Designing Collective Utopia in Nasser’s Egypt & Tito’s Yugoslavia

How modernist architecture gave form to the shared dreams of Egypt and Yugoslavia during the era of the Non-Aligned Movement.

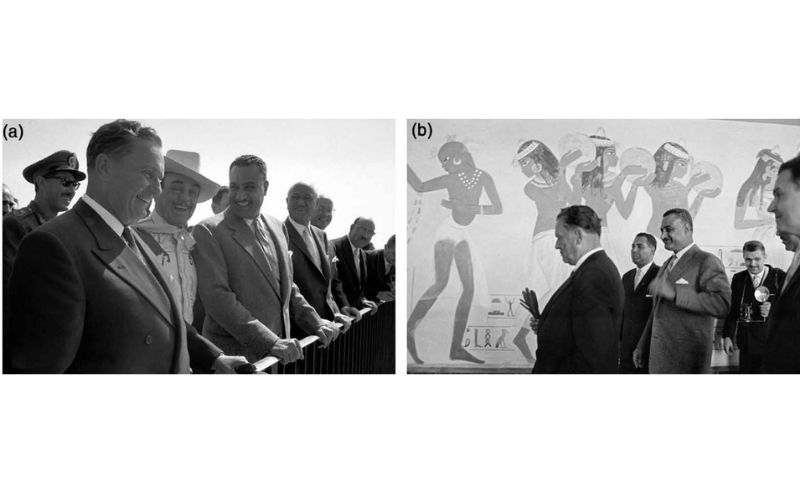

An archival photograph from 1959 captures an improbable intimacy. In it, Gamal Abdel Nasser stands shoulder to shoulder with Josip Broz Tito, Former President of Yugoslavia, and Conrad Hilton, President of Hilton Hotels, in his emblematic cowboy hat. The occasion is the opening of the Cairo Hilton, where a new form of modernism rises on Nile’s edge, with hieroglyphics sketched on the facade.

American capital, postcolonial ambition, and socialist leadership converge in a single frame, holding together contradictions that history would later insist were irreconcilable.

-83f1b0e8-6afe-4161-9f46-c9a31f90c213.jpg) Hilton Hotel exterior, 1959

Hilton Hotel exterior, 1959

-c54a54ec-19cf-4332-82ec-ec6c166d5c39.jpg) Hilton Hotel Advertisment

Hilton Hotel Advertisment

By its very design, the Cairo Hilton operated as a diplomatic object. Set beside Tahrir Square as Egypt rewrote itself in the wake of the 1952 Revolution, the project was commissioned to break from the neoclassical designs of British colonial rule.

Architecture became a tangible manifestation of a dream of an emerging nation.

The ‘Third Way’ of the Non-Aligned Movement

1959 is also a poignant time in history. During the apex of the Cold War, Nasser and Tito shared more than a passing political alignment. Each refused to be collateral damage between the Capitalist West and the Communist East. That language crystallised in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), during the Bandung Conference in 1955 together with world leaders coming together from Yugoslavia, Egypt, India, Ghana, and Indonesia.

-c0b96ecf-3576-46a2-9fe7-b6ad9716488d.jpg) World leaders Shri Jawaharlal Nehru of India, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Sukarno of Indonesia and Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia at the Bandung Conference in 1955

World leaders Shri Jawaharlal Nehru of India, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Sukarno of Indonesia and Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia at the Bandung Conference in 1955

Together, they set out to protect the interests of countries that didn’t want to be pulled into either the American or Soviet camp, pushing for sovereignty, neutrality, and cooperation between newly independent nations. It was also a moment when the world was shifting fast: across Africa, wave after wave of states were breaking from colonial empires, and pan-Arab politics were rising in the Middle East.

The Non-Aligned Movement offered a “Third Way” through that split world, building new routes for trade, expertise, and cultural exchange that didn’t have to pass through Western capitals.

At first glance, Yugoslavia can seem like an odd member of that club. But Tito argued that his country belonged there precisely because it understood what it meant to be held back and spoken for. After over five hundred years under Ottoman rule, and long treated as Western Europe’s ‘orient’ (an exotic other territory between East and West), Tito framed socialist Yugoslavia as proof that a nation once considered “backward” could modernise on its own terms. On a NAM trip to Guinea in 1961, he stated that Yugoslavia is “an example of how a country, enslaved and underdeveloped in the past, is able to rise” – positioning its project not as European, but unmistakably postcolonial.

Architecture Manifesting A Dream

Often described in geopolitical terms, Non Alignment Movement was equally a spatial project. Conferences required halls, intercultural solidarity required hotels, and sovereignty demanded ministries, housing, and infrastructure. In the following years, through NAM cooperation, Yugoslav companies were hired to execute ambitious infrastructure projects, including dams, railways, and roads across Africa and the Middle East.

Egypt and Yugoslavia – unlikely twins – became bound together as leaders bypassing Western gatekeepers of taste and expertise.

Tito’s Yugoslavian Brutalism

-6a5b1c59-ee16-47e3-8ab0-e1dce0a141ff.jpg)

Brutalist concrete, so often read as severity, instead was a means to manifest this socialist dream. In Yugoslavia, this ambition found fertile ground in Belgrade, particularly in New Belgrade, a vast expanse of mass housing blocks conceived almost from scratch. Here ideological aims of class equality were translated into affordable mass housing, generous public space, and civic institutions embedded into everyday life.

Each block of buildings was constructed explicitly around the hums of collective life. Repetitive windows and perpendicular lines became symbols of equality, and residential blocks socially engineered proximity and unity. From balconies facing inward, parents said their goodbyes as streams of kids headed to the green spaces inside, where a kindergarten, a playground, and sports field sat at the centre. There was no need for long commutes or for school districts; communal spaces were woven into residential blocks, collapsing the distance between private life and public belonging.

-225bae02-10b1-4555-9d06-aecf6c371531.jpg) New Belgrade, Serbia

New Belgrade, Serbia

The new approach to design was orchestrated by Yugoslav architects, liberated from the dictates of socialist realism architecture after Tito’s break with Stalin. Instead they were able to draw freely from both Eastern and Western modernist currents. This openness was reinforced by Yugoslavia’s unusual position during the Cold War, supported economically by the United States even as it remained socialist, a paradox mirrored in that Cairo Hilton photograph. The same ideological flexibility that allowed Tito to navigate global power blocs enabled architects to experiment across them.

Nasser’s Egyptian Modernism

During the Non-Alligned Movement, Yugoslav companies executed various infrastructure projects across the region including Iran’s Babylon Hotel and the emblematic Kuwaiti tower. However, Egypt’s modernist project unfolded differently, shaped largely by local architects.

Nasser’s administration sought to distance the nation from both colonial rule and selective readings of its own past including Greco-Roman and Islamic architecture. Instead modernism spotlighted the use of solid concrete and efficient standardisation.

Tahir Square From Colonial Playground to Modernist Future

Alongside the Hilton hotel, as a means to obliterate from colonial rule, the British Residence and the British army barracks were demolished. The surrounding Tahrir Square was re-named Liberation Square, which was previously overlooked by the British commissioner’s residence. In their place, new International Style buildings rose including the Mogamma Building hosting socialist government bureaucracy and the Arab League headquarters. These high-style modernist buildings were designed to project an image of a new Cairo and in turn a new and enlightened citizen.

-597b6453-8730-48c6-8077-79340e6d4734.jpg) Tahrir Square 1962

Tahrir Square 1962

The MerryLand Apartment

This modernism was also translated into residential architecture led by architect Sayed Karim in the MerryLand Apartment complex. In an attempt to address the needs of Cairo’s growing middle class, the complex leaned into modularity and efficiency, max-mixing living space as population rose. Like Yugoslavian residential blocks, apartments featured geometric balconies and were designed around shared outdoor spaces, cultivating a sense of community.

-58aa23c8-e41e-4c0f-9398-7106f8c3436d.jpg) Sayed Karim MerryLand Apartment Complex

Sayed Karim MerryLand Apartment Complex

The Zamalek Tower

Also designed by Sayed Karim, the Zamalek Tower responded to this growing population with vertical living solutions. The use of reinforced concrete allowed greater flexibility in floor planning, catering to both residential and commercial spaces in one area. Alongside individual balconies that provided shade and private refuge, rooftop terraces created additional shared outdoor spaces.

What united these disparate projects was an optimism bordering on audacity: the belief that new buildings could help produce a new citizen. Architecture was tasked with more than shelter or representation; it was meant to interrupt history, to open a window onto a different way of living together. In both Egypt and Yugoslavia, the modern city was imagined as an ethical instrument, capable of dissolving class divisions, managing differences, and cultivating collective life.

-27ca8b8c-ca84-4a7d-8099-9226e98a0b69.jpg) Zamalek Tower 1959

Zamalek Tower 1959

The Decay of Utopia

-2af6408b-b14a-4a0d-bd12-71337163c934.jpg)

Today, many of these buildings in both Cairo and Belgrade linger in a state of erosion, their outdated interiors and weathered façades depict cities suspended in time, where the promise of a once-radical utopia remains unresolved. Both Tito and Nasser sat at the helm of this social fantasy, yet with their deaths, the dream dissolved with them. In former Yugoslavia, following the war and dissolution of the nation-state, privatisation and governmental neglect hollowed out these once-idealistic structures. In Cairo, rapid urban change pushed mid-century modernism to the margins, caught between nostalgia and complete erasure.

Yet instead of focusing on the death of the Non Aligned Movement, these concrete utopias testify to architecture’s capacity to give material form to political imagination.

At a moment when architectural innovation is increasingly tied to luxury and spectacle, these projects recall a different ambition: building for the common good to call for class equality and de-colonialism. They remind us that cities can be more than buildings and that the pursuit of utopia can be a worthy cause.

Long after the photographs have yellowed and the leaders have passed into history, the dream they set in motion remains embedded in walls, courtyards, and streets – still asking what it might mean to design society from the ground up.