Khalid Mezaina Turns Dubai’s Shifting Stories into Joyful Works of Art

Mezaina draws and stitches stories—part artist, part joyful observer of Dubai’s rhythm. His work dances between textiles, illustration, and pattern, guided by finding lightness in the ordinary.

The first thing you should know is that Khalid Mezaina is currently on crutches. This feels important, not as a piece of biographical trivia, but as a central, unwitting metaphor. The artist who loves to dance—for whom movement is a private, essential liturgy—has been temporarily grounded by a torn ligament. His immediate response was to design a pattern for the misfortune. This is the Mezaina doctrine in a nutshell: locate the rhythm, even in the stutter-step. Find the pattern in the pain.

Egyptian-Emirati artist Khalid Mezaina is a collector. This is true in the literal sense—T-shirts, comic books, the shared initials he has with Kylie Minogue—but it is the metaphysical collection that matters. He collects vanishing buildings. He collects the feeling of a city changing so fast the air itself seems to hum with the sound of one thing replacing another. He collects personal histories and prints them onto cloth, as if to give them a body, something to hold onto.

“I would like to think that my works tell personal stories and experiences about my context,” Mezaina tells SceneNowUAE.

From the early days of graphic design at Sharjah Art Foundation and Tashkeel to his MFA in Textiles at Rhode Island School of Design, Mezaina has worn many hats: designer, illustrator, print-maker. “My practice is a culmination of these overlaps and doesn’t necessarily fit any particular box,” he says. “I like that my works can be perceived as art, design or crafts because they are all of the above.” In this refusal to be pinned down, he perhaps finds his freedom.

His home in Dubai is his archive. It is a map of a mind that finds equal resonance in the textile souks of the old city, with their bolts of fabric that “have travelled from Africa and Asia,” and in the precise, mathematical beauty of Lebanese modernist Saloua Raouda Choucair, whom he recently illustrated for a children’s book. Holding that book for the first time was, he posted online, “quite joyful.” Joy for Mezaina is a discipline, a lens through which he filters a world he describes as “overwhelming.”

His home in Dubai is his archive. It is a map of a mind that finds equal resonance in the textile souks of the old city, with their bolts of fabric that “have travelled from Africa and Asia,” and in the precise, mathematical beauty of Lebanese modernist Saloua Raouda Choucair, whom he recently illustrated for a children’s book. Holding that book for the first time was, he posted online, “quite joyful.” Joy for Mezaina is a discipline, a lens through which he filters a world he describes as “overwhelming.”

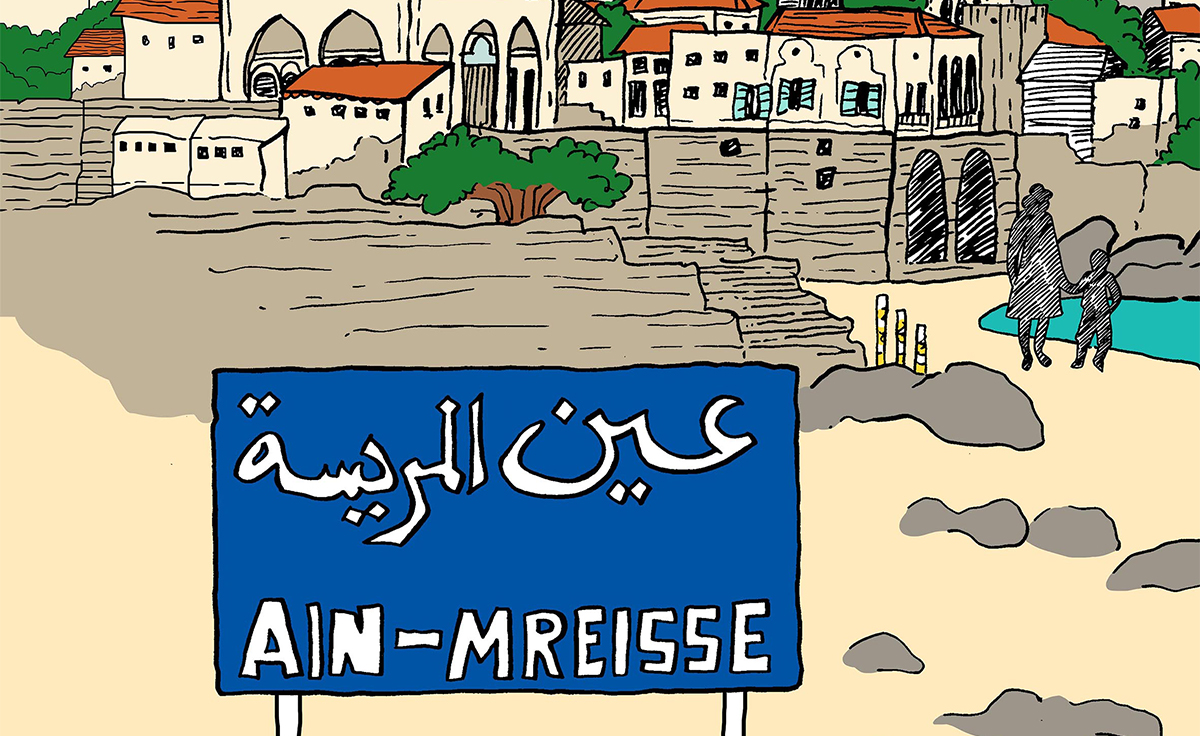

His work—a blend of illustration and textile art that he refuses to pigeonhole—feels like walking through this archive with him. A building he drew ten years ago might be a parking lot now, but in his lines, it remains, forever on the cusp of existing. He is not a preservationist; he is a chronicler. “I hope my works are some form of documentation of places and spaces that once were and are no more,” he says. He draws to acknowledge time’s passage, to give it a friendly wave as it goes by.

There is an early image of him—standing in a souk, mesmerised by the profusion of cloth, pattern, colour. He still returns there. “I’ve always been drawn to textiles. All these various textiles share stories and a visual language about where they come from…” And so the shift from paper to fabric is less a change of medium than a deepening of intent. A textile drapes, gathers, moves. It invites skin, touch, life. For Mezaina, drawing remains the starting point— “sketchbooks with drawings for different projects … pencil, ink, scan, develop digitally” — yet the hand-made remains essential. “Keeping a hand-made component allows me to not completely depend on digital devices,” he explains.

His work—a blend of illustration and textile art that he refuses to pigeonhole—feels like walking through this archive with him. A building he drew ten years ago might be a parking lot now, but in his lines, it remains, forever on the cusp of existing. He is not a preservationist; he is a chronicler. “I hope my works are some form of documentation of places and spaces that once were and are no more,” he says. He draws to acknowledge time’s passage, to give it a friendly wave as it goes by.

There is an early image of him—standing in a souk, mesmerised by the profusion of cloth, pattern, colour. He still returns there. “I’ve always been drawn to textiles. All these various textiles share stories and a visual language about where they come from…” And so the shift from paper to fabric is less a change of medium than a deepening of intent. A textile drapes, gathers, moves. It invites skin, touch, life. For Mezaina, drawing remains the starting point— “sketchbooks with drawings for different projects … pencil, ink, scan, develop digitally” — yet the hand-made remains essential. “Keeping a hand-made component allows me to not completely depend on digital devices,” he explains.

In his studio, this philosophy becomes physical. He talks about screenprinting with the passion of a scientist who has just discovered a beautiful, replicable flaw. He loves “engineered” patterns, ones he creates spontaneously on the printing table, free from a rigid grid. “Engineered patterns don’t need to follow a grid system,” he explains, “and can be as dense and chaotic or minimal and harmonious as you like.” The resulting textiles are sumptuous, layered things that feel alive in your hands—a quality he fiercely protects in a region, and an industry, that is “digital-heavy.”

Perhaps the most telling piece in his recent portfolio is the series 'Deep In D.A.N.C.E. 1‑30' (2023): 30 relief prints, each a dance of line and colour, each an echo of rhythm in ink. The title suggests movement; the work mirrors it. In a way, the series becomes a mirror for him: he is the dancer, the hoarder, the drawer, the city observer.

In his studio, this philosophy becomes physical. He talks about screenprinting with the passion of a scientist who has just discovered a beautiful, replicable flaw. He loves “engineered” patterns, ones he creates spontaneously on the printing table, free from a rigid grid. “Engineered patterns don’t need to follow a grid system,” he explains, “and can be as dense and chaotic or minimal and harmonious as you like.” The resulting textiles are sumptuous, layered things that feel alive in your hands—a quality he fiercely protects in a region, and an industry, that is “digital-heavy.”

Perhaps the most telling piece in his recent portfolio is the series 'Deep In D.A.N.C.E. 1‑30' (2023): 30 relief prints, each a dance of line and colour, each an echo of rhythm in ink. The title suggests movement; the work mirrors it. In a way, the series becomes a mirror for him: he is the dancer, the hoarder, the drawer, the city observer.

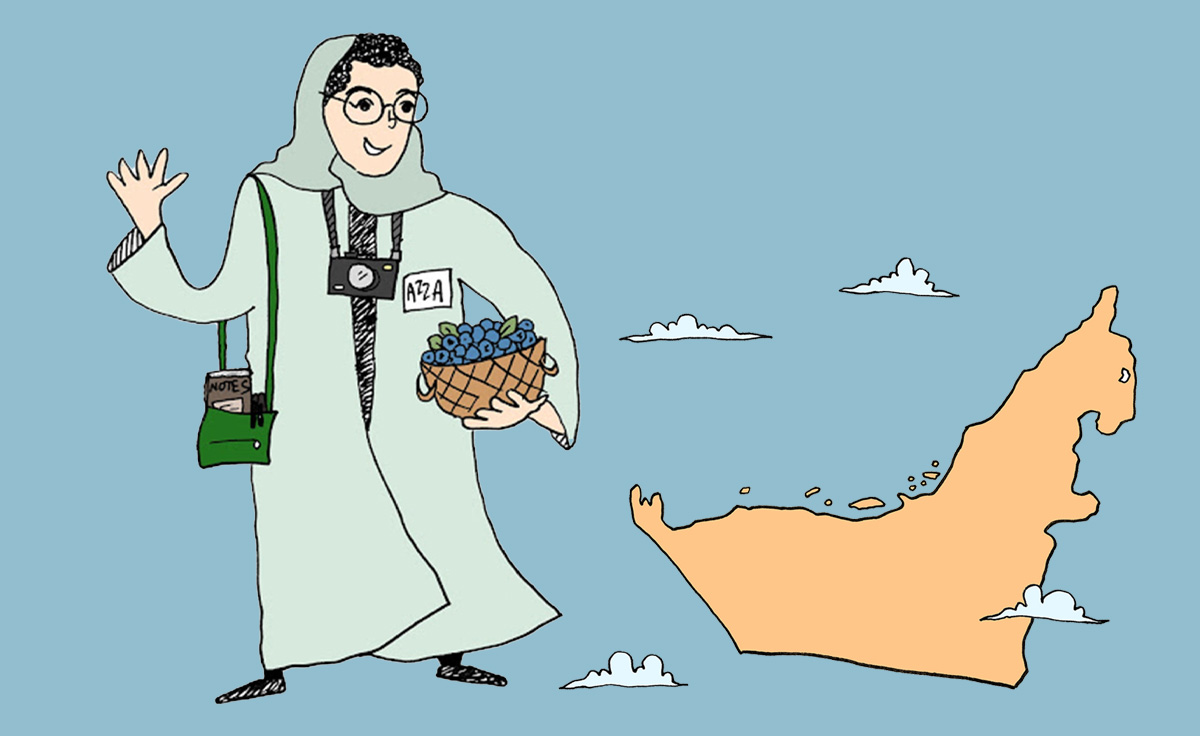

This insistence on the handmade is his quiet rebellion. It is also what makes his foray into the prestigious architecture biennale in Venice, where he illustrated research on UAE farms and food systems, so revealing. His drawings of greenhouses and irrigation systems were portraits of the structures that sustain life, rendered with the same affectionate line he uses for a favourite T-shirt.

And then there is his position in the art world, or perhaps just slightly adjacent to it. He is both recognised and something of an outsider. “I don’t think I tick particular boxes,” he says, a statement delivered with the clarity of someone who has taken his own inventory and is pleased with the eclectic results. He has made peace with working at the periphery. “That was my moment of liberation,” he says. And from that periphery, he has built an audience that seeks him out for exactly what he is: a storyteller who works in thread and ink.

This insistence on the handmade is his quiet rebellion. It is also what makes his foray into the prestigious architecture biennale in Venice, where he illustrated research on UAE farms and food systems, so revealing. His drawings of greenhouses and irrigation systems were portraits of the structures that sustain life, rendered with the same affectionate line he uses for a favourite T-shirt.

And then there is his position in the art world, or perhaps just slightly adjacent to it. He is both recognised and something of an outsider. “I don’t think I tick particular boxes,” he says, a statement delivered with the clarity of someone who has taken his own inventory and is pleased with the eclectic results. He has made peace with working at the periphery. “That was my moment of liberation,” he says. And from that periphery, he has built an audience that seeks him out for exactly what he is: a storyteller who works in thread and ink.

So what is the through-line in Khalid Mezaina’s collection? What is the grand theme? It is the stubborn, radiant insistence on a personal truth. It is the belief that a story about a lost building or a Lebanese artist or a torn knee ligament, when told with enough specificity and heart, becomes universal. It becomes a map for someone else.

“I hope people find some sense of joy when they encounter my work,” he says. “Even if it’s just a smile.”

The world is a loud and often traumatic place. Khalid Mezaina is in his studio, building a sanctuary out of lines, one joyful, collected thing at a time. He is building it for himself, and he is leaving the door open for the rest of us.

So what is the through-line in Khalid Mezaina’s collection? What is the grand theme? It is the stubborn, radiant insistence on a personal truth. It is the belief that a story about a lost building or a Lebanese artist or a torn knee ligament, when told with enough specificity and heart, becomes universal. It becomes a map for someone else.

“I hope people find some sense of joy when they encounter my work,” he says. “Even if it’s just a smile.”

The world is a loud and often traumatic place. Khalid Mezaina is in his studio, building a sanctuary out of lines, one joyful, collected thing at a time. He is building it for himself, and he is leaving the door open for the rest of us.

- Previous Article Museum of Natural History Abu Dhabi Opens With Meteors

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Feb 16, 2026