Retracing Cairo’s Cat Culture

In many ways, the stray cats of Cairo mirror Egypt’s rapidly growing human population, resilient, adaptable, and constantly maneuvering through an ever-expanding metropolis.

Cairo is truly a city of paradoxes: ancient, modern, sacred, secular, bustling, and serene. One stands out among its many unique features: the city’s undeniable - and sometimes strained - bond with cats. These graceful creatures have wandered Cairo’s streets for centuries. They are revered and booted equally, and they remain a long-standing witness to this city’s ever-changing landscape.

In many ways, the stray cats of Cairo mirror Egypt’s rapidly growing human population; resilient, adaptable, and constantly maneuvering through an ever-expanding metropolis. Just like their human counterparts, Cairo’s cats carve out their own niches in crowded alleyways, bustling markets and historic landmarks, weaving themselves into the very fabric of the city.

Much like how humans in Cairo hustle for limited resources, be it space, jobs, or affordable housing, cats stake their claim on doorsteps, café chairs, and the occasional rooftop, establishing their own urban territories. Whether it’s a human struggling to navigate a traffic-choked street or a cat expertly slinking between cars, the same rules of survival apply: agility, street smarts and a bit of luck. And as Cairo expands both in infrastructure and population, so too do its feline inhabitants, multiplying at an outstanding pace.

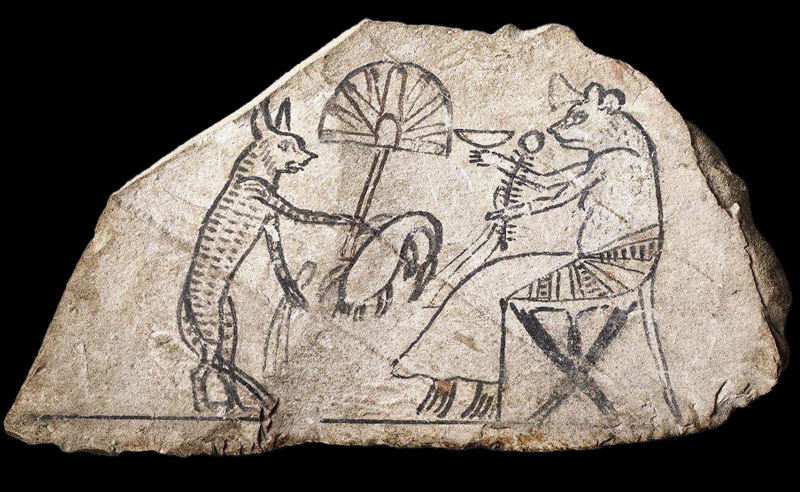

Cairo’s relationship with its felines has been forged through centuries of history. Legend tells that in times immemorial, the Egyptian sun god Ra - in the shape of an enormous cat known as Mau - fought against and overcame darkness manifesting itself as a powerful serpent, Apep. It's an ongoing cosmic battle between chaos and order, where the serpent of chaos eternally threatens to overthrow both humanity and the gods.

The goddess Bastet, often depicted as a lioness or a woman with the head of a cat, was where the feline’s place in Egyptian culture was first solidified. She is home, fertility, and protection; her temples were places of worship and reverence for humans and their feline companions. Killing a cat in ancient Egypt, even accidentally, was a crime punishable by death.

In the streets of ancient Egypt, cats were celebrated as symbols of protection and good fortune. The Book of the Dead equated the cat with the sun, reflecting its divine nature. Golden Nubian cats were seen as manifestations of Ra’s power and celestial grace. The domestication of cats likely began in Nubia, where they were regarded as bearers of luck and protectors of vital resources such as grain. As efficient hunters of mice, cats became indispensable to Egyptian households and granaries, and their role as guardians inspired countless tales, including the earliest stories of the war between the Toms and Jerries of the world.

Cats were cared for with exceptional devotion. They were groomed, bathed and anointed with fragrant oils. Food was apportioned to cats even during famines, as their lives were considered as important as human lives. Upon a cat’s death, grieving owners in ancient Egypt went to extraordinary lengths to honour their pets. Cats were embalmed and wrapped in fine linen perfumed with cedar oil. In the city of Bubastis, solemn funerals were held, with mourners shaving their eyebrows in grief. Objects, such as toys and milk bowls, were placed in cat tombs to ensure their comfort in the afterlife.

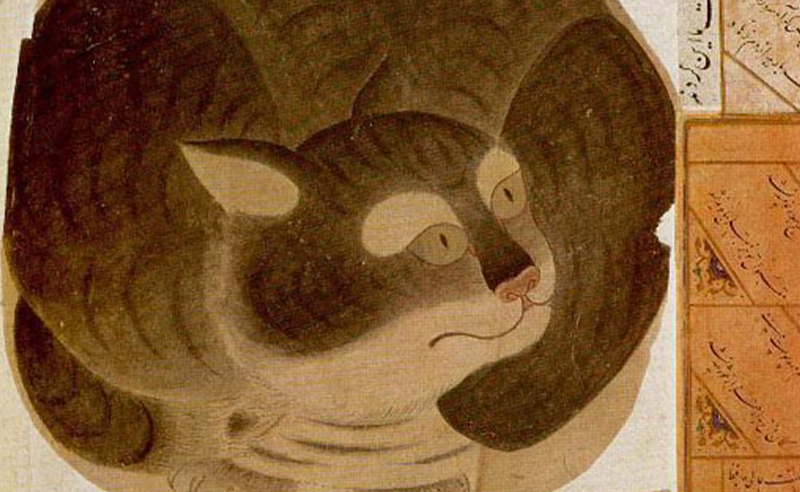

Lorraine Chittock, in her book ‘Cats of Cairo: Egypt's Enduring Legacy’, talks about how this reverence evolved through centuries. One of the most notable stories is the "cats' garden" endowed by Sultan Al-Zahir Baybars during the 13th century. This space provided food and care for Cairo’s stray cats, and the tradition endured for centuries. British orientalist E.W. Lane, writing in the 1830s, described his amazement at the daily gathering of cats in the High Court garden, where baskets of food were brought by the qadi (judge) to honour the sultan’s legacy. Despite the garden’s physical transformations over time, the endowment’s intent remained timeless.

Up to E. W. Lane’s days, the caravans of pilgrims going to the sacred precincts of Makkah from Egypt took a number of cats with them, though we do not know whether this was a reminiscence of the Prophet Muhammed’s (PBUH) love of cats, or the feeling that the gentle creatures might bring good luck. According to folk tradition, the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) cut off his coat sleeve because he had to get up for prayer and was loath to disturb his cat Muizza, peacefully sleeping on the sleeve; or how a cat gave birth to her kittens on the Prophet Muhammed’s (PBUH) coat, and he took care of the offspring.

Paradoxically, in Egyptian folklore nowadays, black cats are often seen as mystical creatures and sometimes haunted beings, one popular myth involves black cats and their association with Satan. In this tale, a black cat is said to transform into Satan himself at night, especially when walking through desolate streets. This association of black cats with bad luck is not rooted in Egyptian tradition but rather in European superstitions. In medieval Europe, black cats were linked to witchcraft and considered omens of misfortune. These beliefs were propagated by the Catholic Church, which, in the 13th century, declared black cats as incarnations of Satan. Such superstitions spread over time, leading to widespread persecution of black cats.

Today, many of Cairo’s mosques are known for their cat-friendly atmospheres. Al-Azhar Mosque, for instance, often sees cats sprawled across its sunlit courtyards. Some worshippers bring scraps of food for these creatures, viewing their care as an act of kindness (Sadaka). Cats’ presence in mosques is often welcomed, as they are seen as clean animals in Islamic tradition.

In the labyrinthine streets of Cairo, cafés often serve as unofficial cat shelters. Regulars at ahwas may recognise certain cats as part of the local scene, fed by patrons and staff alike. It’s not an untraditional view to see a cat perched on a café chair, surrounded by Cairenes engrossed in conversation.

In marketplaces like Khan al-Khalili and Attaba, shop cats are ubiquitous. These felines often reside in stores, sleeping on merchandise or greeting customers. Shop owners care for them, viewing them as good luck and valuable partners in deterring pests. Similarly, in neighbourhoods like Zamalek and Bab al-Louk, cats thrive along bustling streets, in local cafés, and even on the banks of the Nile, where they add charm to the scenic surroundings.

Despite their enduring and often welcomed presence, life for a street cat in Cairo is inundated with challenges. Hunger, disease and cruelty are everyday realities for many. Yet, amidst these struggles, a growing network of individuals and organisations is working tirelessly to improve the welfare of the city’s cats. Cairo's ongoing urbanisation has significantly altered the dynamics of human-cat interaction, as part of broader societal shifts tied to class and culture. In affluent areas, modern residential complexes, gated communities and high-rise apartments often restrict stray cats' access, distancing residents from the animals that once thrived in proximity. These spaces prioritise order and exclusivity, discouraging the informal care that stray cats traditionally received. Among the urban middle class, the perception of cats has shifted from communal creatures to status symbols, with pedigree breeds purchased as pets reflecting prestige. Stray cats, by contrast, are frequently overlooked or viewed as nuisances.

A critical figure in Cairo’s cat rescue scene is Nancy Essam, the founder of Cairo’s Cat Rescue and TNR Initiative. What began as a small effort in her apartment to house a few street cats has grown into a full project sheltering over hundreds of felines and dogs, with a particular focus on severe injury cases and accident victims.

However, her biggest challenge is debt. Running such an initiative independently, without governmental backing, requires significant financial resources. Veterinary bills, food costs and medical treatments quickly add up, yet she continues her work despite the financial strain.

Essam also highlights a grim reality; governmental veterinary services often take the easy way out when dealing with Cairo’s overgrowing cat population. Local authorities sometimes resort to poisoning cats or even having them shot by the municipality. “This approach is both cruel and ineffective, as eliminating cats in one area only results in another population surge elsewhere due to territorial shifts,” Essam tells CairoScene.

To counteract this, initiatives like hers focus on Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) programs. They capture street cats, have them spayed or neutered at their own expense, and then tag them before returning them to the streets. The government does not implement neutralisation programs due to high costs, leaving independent rescuers to take on the burden themselves.

Once a cat has been neutered and returned, Essam and her team work on educating the local community. “We tell the neighbours that these cats are good, that they won’t cause problems, they are now neutered and vaccinated and that they should be treated with kindness,” Essam says. Through a culture of understanding, her initiative hopes to reduce hostility toward Cairo’s cats and create a more sustainable coexistence between humans and felines.

- Previous Article WATCH: Ahmed Malek, Aya Samaha & Director Karim Shaaban on ‘6 Ayam’

- Next Article Six Unexpected Natural Wonders to Explore in Egypt

Trending This Week

-

Dec 23, 2025