Inside Inji Aflatoun’s Prison Cell

Jailing her did little to bend her will; instead, it gave the world an insider’s view into the State’s gated complexes.

Originally Published on September 30th, 2024

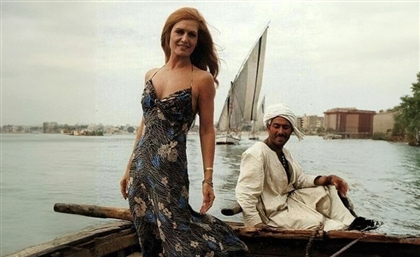

This is Inji Aflatoun in 1963, writing to her sister Gulpérie in French from her prison cell just months before her release:

“I still paint a lot, with determination and inspiration; the subjects are always the same but with a new vision, a purer and more sober vision; for me, it’s about constantly renewing myself in this world of the unrenewable and the complete banality in which we find ourselves.”

As forbidding as it must have been, a four-year sentence did little to quell Aflatoun or her political and artistic resolution. Instead, it became a period of time she looked back upon with ambivalent feelings - relief, for no longer having to endure its deprivations, and longing, for it produced not only her most defining bodies of work, but also case-hardened her like no other formative experience.

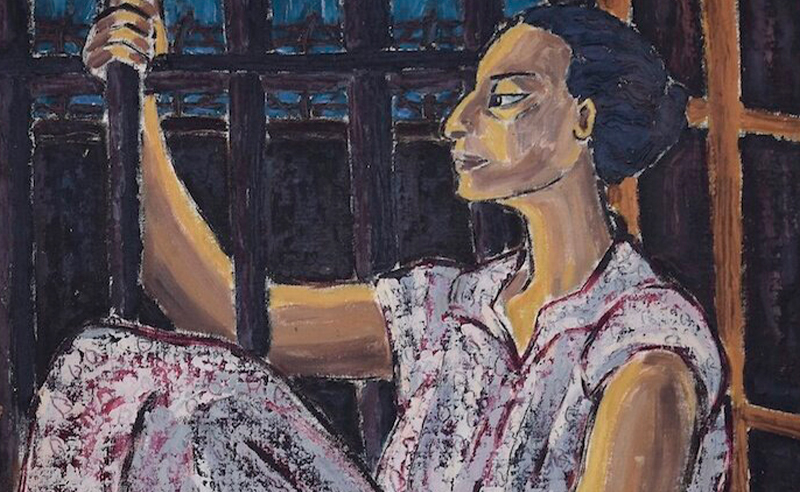

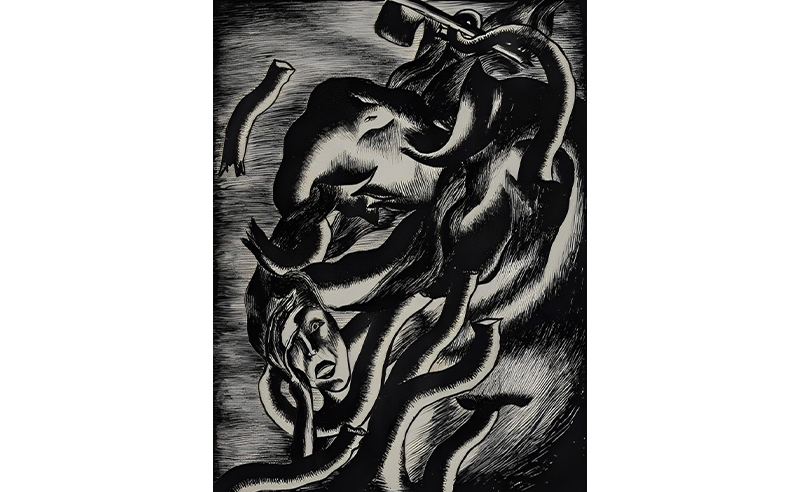

Dreams of the Detainee, 1961

Dreams of the Detainee, 1961

Her crime was her allegiance to Communism. She was sentenced, in 1959, as part of a cohort of other women following an unprecedented number of female political arrests, an event she would later describe in her typical caustic bent as “the first time the government felt that women were as important and effective as men.” Aflatoun was taken to Al-Qanater prison, 15 miles north of Cairo. Those who knew her or—considering her rising national fame - knew of her, grieved the loss of her voice. Others, including her father, believed it was only a matter of time. Since birth, according to both her parents, she had been a rebellious force, but she also had an artistic flair that nothing seemed to extinguish.

She was born Inji El-Kashif (‘Aflatoun’ being an inherited family sobriquet) in Cairo in 1924 into a noble family of immense means on the cusp of her parents’ divorce. She spoke only French, and didn’t learn Arabic until she was 18. She was sent to the Sacré Cœur, but at 14 had to be transferred out due to her constant defiance of the rigid Cardinal system. To demonstrate the brutality of the school to her parents, she sketched it on paper. In her drawings, the nuns were scrawny, ghost-like figures looming over her slight and listless self. It was among the first telltale signs indicating that she was in possession of a talent far greater than either parent knew what to do with.

In the more liberal Lycée, she was able to find a place for herself after instantly falling in with a like-minded crowd. There she encountered, for the first time in a long life of political associations, the basic tenets of Marxism. At home, she felt a growing rift between her family and her beliefs, and she was precocious enough to know, even at that age, that the two were fundamentally at odds. Again, she turned to art to channel her disquiet. At 18, she began and completed The Monster (‘El-Wahsh’), one of many oil-canvas paintings forming her life’s œuvre. It’s a deeply unsettling painting of a surreal hellscape dominated by jagged, shadowy hills and trees. There are clear parallels with Dalí’s Persistence of Memory, almost as if Aflatoun had taken his same landscape, incinerated it, and painted the aftermath.

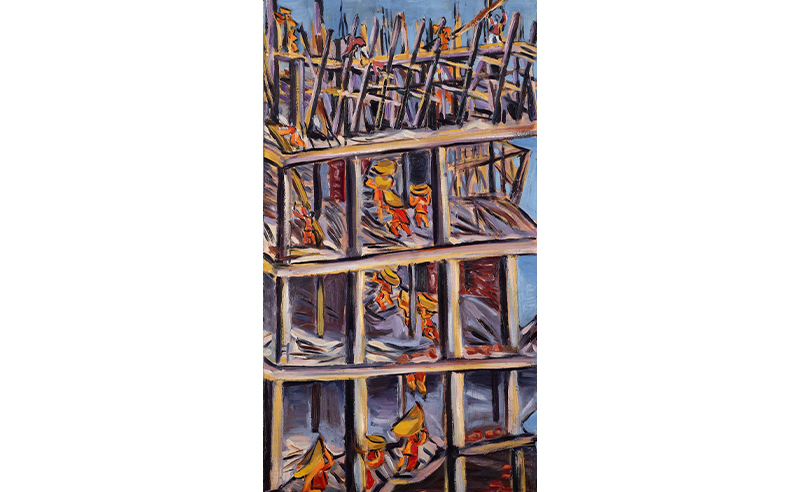

The Worker, 1950

The Worker, 1950

No one was more impressed by - if not, on account of her opulent background, equally sceptical of - her work than Kamal El-Telmessani, a major exponent of Egyptian surrealism who, eight years later, would go on to co-found the Art et Liberté movement. When she first met him, he had come in the guise of her personal art tutor, commissioned by her mother to nurture the young Inji’s talents. In El-Telmissany, she found a mentor not only in the arts but also in her political drive. In 1942, at age 18, she joined Iskra, a Communist youth party.

It was a time when the British occupation had remained largely unchallenged, and one particular event was ingrained deep within Aflatoun’s psyche: the Denshawai Massacre of 1906. Using ink on paper, she depicted an Egyptian farmer hanging limply from a noose, before him the destruction of his village at the hands of British troops. A woman is weeping in the background, and beneath the farmer’s bare feet, English soldiers are proudly hoisting up their bayonets like the Union Jack.

There were many other decisive events that transformed Aflatoun from an inquisitive scion of the aristocracy to one of its most radical opposers. The 1946 Abbas Bridge incident, which saw the death of several student protesters, was another such incident. As soon as she had fledged, Aflatoun became unstoppable, participating in - sometimes even leading - major protests calling for workers and women’s rights. Wherever she went, on the streets of the city or in the rural homes of farmers (whom she regarded as the synecdoche of the everyday Egyptian), she received an oral education that further stoked her invincible convictions.

The Monster (El-Wahsh), 1942

The Monster (El-Wahsh), 1942

Her wealth allowed her to travel to Paris in November 1945, where, assuming the Egyptian delegation, she spoke at a women’s conference alongside such speakers as survivors of the Holocaust and escapees of Fascism:

“The Egyptian woman refuses to remain as she is now, deprived of all her rights. She refuses to be the worker who receives a third of the man's salary for the same work and without any social insurance. She refuses to be the employee who is prevented from holding high positions due to tradition.”

During the years that followed, Aflatoun oscillated between art and politics, but it was clearly the latter that most consumed her. In the late 1940s, she nearly abandoned her work altogether in pursuit of activism, setting off the ticking time bomb that would later result in her incarceration. She married in 1948, and, at the request of her husband Hamdi, returned briefly to the easel. By then, the sway of surrealism was nearing its end in the world, and all the influences from Aflatoun’s Art et Liberté education were beginning to fade. In its place, a fresh, new style of Expressionism mixed with Social Realism began to blossom on her canvases. Works like The Worker (‘Hamel Al-Toub’) and Construction Workers (‘’Omal Al-Benaa’’), both completed in a 1950 collection, showcase workers in their rugged work environments. Here, her subjects are toiling away on top of scaffolds or labouring to carry bricks on their aching backs, and always present in these paintings is a sense of gross injustice suffered by society’s most exploited labourers. That Aflatoun chose Expressionism was no coïncidence; she used it to hyperbolise that suffering beyond what Realism ever would have allowed, as though she’s pleading for help saying: “Look what is being done to your fellow man!”

Construction Workers (Omal Al-Benaa), 1950

Two years later, the same year she held her first art exhibition, the Free Officers swept to power, effectively dismantling the British occupation, yet the political grievances of yesteryear were all but forgotten, especially by Aflatoun, who only became more tetchy by the day. When she wasn’t leading protests on the streets, she was documenting them with her art. The death of her beloved husband in 1957 was the closest she came to breaking, but even then she was able to power through.

After Egypt and Syria briefly united in 1958, the Nasser administration, increasingly wary of external threats, began a large-scale crackdown campaign on Communist leaders in the country. Aflatoun’s house, occupied at the time by her mother while she was abroad, was subsequently raided by the State. Against everyone’s pleas, she returned home, exhibited her latest work, and kept a low profile. Her efforts proved futile when in June 1959, she was seized from her hideout on the outskirts of Shubra.

........

Qanater prison was a 12-ward facility in Qalyubia with a notorious record. Before she arrived there, Inji Aflatoun’s name had already been on everyone’s lips. Inmates, as well as the warden, the maids, and general staff members, knew they were in the presence of a special kind of convict. Some of them had known her through her art, others, whose fates were sealed in the same political chokehold as hers, had marched alongside her on the streets of Cairo. Her grandeur notwithstanding, she insisted on an equal footing with her inmates, refusing any kind of exceptional treatment. Thus the artist, once in the vanguard of her craft, was stripped of her tools, but never, as it turns out, of her vigour.

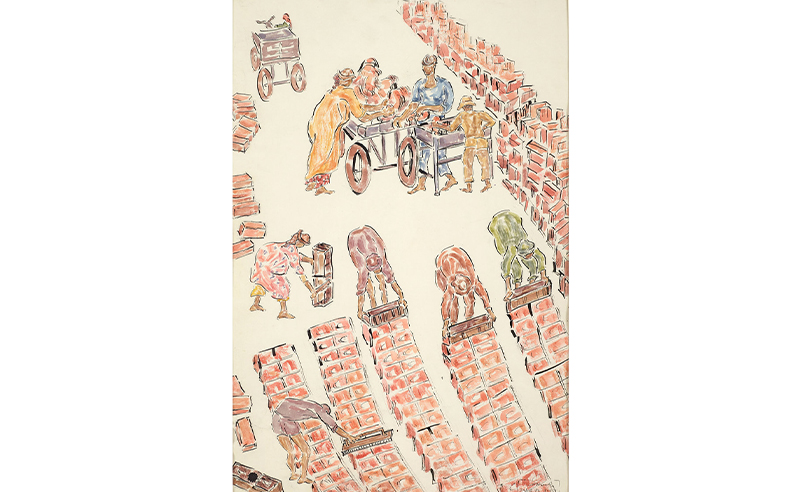

Brick Workers, 1980

Brick Workers, 1980

She was once more in a position to learn about a faction of society whose existence her original milieu had long antagonised, if not altogether ignored. She heard story after story from women whose lives had been torn asunder when the state spirited them away from their families. Most of all she observed, in the dead silence of her cell, as the other women pressed their faces up against metal bars in abject desperation, or when they lay prostrate on the solid floor, trapped in the void of their apprehension. In those moments, she longed for the brush and canvas, not out of ennui, but sheer necessity. She needed to do what she’d always done: document reality through her eyes. But how?

As luck would have it, the prison warden, a stout and quick-tempered man known as Major Hassan El-Kurdi, happened to be something of an aesthete himself. One morning, on a visit to the facility during an inspection check, he was shocked to learn that Inji Aflatoun, now an inmate serving time on his premises, was without her art supplies. It was an opportunity of a lifetime, the warden believed, to have someone of such renown as she painted his institution. He took the initiative to bring in everything she needed - brushes, oil colours, canvases, even an easel - on the condition that whatever she painted, the prison would either keep for itself or sell on its own account. Between the conditions proposed and the thought of idling for another four years, she agreed to the terms.

El-Kurdi’s decision inadvertently ushered in Aflatoun’s most influential and closely-studied period of all: the Prison Collection.

Arbres (Al-Achgar), 1960

Arbres (Al-Achgar), 1960

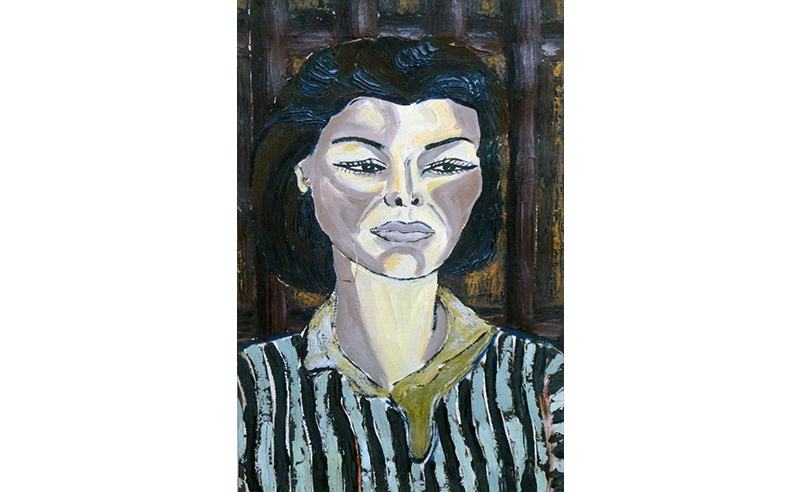

She started by painting fellow inmates in simple yet expressive portraits. In one piece titled Portrait of a Prisoner, the subject is a downcast, dark-haired woman donning traditional prison stripes. The brushwork is bold and deliberate, with thick lines and pronounced facial features. There is a palpable tension between strength and suffering in her expression, accentuated by a claustrophobic background of metal bars. But perhaps the most important detail Aflatoun manages to capture is the profound emptiness in the woman’s eyes, the same emptiness that quietly filled her, too.

Over time, her focus shifted away from the single subject and onto larger, more communal settings, as seen in Femmes accroupies. Here, a group of women are seen squatting next to a door leading to the outside courtyard. They are patiently waiting for it to open so they can go for their daily walk. Amazingly, she found herself again drawing exploited individuals toiling away over menial, collaborative labour.

Portrait of a Prisoner, 1962

Portrait of a Prisoner, 1962

As her canvases left her cell and entered the warden’s office, she quietly stashed the ones dearest to her, away from the prison’s rapacious grip. Unbeknownst to El-Kurdi, Aflatoun was smuggling some of her work out of the facility by way of handing them to complicit nurses and turnkeys. Those women would then tuck the rolled-up paintings underneath their garments and carry them out to safety.

The years passed, and she was still confined to her cell. When she exhausted all possible subjects, she looked elsewhere. Her concentration was beginning to atrophy. The fear of losing all recollection of her past slowly started seeping in. Looking out her window through the wrought-iron bars, she could see a flame tree in the near distance. For the first time in her life, she felt impelled to draw not the people around her, but the nature that prison had so forcefully deprived her of.

Perhaps the most potent depiction of her prison period is her painting of the flame tree, which she reproduced over and over in various interpretations. With each version, she envisioned a moment in the future where she would once again be united with the outside world. In later interviews, Aflatoun would go on to credit her jail time with her newfound appreciation of nature.

With a little help from her family, she reached an agreement with the warden that allowed her to go up on the roof each day, for two hours before sunset, in order to paint her landscapes. There, she produced paintings of sailboats on the Nile before the backdrop of Al-Qanater’s lush gardens.

Finally, in 1962, a breakthrough came.

It was the year of Yemen’s Civil War, an affair in which Nasser and his administration had gotten dangerously entangled. Pressure mounted in the country as Egyptian troops were being shipped out to foreign battlefields. It was also at that time when Egypt recorded its first ever female prison strike, led by none other than Inji Aflatoun herself. For 17 days, the unrest grew beyond containment, with prisoners refusing to eat. Their motto was terse and concise: “Release or Death.” Soon after, more pressure came from abroad. A campaign by The International Women’s Federation and Amnesty International called for their freedom.

Memory Sews Together Events That Hadn't Previously Met, 1974

Memory Sews Together Events That Hadn't Previously Met, 1974

On July 26th, 1963, Inji Aflatoun, along with a group of other prisoners, was released. For the rest of her life, she would never again put down her brush. To reflect her ascent from prison’s grim and tenebrous aura, she transitioned from dark and leaden tones to rich and brilliant colours of every shade. There was life blooming on her canvases again. Despite the time she spent in jail, or perhaps because of it, the strive for social equality was still at the forefront of her work. She painted workers again and again, giving them a voice and elevating their struggles to reach national debates.

On April 17th, 1989, Inji Aflatoun died in Cairo. She was mourned by millions both at home and abroad. A hundred years after she was born, as the world showcases her work in one global exhibition after another, the reminder is clear: the monolithic Egyptian artist is anything but forgotten…

- Previous Article Italian-Palestinian Duo No Input Debuts Eponymous Electro EP

- Next Article Egypt & UNIDO Partner to Boost Sustainable Cotton Production

Trending This Week

-

Dec 22, 2024

-

Dec 26, 2024