Painting a Pain-Splattered Portrait of Palestinian Poet Mosab Abu Toha

While his family campaigned for his release across social media platforms, I found myself striving to craft a paint-splattered portrait of Abu Toha through his body of work.

“A book that doesn’t mention my language or my country, and has maps of every place except for my birthplace, as if I were an illegitimate child on Mother Earth.”

Excerpt, titled ‘A’, from Mosab Abu Toha’s Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear.

In the poetic tapestry of his words, award-winning poet, scholar, and librarian, Mosab Abu Toha, conjures Palestine, a literary space where the voices of the voiceless resonate. Each verse mirrors a lineage fractured by the harsh clasp of a brutal occupation, narrating the untold tales of a dispossessed people. Within his verses lies a Palestine relegated to the recesses of memory, a landscape cherished only by those privileged enough to have embraced its beauty. Houses that once cradled love for a homeland now stand as relics fading into the past.

Resisting the Israeli mission to bury his people's narratives beneath the rubble, he confronted their efforts. Yet, in a violent act of suppression, Israeli forces detained Abu Toha as he sought to evacuate Gaza on November 20th, 2023.

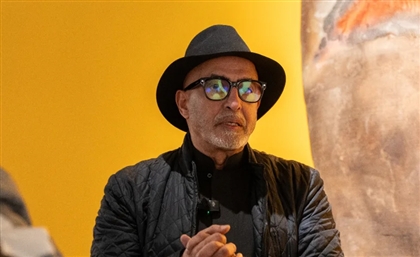

Image credit: Wissam Nassar

Image credit: Wissam Nassar

In the fleeting moments preceding the Israeli escalations, Abu Toha, in a poignant piece penned for the New Yorker titled ‘The View From My Window in Gaza’, unveiled a raw account of unfolding events. His narrative unfurled with an acute awareness of the present: family in a hurried exodus from their homes, an uncle strategizing refuge in Jabalia camp, and him, contemplating a journey by bike to the presumed safety of Southern Gaza.

As the piece progressed, Abu Toha's perspective on Gaza grew cloudy, drawing the reader into a tumultuous dance. Struggling to preserve the image of the bakery before its role as a lifeline for a hungry populace, and the streets void of the vociferous pleas for aid, readers sway in a response echoed by the conflicting impressions depicted.

Yet, whilst readers only received heart-wrenching intimations, Abu Toha’s reality dimmed by the second. The more he biked, the more the smell of burned flesh settled into his lungs. The deeper he delved into Gaza's remnants, the further disillusionment etched its mark on his thoughts.

Abu Toha's writing bore the weight of urgency, a tragic burden held by his inky fingers. His New Yorker piece intensified his critical stance. Yet, only he knows the sting of documenting, relegated solely to the role of eulogist.

In a poem titled ‘What is Home?’ Abu Toha writes:

“What is home:

it is the shade of trees on my way to school before they were uprooted.

It is my grandparents’ black-and-white wedding photo before the walls crumbled.

It is my uncle’s prayer rug, where dozens of ants slept on wintry nights, before it was looted and put in a museum.

It is the oven my mother used to bake bread and roast chicken before a bomb reduced our house to ashes.

It is the café where I watched football matches and played—

My child stops me: Can a four-letter word hold all of these?”

Abu Toha’s words bear dire consequences and yet the innocent constructs of their ask add insult to injury. In reading, one ponders when 'resistance' fused with the rawness of pain, when 'fighting back' lost its boundaries. When his ‘opposing’ words are merely putting diction in place of family portraits being blasted into shrapnel, how far gone must one be to assume them ‘threatening’?

In another poem titled ‘Palestinian Streets’, Abu Toha depicts the trauma-born world history books would never bind:

“My city’s streets are nameless.

If a Palestinian gets killed by a sniper or a drone,

we name the street after them.

Children learn their numbers best

when they can count how many homes or schools

were destroyed, how many mothers and fathers

were wounded or thrown into jail.

Grownups in Palestine only use their IDs

so as not to forget

who they are.”

Abu Toha's words hold no excess; they unveil what eyes overlook. He gives shape to realities escaping archives, expressing the ache of a geography not meant for mapping but for dismantling. Blood does not mar his language, for those with guns taught him words his schools could never endure.

Image credit: Said Khatib

Image credit: Said Khatib

Arguably one of his most heart-wrenching works, 'Sobbing Without Sound' comprises an emotive sequence of irreproachable desires:

“I wish I could wake up and find the electricity on all day long.

I wish I could hear the birds sing again, no shooting and no buzzing drones.

I wish my desk would call me to hold my pen and write again,

or at least plow through a novel, revisit a poem, or read a play.

All around me are nothing

but silent walls

and people sobbing

without sound.”

Saturated with yearning, 'Sobbing Without Sound' carries, within its lucid expressions, the weight of an indescribable anguish. Abu Toha aches for the commonplace, a concept that faded as normalcy shed its peaceful skin. In each line, he engages in a rememorying, summoning an intangible past while moulding a poignant, yet tragically fictionalised, tangible present.

Abu Toha’s kidnap is not an isolated event. Since October 7th, Israel has detained 4,000 labourers and over 1,000 individuals in the occupied West Bank. His release was officially declared on November 21st, following relentless appeals from the literary community and his broader readership, demanding an end to his unjust abduction.

The extensive distribution of Abu Toha’s work following his abduction on November 20th exposes the harsh reality of how art is consumed and revived amidst tragedy. It took days of publicised injustice for me to pause and truly understand. It took a sinister effort to stifle voices for me to acknowledge what had always been present. While his family campaigned for his release across social media platforms, I found myself striving to craft my own paint-splattered portrait of Abu Toha through his body of work.

- Previous Article Italian-Palestinian Duo No Input Debuts Eponymous Electro EP

- Next Article Egyptian Embassies Around the World