This Saudi Palace Hosts Some of the World’s Oldest Islamic Manuscripts

A trip to the lavish Al-Meger Palace shows us how personal history and global architectural traditions magically coalesce.

The light in Saudi Arabia’s Asir province is different. It’s a high altitude light, thin and unforgiving, one that exposes every contour of the landscape—the stark granite outcrops, the improbable green of the juniper forests clinging to the slopes. And it is in this light, at 2,400 meters above sea level, on what was once barren land—a place only the hardiest wildlife dared to inhabit—that Mohammed Al-Meger built his palace. Not a palace in the conventional sense of inherited power or dynastic ambition, but a palace born of something far more personal, a repository of memory. A place that could only exist precisely where it does, a singular point on the map, a convergence of disparate histories.

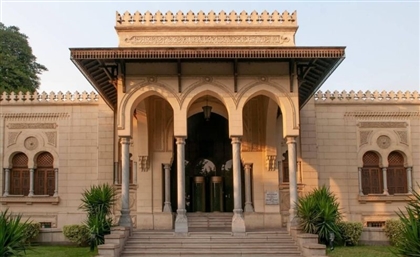

Thirty-five years. Eighty million Saudi Riyals. These are the quantifiable metrics of Al-Meger Palace. But they tell only a fraction of the story. The numbers—like the two million stones sourced from the Asir region, the 360-plus windows tracing the sun’s relentless arc, the 365 columns within—are merely the frame. The true subject, the heart of this improbable edifice, is the story of a man, orphaned young, expelled from school, who found solace not in textbooks but in the world itself.

Al-Meger’s journey reads like a picaresque novel—from tending village animals, his sustenance the milk they provided, to schooling in Nablus and Jerusalem’s Terra Sancta College. A failed attempt at medicine, a stint in the military, a sojourn in the United States. He drifted—Europe, Spain, Andalusia, the Philippines, Indonesia. A restless search for a place to belong before finally returning to Al-Namas, the place he had left behind. But he returned transformed, his mind a palimpsest of the places he had seen and the histories he had absorbed.

The palace is a distillation of these experiences. It’s a physical manifestation of Al-Meger’s own personal odyssey. The architectural details—a confluence of world cultures, with a pronounced emphasis on Islamic design—can confidently speak to this. Umayyad and Abbasid influences mingle with Andalusian flourishes, creating a visual design as intricate as the thousands of Islamic motifs adorning the interiors. Seven domes crown the structure, each symbolizing a continent, a gesture towards global unity—a grand, almost utopian vision etched in stone.

But within this grand design lies a deeply personal narrative. The palace’s genesis can be traced to the discovery of a supplication manuscript penned by Al-Meger’s father—a tangible link to his past, and, later, a catalyst for his future. The palace became a way to immortalize his family’s legacy, to give physical form to the intangible threads of memory and lineage. His time in Jerusalem, observing the layered architectures of that ancient city, had sparked his interest. Travels to Spain and Andalusia further fueled his fascination with Islamic civilization, leaving an indelible mark on his aesthetic sensibilities.

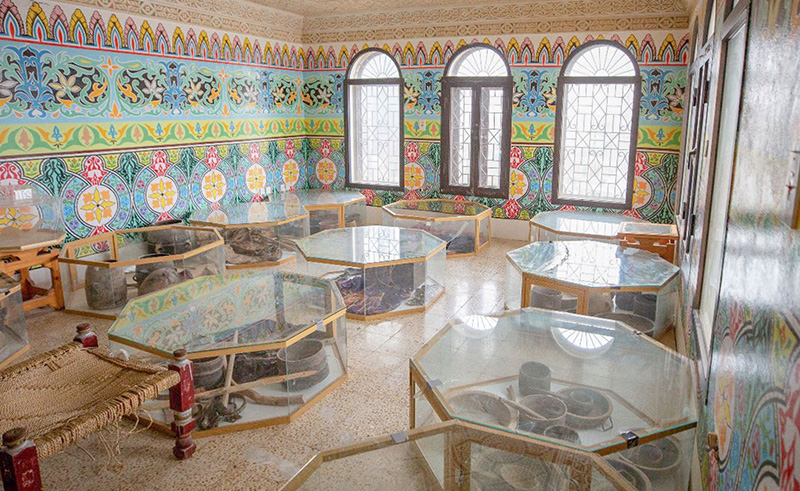

The museum within the palace holds treasures of its own—some of the oldest manuscripts from Islamic history. Sixty volumes from the time of the Prophet Muhammad, thousands of handwritten Qur’ans. Ancient texts on medicine, mathematics, astronomy—artifacts rescued from across the country, particularly the south. One manuscript, penned by Jamal Al-Din Ibn Tumert Al-Andalusi in 720 AD, hints at early Arab advancements in chemistry and physics. Scholars, historians and voyagers have been drawn to the palace, marveling not only at its architectural ingenuity—the astronomical design, the light tracing its daily path—but also at the sheer rarity of these manuscripts.

Al-Meger hired twenty builders from India, Pakistan, and the Philippines—a small international cohort—to realize his vision. It’s a telling detail, this gathering of disparate talents in a remote corner of Saudi Arabia. It speaks to the universal language of craftsmanship, and the shared human impulse to create something enduring.

The Al-Meger Palace is more than a museum, more than a monument to one man’s life. It’s a beacon of local architectural heritage, a reminder of historical significance and resilience—a testament to what can be built, both literally and figuratively, from the fragments of a challenging past. It’s a place where the light, that unforgiving Asir light, illuminates not just stone and manuscript, but the enduring power of human endeavor. It stands there, immutable, a singular point in the world, a convergence of personal history and global heritage.