This Academy is Reviving an Ancient Cavalry Sport in Egypt

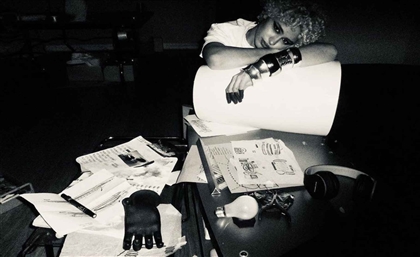

Aya Eissa is a world-class rider and coach who forged a path for tent pegging in Egypt by opening the country's first academy dedicated to the sport, proving that cavalry isn't just for men.

The first world Aya Eissa ever entered was a cartoon made real. She was four years old, astride a creature of immense and gentle power, and the mundane world fell mute. “It was as if you went inside the real Disneyland,” she says, her voice still carrying the wonder of that child. “And now connected to an animal that is a lot bigger than you… I was living in the cartoon world that all kids my age dream of entering.” For a long time, she lived in that vibrant, muted space, learning its language, its ins and outs, while the real one hummed indistinctly in the background. That world, it turns out, was the only real one. And the language she learned was that of the horse and the blade. Eissa is the founder of Egypt’s first civilian tent-pegging academy, Gallop Away. Tent pegging is a cavalry sport of ancient origin, where riders gallop at a flat-out run, leaning from their saddles to spear small ground targets with a lance or slash them with a sword. It is a discipline of pinpoint precision and visceral thrill, a relic of martial history preserved in the modern age. It is also, traditionally, a man’s world. Eissa, an award-winning international coach, referee and former champion, has spent her time immersed in that world, growing with a passion to reshape it in her own image. Her story begins with a singular obsession of a girl out of place. While her school friends discussed other children and people, Eissa held court on the intricacies of horses. “I would talk about something completely different—food, carrots, potatoes, and how difficult this horse was,” she recalls with a laugh. Her social life was the stable; her study hall, the saddle. “I would put a book on my horse’s neck during warmups to write my homework, to revise something quickly for a class.” This was her apprenticeship: a solitary, all-consuming dedication to a partner that could not speak, but communicated in more profound ways. The attraction to tent pegging was, for her, a natural pull toward the unique. “The crowded road does not attract me,” Eissa says. “I like things which are very unique, that when people look at it, they question it.” Growing up riding in a military club, she saw the performances—the thunder of hooves, the glint of steel—and a dream took root. “Maybe when we were young we didn’t see that as women we could do that, so this was, for me, a big dream. I loved the challenge.” The challenge, however, was institutionalised. For years, Eissa represented the military club, accumulating titles and international certifications, all while feeling invisible. People were surprised that a woman did this work. They wanted to see videos. “I got tired of the idea that the military clubs were the only ones playing tent-pegging,” she says. The courage to start Gallop Away was a slow-building pressure to use her voice, to make the sport inclusive, accessible. “I could do an interview like this, I could never do this before.” Leaving meant starting from nothing. Literally. Eissa's new domain was a patch of desert. “I had to fix the flooring, and organise this space with stables and buy horses," she recalls. "I was fighting time, people, the thoughts in my own head.” She built it with her own hands—the stables, the toilets, the training ground. She planted a tree and watered it daily, a living monument to her own metamorphosis. “I never thought I would do this with my own hand when I never washed a glass in my home.” While waiting for builders, she trained students in the desert next to the pyramids, exploiting space and time, a general marshalling her forces in the sand. The essence of her sport, Eissa explains, is a terrifying alchemy of discipline and danger. “We never play with fake weaponry, everything is real. You have to be a good rider with good intuition to act quickly but, more importantly, to not harm anyone or the horse.” It is a practice in intense presence. And it is one that routinely shocks the uninitiated. “Some people think we never play with real weapons and then they get extremely shocked. 'Oh my god, is that a real sword?’” Eissa's leadership in this hyper-masculine field was, initially, protected by her youth and her status as an officer’s daughter within the military club. She was blissfully unaware of the chairs she was pulling out from under men. “I didn’t understand that masculinity was suffocating.” The real world provided a swift education. “I would get parents like, ‘I cannot have a woman yell at my son during practice.’ Okay, then take him and leave. I will not get a man to train him.” Her response as a woman of sport was always in her performance, on the field. “I never felt degraded because I really carved my name on the stones of this game… I love to respond on the fields. Let’s see who will win.” The defining moment of that response came after a catastrophic injury in South Africa that shattered her right hand and derailed her architectural studies and her playing career. In her despair, a trusted voice delivered a crushing blow: “You were a champion at the time of the blind. The blind now can see, and you will have no place.” It was a sentence meant to crush her, and even though it did, it also provided the fuel for everything that came after. “The hit that really hurts pushes you super high.” Through a year and a half of surgeries and a lasting disability, Eissa learned to hold a weapon again before she could properly write. Her comeback victory was a silent, powerful rebuke. “I kneeled to God and said, thank you. I looked at that person and said, here I am, in front of everyone with eyes open.” This resilience defines her coaching. Eissa speaks of her students, boys and girls, as “projects.” “I do not accept failure.” Her academy’s success is in the dawning respect in parents' eyes. “I was looking forward to the look on their face at the end, not the beginning.” At the heart of it all is not ambition, but a profound, almost spiritual partnership with the horse. For Eissa, this is the central, unwavering truth. “It’s not a relationship… it is my good half,” she says, her voice softening. “I can have a lot of really bad things within me, but if you look at me and see my horse you’d see all that's good in me.” The horse, she explains, is an honest mirror. It teaches “the right and truth, the patience… you cannot lie to a horse. He sees you as the most beautiful.” When asked what she has learned from humans in comparison, her answer is swift and unadorned. “Don’t ask me about humans because I don't love them. I love horses so much more.” It is this pure, uncompromising love that drives her. She sees her work as an “ongoing charity,” an attempt to be an ambassador for the cavalry itself. She dreams of a place where the horse is recognised as a partner for healing and strength, essential “for every man, woman and child, sick or not.” For the young girls who now come to Gallop Away, her message is simple and powerful. “You’ll be something unique. How many girls in the whole of Egypt are doing the same thing? Twenty? From how many millions? We are super, super heroes.” She tells them to be patient, to understand that no one is born a champion. “The more you wait, the better places you get to.” Looking back, the only thing she would tell her younger, solitary self is to push even harder. “I wish I pushed myself more… I always say there is more, there is better.” It is the ethos of a rider who has learned that the highest point is not the destination, but a vantage point from which to see the next, unseen arena. The true skill is in the power required to stay, to hold your ground, and to make that ground your own.

- Previous Article Atop Downtown Cairo’s Mazeej, Greek Fusion Takes Reign

- Next Article Cairo University to Host Its First AI Conference on October 18th