A Photographer Returns to Cairo to Find What Memory Left Behind

In 'Re-discovering Home', Egyptian-Canadian photographer Fadi Salib traces a life split by departure and return, stitched together by rooms and streets.

Down a narrow Khan el-Khalili street, a microbus shudders into motion, its door swinging in hesitation. Someone jumps while it’s still moving half airborne, legs still inside. The light is thin, the focus is not behaving — but Fadi Salib presses the shutter anyway. Later he will look at the negative and smile at the smear of motion. “Technically, it failed,” he says. “But it told the truth.”

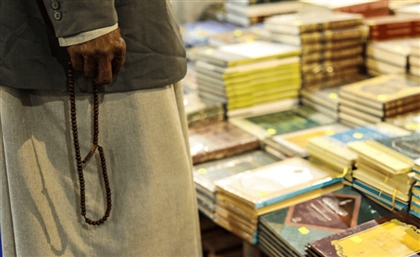

For Salib, truth has rough edges; it lives in the uneven frame, the steadying hand, the shadow beneath a balcony where gossip gathers in the afternoon heat. The up-and-coming Egyptian-Canadian photographer works between Cairo and Tkaronto (which is what he calls Toronto, Canada, referencing the original Indigenous name for the area). 'Re-discovering Home' — his ongoing body of work — records an oscillatory life split by departure and arrival, and stitched together by rooms, hands, streets and light. Through film photographs of family flats, cotton farms, seaside streets, and gestures of daily care, Salib builds a visual language of belonging — one assembled from memory, distance, and proximity.

“Home is a feeling,” he tells CairoScene. “When I’m in Tkaronto, I miss Cairo’s warmth. It’s a place of return, a place of belonging I carry within me until I’m able to be there again.” He was born in Kuwait, zig-zagged to Egypt each summer through his childhood, and trained first as an architect before settling on photography. The primary discipline stayed with him, though it’s grown more forgiving. “Architecture gave me a sensibility for composition and colour,” he says. “It’s the art of creating spaces that shape how people move, interact, and exist.”

In Alexandria, his grandmother’s flat feels as if it is caught in the resin of time. Terrazzo floors, cool underfoot; lace curtains, lifting with the sea breeze; a glass partition, cluttered with small miracles. A wooden boat, a glass fish, the faces of saints watching over it all. On the balcony, the old sabat is ready to descend for bread or tomatoes. “It’s where my father and his sister grew up,” he says, “and where I spent much of my time as a child. The smells from her kitchen, followed by the laughter of family gathered around the table, live inside me as reminders of my roots.” Sometimes the pictures are acts of retrieval: “I’m searching for memory, photographs that can transport me back to experiences that might one day disappear.” Sometimes they are first encounters, not recollections: “I’m also seeing parts of home I never knew deeply before, creating new memories. Those images become future portals.”

Salib's work is laden with Cairo’s unembarrassed volume, such as a shot of child in Lake Burullus, kicking water into glitter. “That photo feels like home,” he says. “Most of my memories are by water — the sea in Alexandria, or an inflatable pool in the backyard of my grandfather’s place in Agami. The smell of the sea in Alexandria always grounds me. Growing up outside Egypt, I’d return every summer, and that scent became one of the strongest reminders of my childhood.”

The pull of Cairo, Salib admits, has not been diminished by building a life elsewhere. “Geography creates distance, but it doesn’t erase belonging,” he says. “Canada has given me so much, and I’m grateful. But the warmth of my culture, of our people, is unmatched. As soon as I return to Egypt, belonging is instant; it floods back into me.”

Salib tempers that emotion with slower tools — a film camera, a darkroom, time in the age that promises infinite retakes and instant previews. For him, analogue seems stubbornly patient, the way Cairo is. “Digital makes everything too easy, and something gets lost in that ease,” he says. “Film, with its limits, teaches me to slow down and truly be in the moment.” He lights up at the mention of the darkroom — “the original Photoshop,” he jokes. “I’ve always gravitated toward hands-on, grounding activities — pottery, climbing. They quiet the mind. Film does the same.”

He is wary of the camera’s appetite. “If lifting the camera feels like it would break something fragile, I let it pass,” he says. “If it feels like the camera could hold the truth of it without interrupting, then it becomes mine to photograph.” It is a small rule of thumb, but it animates a responsibility to the scene, to the person inside it, to the exchange itself. “For me, curiosity and empathy fuel one another,” he says. “I may be physically outside the scene, but observing with empathy lets me connect and reflect. That makes me both an outsider and a participant at the same time.”

If his frames carry quiet, they are not mute; Cairo is NEVER quiet, not really. The city’s soundtrack runs through his sentences: “Waves, car horns weaving through the streets, neighbours calling out to each other just to say hi.” As a child, he slept on a bed on his grandmother’s balcony, those noises a lullaby. “Home would be the sound of chaos and aliveness,” he says. You can hear it in the pictures — the fist of traffic, a shout thrown across a stairwell, laundry performing for the wind. “What does home look like when it’s not romanticised?” I ask. “Arguments across balconies, the honking of traffic, laundry half-drying in the wind, kids yelling in the streets. It’s imperfect, chaotic, but alive.”

His architectural training gives him compositional muscle memory — sightlines, loads, planes of colour — but he distrusts over-control. The best pictures, he thinks, happen when thought loosens. “Most of the time, I try not to overthink,” he says. “I just follow my gut and let the photograph reveal itself.”

He was born in Kuwait, zig-zagged to Egypt each summer through his childhood, and trained first as an architect before settling on photography. The primary discipline stayed with him, though it’s grown more forgiving. “Architecture gave me a sensibility for composition and colour,” he says. “It’s the art of creating spaces that shape how people move, interact, and exist.”

In Alexandria, his grandmother’s flat feels as if it is caught in the resin of time. Terrazzo floors, cool underfoot; lace curtains, lifting with the sea breeze; a glass partition, cluttered with small miracles. A wooden boat, a glass fish, the faces of saints watching over it all. On the balcony, the old sabat is ready to descend for bread or tomatoes. “It’s where my father and his sister grew up,” he says, “and where I spent much of my time as a child. The smells from her kitchen, followed by the laughter of family gathered around the table, live inside me as reminders of my roots.” Sometimes the pictures are acts of retrieval: “I’m searching for memory, photographs that can transport me back to experiences that might one day disappear.” Sometimes they are first encounters, not recollections: “I’m also seeing parts of home I never knew deeply before, creating new memories. Those images become future portals.”

Salib's work is laden with Cairo’s unembarrassed volume, such as a shot of child in Lake Burullus, kicking water into glitter. “That photo feels like home,” he says. “Most of my memories are by water — the sea in Alexandria, or an inflatable pool in the backyard of my grandfather’s place in Agami. The smell of the sea in Alexandria always grounds me. Growing up outside Egypt, I’d return every summer, and that scent became one of the strongest reminders of my childhood.”

The pull of Cairo, Salib admits, has not been diminished by building a life elsewhere. “Geography creates distance, but it doesn’t erase belonging,” he says. “Canada has given me so much, and I’m grateful. But the warmth of my culture, of our people, is unmatched. As soon as I return to Egypt, belonging is instant; it floods back into me.”

Salib tempers that emotion with slower tools — a film camera, a darkroom, time in the age that promises infinite retakes and instant previews. For him, analogue seems stubbornly patient, the way Cairo is. “Digital makes everything too easy, and something gets lost in that ease,” he says. “Film, with its limits, teaches me to slow down and truly be in the moment.” He lights up at the mention of the darkroom — “the original Photoshop,” he jokes. “I’ve always gravitated toward hands-on, grounding activities — pottery, climbing. They quiet the mind. Film does the same.”

He is wary of the camera’s appetite. “If lifting the camera feels like it would break something fragile, I let it pass,” he says. “If it feels like the camera could hold the truth of it without interrupting, then it becomes mine to photograph.” It is a small rule of thumb, but it animates a responsibility to the scene, to the person inside it, to the exchange itself. “For me, curiosity and empathy fuel one another,” he says. “I may be physically outside the scene, but observing with empathy lets me connect and reflect. That makes me both an outsider and a participant at the same time.”

If his frames carry quiet, they are not mute; Cairo is NEVER quiet, not really. The city’s soundtrack runs through his sentences: “Waves, car horns weaving through the streets, neighbours calling out to each other just to say hi.” As a child, he slept on a bed on his grandmother’s balcony, those noises a lullaby. “Home would be the sound of chaos and aliveness,” he says. You can hear it in the pictures — the fist of traffic, a shout thrown across a stairwell, laundry performing for the wind. “What does home look like when it’s not romanticised?” I ask. “Arguments across balconies, the honking of traffic, laundry half-drying in the wind, kids yelling in the streets. It’s imperfect, chaotic, but alive.”

His architectural training gives him compositional muscle memory — sightlines, loads, planes of colour — but he distrusts over-control. The best pictures, he thinks, happen when thought loosens. “Most of the time, I try not to overthink,” he says. “I just follow my gut and let the photograph reveal itself.” What Salib tries to do in control the balance between openness and vagueness by being decisive at what stays in the frame. “Sometimes the chaos is the story, and the imperfections are what make it honest,” he says. “Other times, I strip the frame down to a single gesture or detail that carries the weight of everything.” He is equally decisive about what to leave behind: the pursuit of the seamless image. “Perfection doesn’t exist,” he says. “Chasing it means losing sight of why the photograph mattered in the first place.” The best encounters, he says, are the ones that relax into normality. "When a hand rests without tension, when laughter comes unguarded, when silence feels full rather than awkward.”

There are photographs that later surprise Salib by what they say not about the subject, but about the person behind the lens. “Images where people occupy the frame but I’m nowhere in it remind me how distance shapes my perspective, how absence can become its own subject,” he says. In that sense, his Cairo pictures double as self-portraits of a returnee: layered with joy, nostalgia, and the disorientation of belonging to two places at once.

“If someone called my work unfinished, that’s a compliment,” he says. “I don’t believe the work is ever ‘finished.’ The same logic applies to the notion of “emerging”, a word the art world loves because it implies a ladder. “To me, emerging isn’t a phase that ends,” he says. “It’s an ongoing process. I don’t think I’ll ever stop becoming something.”

What Salib tries to do in control the balance between openness and vagueness by being decisive at what stays in the frame. “Sometimes the chaos is the story, and the imperfections are what make it honest,” he says. “Other times, I strip the frame down to a single gesture or detail that carries the weight of everything.” He is equally decisive about what to leave behind: the pursuit of the seamless image. “Perfection doesn’t exist,” he says. “Chasing it means losing sight of why the photograph mattered in the first place.” The best encounters, he says, are the ones that relax into normality. "When a hand rests without tension, when laughter comes unguarded, when silence feels full rather than awkward.”

There are photographs that later surprise Salib by what they say not about the subject, but about the person behind the lens. “Images where people occupy the frame but I’m nowhere in it remind me how distance shapes my perspective, how absence can become its own subject,” he says. In that sense, his Cairo pictures double as self-portraits of a returnee: layered with joy, nostalgia, and the disorientation of belonging to two places at once.

“If someone called my work unfinished, that’s a compliment,” he says. “I don’t believe the work is ever ‘finished.’ The same logic applies to the notion of “emerging”, a word the art world loves because it implies a ladder. “To me, emerging isn’t a phase that ends,” he says. “It’s an ongoing process. I don’t think I’ll ever stop becoming something.”

- Previous Article Your Guide to GFF Screenings at Zawya Cinema

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Feb 12, 2026