Gaza’s Borderless Biennale Carries Palestinian Art Across the Globe

The Gaza Biennale could not happen in Gaza. CairoScene speaks to the artists living in Egypt about what it means to create in exile.

Originally published on November 14th, 2025

When the world turned their back on Palestine, the Gaza Biennale took matters into its own hands, circumventing the systems that failed them and forging their own path to global recognition.

The Biennale, as a concept, popularized by the bi-annual Venice exhibition that began in 1895, traditionally platforms international, political, and social dialogue through pavilions that represent individual nations.

Yet, despite the name, the Gaza Biennale has little in common with the Venice Biennale. It is not an art exhibition located in the place it is named for, nor does it occur bi-annually. The Gaza Biennale could not happen in Gaza, so it found homes across a dozen cities in the Middle East, Europe, the United States and counting.

In 2024, artists in Gaza and abroad collaborated with The Forbidden Museum of Jabal Al Risan in the Occupied West Bank to develop the Biennale and invite local and international institutions to host and produce the exhibitions.

The exhibitions, like many of the 54 participating Palestinian artists, are displaced. The artworks themselves are often not the originals, but printed reproductions or collaborations between the curators and the artists brought to life over Whatsapp calls. The artwork transcends physical borders when many of its artists cannot.

The recent Istanbul pavilion, “A Cloud in My Hand,” wrapped up in the beginning of November after hosting all 54 artists’ work in their nearly two-month long exhibition. Curators Shulamit Bruckstein and Reine Chahine discussed the process of bringing the physical artwork to life under dire conditions.

“It was very challenging because the artists don’t have internet all the time—maybe one or two hours per day, sometimes no electricity to charge their phones,” Chahine said. “But this project became a window to breathe—a source of joy and connection in the midst of war.”

The Gaza Biennale called collaborations like these “new rules of engagement within the context of art,” the organization wrote. “We are witnessing the failure of institutional frameworks to prevent the desecration of human life,” the Gaza Biennale team continued in an official statement. “From these cracks and disingenuous policies, we are stepping forward on our own accord, just as each artwork exists despite the impossible reality from which it is born.”

Of the 54 participating artists, the majority are still in Gaza. However, eight artists currently live in Egypt. CairoScene spoke with some of the artists living here in forced displacement, who spoke about the art they created for the Biennale after their arrival—artwork that is as much a representation of Palestinian identity as it is a search for themselves.

Motaz Naim, Beit Hanoun

But when the genocide began, he couldn’t continue painting. Beit Hanoun was one of the first areas targeted—the Israeli army forced Naim, his wife and children to leave their home immediately—and his studio. During the first month, they never stayed anywhere for more than a week, taking shelter in schools, health centers, and then a tent for over two months.

“Life itself was reduced to a struggle for food and water, “ he said. “There was no way I could work on art.”

Seven months into the genocide, Naim and his family crossed into Egypt through Rafah. As an artist, Naim has long focused on the relationship between people and their homeland, through impressionistic and expressive styles that highlight the beauty of Palestinian landscapes.

But when Naim started painting again in Egypt, he replaced his once colorful, joyful canvases with the horror he had just witnessed.

“There were martyrs, wounds, and ruins everywhere. Life became difficult, dangerous, and dark. I started portraying the painful scenes, the destruction, the gray and dark tones, using visual language to deliver a message to the viewer—to communicate our pain,” he said. “Most of my paintings now express destruction, loss, and the absence of memory.”

The Forbidden Museum contacted Naim early on while they were still developing the idea of the Gaza Biennale. He was excited to participate, and had already begun working on the collection titled “What Remains for Us”. Now, 13 of his original works have appeared in pavilions across the world, from Istanbul to Greece to London.

Naim felt that he had lost an integral piece of himself in those seven months in Gaza when he couldn’t paint. In Egypt, he returned to his craft with more energy and emotion.

“I felt it was my duty to express my people’s suffering—that’s the role of every artist, to stand with their people and contribute in their own way,” he said. “Through my art, I stay true to my craft and my people by spreading the Palestinian narrative—the narrative of truth and of injustice—to show the world that we are a people who deserve life.”

Ruba Hassan, Beit Hanoun-d3fc3b99-7557-41a3-9150-37e01a719054.png)

Ruba Hassan, 29, has lived in Cairo for the past year and a half. She and her family were displaced from Beit Hanoun, a city on the northeast edge of the Gaza Strip. They live with nine people in a single apartment.

Despite her training as a dentist, Hassan couldn’t find work when she arrived—the reality for many displaced Palestinians in Cairo who cannot obtain official residency in the country—and she wanted to do anything instead of thinking about the news coming out of Gaza. Painting and drawing had been her life-long hobby, and she thought that this could be a good way to occupy her time and her mind. So, Hassan bought art supplies.

But when she tried to put pen to paper, brushes to canvas, she felt guilty. Buying art supplies, let alone using them, felt like too much of a luxury as her friends and family in Gaza suffered under Israeli bombardment. It was a feeling she couldn’t shake no matter how hard she tried.

But when fellow Cairo-based artist Motaz Naim encouraged Hassan to apply for the Gaza Biennale, she thought, “Why not.” This could be an opportunity to use her art to give back to her community. Doing something was better than nothing.

As Hassan began to draw, she felt “renewed,” she said. Participating in the Biennale eased the weight of the survivors’ guilt she carries. Her goal was to show the world survivors’ raw emotions through symbolic representations of grief.

“More than just blood, numbers, and death,” she said about her artwork. “I want the audience to imagine themselves in the survivors’ shoes. If you were watching your own daughter die in front of you, what would you expect the world to do for you?”

Hassan created four pieces for the Gaza Biennale in a series titled ‘Anemones’, which has appeared in the Istanbul, Athens, and Sarajevo pavilions thus far, as printed reproductions, with Berlin coming soon. Before the Gaza Biennale, she had never presented her artwork in an official exhibition.

The blood-red poppy, or hanoun flower that is native to Palestine, draws a thread through the collection—a symbol of sacrifice, martyrdom, and memory. Another unifying motif is the circles that reflect time—life’s fleeting moments captured in the boundaries of its circumference. They double as clocks without hands, because time has stopped at that moment, Hassan explained—the moment when you cannot help your loved ones, and you are watching them die in front of you, or the moment you realize you have lived, and your family has not.

Hassan paused when she reached the painting of a boy staring down at a woman, his lips ajar. She is wrapped in a white shroud, hanoun flowers blossoming around them.

“The boy has stolen a moment in time to say goodbye to his mother,” Hassan explained, “because no one can say goodbye properly in war. The wind shows that time continues and life goes on, but the boy is stuck in that moment. He doesn’t understand that his mother is dead.”

Hassan’s eyes began to water.

“I lived this same moment,” she said. “My father was martyred when I was ten years old.”

She revealed that she was the boy in the painting. When her father died, she was too young and scared to understand. Hassan didn’t say goodbye; instead she climbed onto the roof of her house and, peering over the edge, only caught a glimpse of his body as they carried him away to his funeral.

“It’s been a long time,” she said of her father’s death in 2006, “but I still feel stuck in that moment.”

Mosaab Abusal, Al-Bureij Camp

Visual artist and graphic designer Mosaab Abusal flipped through the pages of his sketchbook, revealing one charcoal sketch after the next from his series on people seeking aid. Despite the black and white, abstract compositions, the theme was clear: children sleeping on the street, a makeshift “bathroom” built of a bucket and chair, a mother and daughter embracing in death.

Abusal was born in Saudi Arabia in 1988 and raised in the Gaza Strip, where he taught art as a university lecturer and UNRWA school teacher. In his past 16 years as an artist, he has participated in local and international exhibitions outside of Gaza. Abusal arrived in Egypt in May 2024 after being displaced several times at the beginning of the genocide with his elderly mother. They thought they would return to Gaza, but when Israeli bombardment intensified, it became impossible.

Abusal has lived in Egypt for over a year now. He has moved from house to house since arriving and doesn’t have the luxury of a stable art studio. But that hasn’t stopped Abusal from continuing his work, he said. “War itself gives an artist energy and provocation to create,” Abusal continued. “It tells you to keep working, to stay present.” He has adapted by using a digital drawing tablet and focusing on small-sized artworks that can be easily transported.

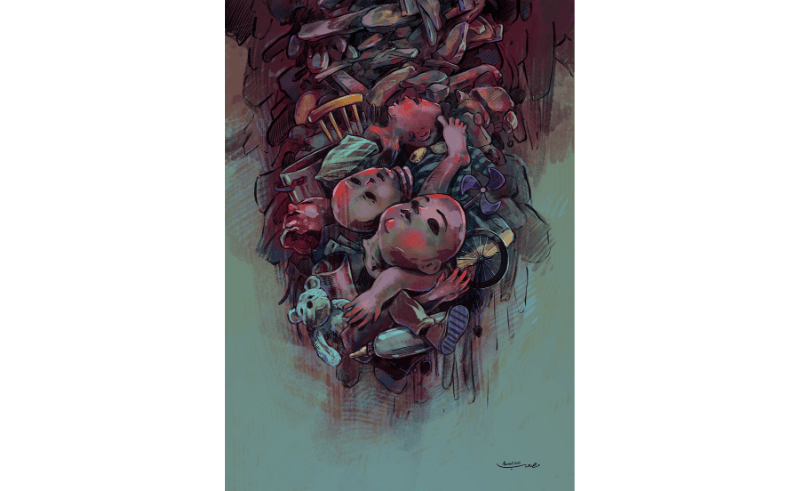

For the Biennale, Abusal created digital works titled “Nothing Survived My Room,” “My Remains in My Arms,” and “Voices Beneath the Rubble”—variations of which have appeared in places such as New York, Turkey, Italy and the UK.

Abusal draws to affirm, he said, to tell the stories that wouldn’t otherwise be documented. The scenes of mangled limbs and scattered homes are the images that have embedded themselves in his mind, and taken shape on his canvases.

Abusal has long focused on children in his work and used children’s toys to represent how innocence is disfigured by war. But this war—a genocide—was even more savage than previous Israeli assaults on the Gaza Strip, he said, “with a particular focus on exterminating children.”

In one of his main pieces, “Nothing Survived My Room”, doll heads, baby bottles, human limbs, and furniture hang in an upside-down mound—like shards glued together, forming one body. Disfiguration is a theme across his Biennale work, because in the genocide, “everything became distorted, fragmented, shattered,” Abusal said. “We’re narrating people’s stories under the Biennale’s name, so that these stories find people at their hearts,” he said. “I didn’t want my drawings to spark a political debate. Rather, I wanted to make people think about justice and humanity.”

Farah Qarmout, Tel al-Hawa

In one of his main pieces, “Nothing Survived My Room”, doll heads, baby bottles, human limbs, and furniture hang in an upside-down mound—like shards glued together, forming one body. Disfiguration is a theme across his Biennale work, because in the genocide, “everything became distorted, fragmented, shattered,” Abusal said. “We’re narrating people’s stories under the Biennale’s name, so that these stories find people at their hearts,” he said. “I didn’t want my drawings to spark a political debate. Rather, I wanted to make people think about justice and humanity.”

Farah Qarmout, Tel al-Hawa Artist Farah Qarmout contributed one piece for the Gaza Biennale. It was the first piece she was able to paint after seven months of living in Gaza during the genocide. In April 2024, she arrived in Cairo via the Rafah Border Crossing with her entire family.

When people asked her, “Why only one piece?” Qarmout said that she didn’t want to paint a series about continuous pain. She wanted a single painting “to convey a message directly from the heart to the viewer.”

Artist Farah Qarmout contributed one piece for the Gaza Biennale. It was the first piece she was able to paint after seven months of living in Gaza during the genocide. In April 2024, she arrived in Cairo via the Rafah Border Crossing with her entire family.

When people asked her, “Why only one piece?” Qarmout said that she didn’t want to paint a series about continuous pain. She wanted a single painting “to convey a message directly from the heart to the viewer.”

Qarmout’s piece, titled “Loss,” represents “the loss we suffer in war—but not the loss of hope,” she explained—the hope that the Israeli occupation tries to erase from the public consciousness.

Qarmout used timeless motifs of Palestinian identity and resistance to communicate this message, which she explained one by one, beginning with the diagonal that splits the scene into before and after the war. Before the war, the sea and sky are bright blue; the Great Omari Mosque, the Church of Saint Porphyrius, and the famous fishermen’s lighthouse stand intact. In Gaza’s Old City, a mosque’s minaret embraces a church tower; between them, a cluster of grapes cultivated from the land rests beside a cactus symbolizing Palestinian steadfastness, while a hand extends with a healthy green olive representing peace.

After the war, the olive has dried up. The hand is no longer extended in peace, but in a plea for food and water—the trees that once provided sustenance have been uprooted and burned. In war, one cannot even survive on the fruits of their own land. The skies have turned grey with ash and fire. Gaza’s ancient landmarks have crumbled under the weight of Israeli bombs; the mosque has lost its minaret, and the church its bell—echoes of a world that has lost its moral conscience. The proud, fruit-bearing cactus now bleeds, an assault on resilience itself.

Yet amid the ruin, one image endures. The orange peel in the sand, Qarmout continued, represents resurrection. “No matter how much they try to erase us, we remain,” she said. “Even if the orange fruit is gone, its peels remain on the ground—mixed with the red of blood and gray of earth.” Qarmout’s painting has been showcased in Italy, London, Sarajevo, and Istanbul. Currently on display in Cyprus, Berlin is set to host it next.

But this is only the beginning. In addition to the Berlin pavilion, the Gaza Biennale is heading to exhibitions in London, South Africa, Washington D.C., Lefkoşa, Padua, and Toronto. They are currently ongoing in New York City and Walla Walla.

As the Gaza Biennale artists navigate forced displacement within Gaza and abroad, their artwork, their stories, and their voices find homes around the world.

- Previous Article Saudi Retail Tech Firm Rewaa Closes $45 Million Series B Round

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Feb 12, 2026