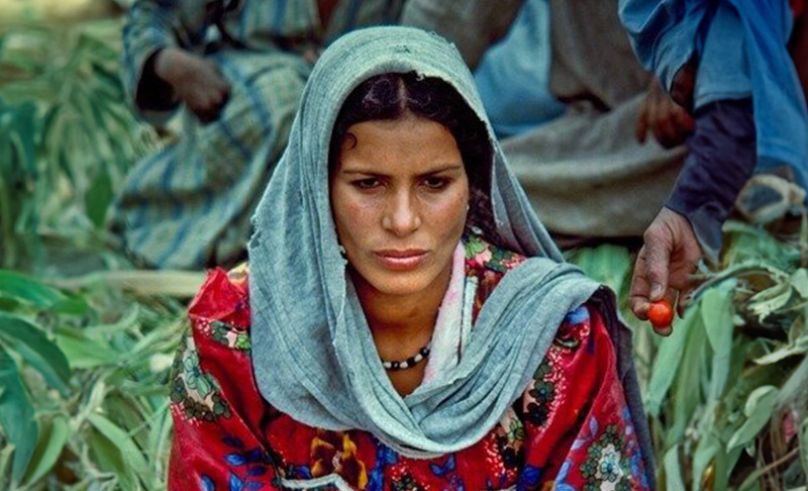

Egypt’s Galabeya

Image Source: Fine Art America

The galabeya has been a staple of Egyptian dress for centuries. Its roots can be traced to ancient Egypt, where loose-fitting linen garments were worn by both men and women for comfort in the heat.

Among its closest ancestors is the Coptic tunic of the 6th–7th centuries: woolen, flowing, and T-shaped, with rounded necklines and bold tapestry motifs. One such example is housed at New York’s Metropolitan Museum, a relic of Egypt’s late Byzantine textile tradition.

Today, men typically wear galabeyas that are straight-cut, pale in colour, and practical. Farmers wear them in the fields, Sufi dervishes during zikr, and elders to the mosque. The rural galabeya is marked by a wide, open neckline, often paired with an amamma (turban).

Women’s styles are more varied. The ‘galabeya bi wist,’ with its fitted bodice, flared skirt, and vibrant prints, has long been worn in rural Egypt—offering both function and femininity. The ‘galabeya bi sufra’ is looser, with a yoked construction and more relaxed fit.

Sudan’s Jalabiya and Toub

Photo Credit: UNEP

In Sudan, traditional dress reflects national pride and regional diversity. The jalabiya, worn by both men and women, is loose, ankle-length, and often white cotton—ideal for Sudan’s climate.

Men typically pair it with a turban (ammama), and depending on occasion or region, add layers: the jibba (outerwear), kaftan (undergarment), or sederi (vest). Women wear the toub—a vibrant, rectangular cloth wrapped around body and head. The fabric’s pattern, drape, and texture often reflect tribe, taste, and social standing.

Saudi Arabia’s Thawb

Photo Credit: Hassan Ammar

In Saudi Arabia, the thawb remains the foundation of men’s dress: ankle-length, crisp white, and tailored in cotton or polyester blends. Subtle variations in collars, cuffs, and buttons mark regional and personal style. Some include understated embroidery or tonal piping. It’s a daily uniform and formalwear in one—rooted in function, refined in detail.

The Emirati Kandura and Mukhawar

The Emirati kandura is similar in silhouette to the thawb but distinct in design. Collarless, with a rounded neckline and a signature tassel (tarboosh), it’s tailored for both heat and heritage. Sleeve and cuff variations indicate regional style across the Emirates.

Women wear the mukhawar, a traditionally modest home garment made from cotton or silk and heavily embroidered at the sleeves, hem, and neckline—often in gold or silver thread. Once reserved for domestic settings, it’s now worn on festive occasions such as Eid and Ramadan gatherings.

Morocco’s Djellaba

Photo Credit: Christopher Pillitiz

Across the Maghreb, men and women wear the djellaba—a hooded, full-length robe with wide sleeves and a pointed qob(hood). Wool versions are favoured in cold mountain towns, while lighter cottons suit coastal and desert heat.

Women’s djellabas are often brightly coloured and intricately embroidered with sfifa trim and ma’allem hand-stitching. Sequins or crystals may be added for weddings and holidays. For formal occasions, women may wear a belt (mdamma) and jewellery to elevate the look.

Tunisia’s Jebba and Sefsari

Tunisian men wear the jebba—a formal tunic layered over a shirt (chamîr) and trousers (sarouel), paired with a vest (farmla) and embroidered belt (hzam). Made of wool, silk, or velvet, the jebba is worn at weddings, religious festivals, and national ceremonies. Its elaborate embroidery reflects Tunisia’s hybrid of Ottoman, Berber, Arab, and Andalusian design.

Women traditionally wear the sefsari—a flowing white veil of silk or cotton, wrapped around the body and head as a symbol of grace and modesty.

Libya’s Farmla

Photo Credit: AFP

In Libya, traditional dress blends Mediterranean flair with Ottoman heritage. The jalabiya is worn daily by men and women—typically white, lightweight, and loose-fitting.

Men pair it with the farmla, a richly embroidered vest made of velvet or fine fabric, often decorated with gold or silver thread in floral or geometric motifs. The influence of Ottoman trade and aesthetics is evident in the patterns and craftsmanship.

Women’s attire is equally ornate: regionally varied robes layered with capes, silver jewellery, and embroidered belts—each ensemble a showcase of local artisanal heritage.

Palestine’s Thobe

Image Source: Fine Art America

While not technically a jalabiya, the thobe shares its structure: long, flowing, and layered with cultural meaning. For Palestinian women, it is a canvas of hand-stitched embroidery (tatreez), with motifs unique to region, status, and occasion.

Each stitch tells a story: thobes from Ramallah are marked by bold red cross-stitching; those from Bethlehem often feature fine gold and silver couching. Colours and placement are never arbitrary.

For men, the jalabiya remains a functional garment in rural areas—loose, breathable, and practical for labour. While increasingly rare in urban settings, it endures as part of the country’s living heritage.