Tattoo Designer Yehia Moldan Translates Arabic Into Geometry on Skin

Yehia Moldan transforms Arabic letters into abstract geometric tattoos, creating a language that maps his journey from Gaza to Sweden, and Berlin to Cairo.

Palestinian-Swedish tattoo designer Yehia Moldan created a language that only he knows, a tattoo language that transforms Arabic letters, words, and phrases into abstract geometric works of art. His style is immediately recognisable, established through thousands of designs created over the past seven years. Some are tatted on celebrities like Palestinian musician Saint Levant, Lebanese actress Taraf Al Taqi, and Egyptian actor Mohamed Hatem—just a few of the people who have taken Moldan’s work off of his Instagram page and etched it into their skin.

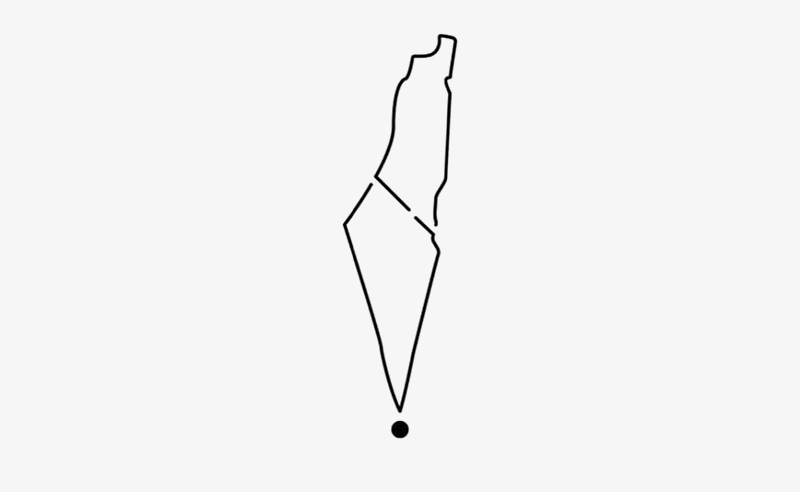

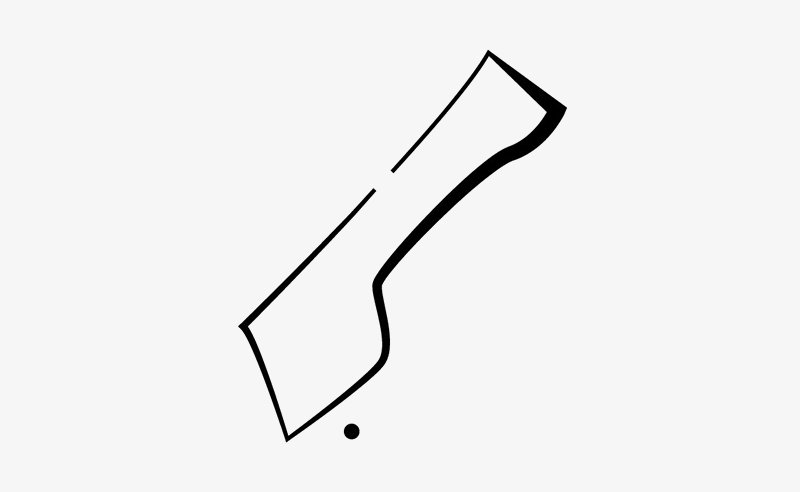

Moldan designs each letter based on its Arabic form: a meem (م) may appear as an open shape like a diamond or circle, while an alif (أ) crosses or stretches as a single line. Sometimes, Moldan draws shapes we know with obvious connections to their source—like حب, or ‘love’, in the shape of Palestine. But his classic is a linear series of clean lines, dots, triangles, and circles that takes inspiration from the traditional Viking, Amazigh and Bedouin tattoos.

Moldan blew up on social media in 2019 for designs that called for revolution, resistance, and justice. But he leaned into politics more out of necessity than desire.

“I didn’t want to be a political artist, but things got heavy everywhere—Lebanon, Sudan, Yemen, Syria, Palestine,” he said, “so I couldn’t get away from it.”

Born and raised in Gaza, Moldan has never denied his Palestinian identity, but for years, he was trying to run away from its politicisation. “My Palestinian identity is not my only identity,” he emphasised. “I’d rather it be a footnote at the end, not the headline.”

When he went viral, Moldan was living in Berlin and embracing the lifestyle. He was partying for days, and his designs reflected it. “Berlin was vulgar,” he said.

Moldan himself has 13 tattoos, most of which were done impulsively, decisions born in the heat of the night.

“This one is my favourite.” He lifted his left arm and pointed to a smiley face, sitting next to a single dot of ink and an empty conversation bubble. He laughed. “It was drawn by my friend who never draws, and tattooed by another friend who had never held a tattoo machine.”

If you asked Moldan what his slogan is, he would say: “Tattoos are there to regret.” But as of late, he’s thinking of changing it to: “I do lines.”

A tattoo, he says, is a permanent reminder that you will continue to evolve. It is meant to commemorate a night, a period of your life, or a version of yourself, that naturally, you will never live or be again.

A conversation about ink turned into one about language—spoken, written, and tattooed. Its limits, depths, and transformative force. About the versions of ourselves we find in the different languages we speak, and how we evolve through them all.

Moldan has lived in Gaza, Egypt, Sweden, Tunisia, and Berlin. He knows four languages, if you count the one he created himself. A different version of Moldan lives in each place and language—his tattoo designs chart a map of that journey.

Moldan associates Arabic, his mother tongue, with Gaza, where he lived for the first 22 years of his life. Moldan learned English in Egypt when he left Gaza in 2011, a transition period while he was applying for political asylum in Sweden. Today, he would say the ‘romantic’ and ‘reasonable’ Moldan exists in English, but back then, it was the ‘vulnerable’ and ‘fragile’ Moldan.

English was an unfamiliar tongue, in a somewhat familiar country that he had visited as a child. But Malmö, Sweden, was neither familiar in language nor culture nor weather. Moldan arrived in 2013 and stayed for the next six years where he became a Swedish national. In the sunless, Nordic country, the word that dominated his thoughts was ‘alien’. Feeling out of place gave birth to a similarly fractured language. Moldan spent much of his time alone in his room developing the geometric Arabic alphabet and getting lost in an infinite world of design.

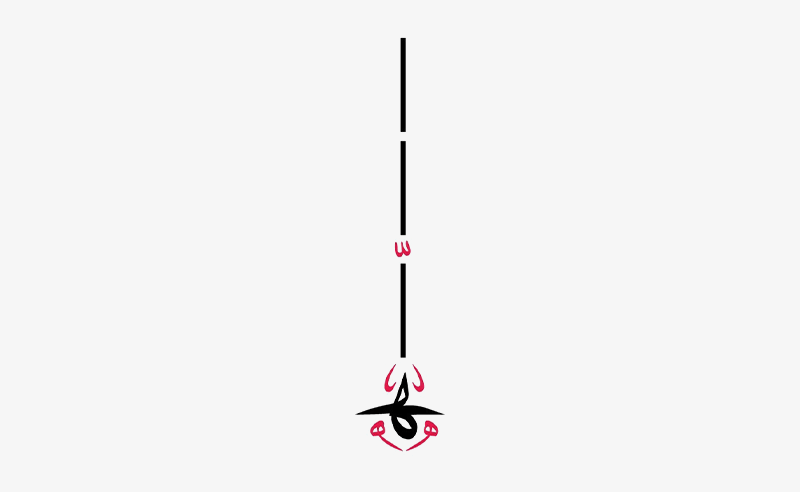

One of the only tattoos he has designed for himself emerged from a moment of spirituality during his time in Sweden.

“It says ‘Allah’,” he said, lifting the same forearm to expose the design. “But most people think it looks like Wi-Fi bars.”

Moldan explained that he was inspired by Libyan writer, Ibrahim Al-Koni, who wrote that when ancient Egyptians attempted to define ultimate power beyond the universe, the force could not fully be captured in language. So they came up with just a sound—‘la’. From there, the word ‘Allah’ was born. Moldan captured this sound phonetically with the Arabic letter ‘ل’, lam, conceptualising it as semicircles layered atop each other—what, yes, may look to some like Wi-Fi bars.

“My designs say ‘fuck the way you think about writing’,” he said about his geometric interpretation of Arabic. That defiance, he says, is born from a deeper tension within the language.

“There’s a certain holiness around Arabic letters and the Arabic language itself, a sacred weight carried through history,” he explained. “My work aims to break that holiness, not out of disrespect, but as part of a journey to free Arabic letters from the cultural and religious frameworks they’ve been trapped in.”

After Sweden, Moldan spent a year in Tunisia, then made his way to Berlin. The city defined by its nightlife and creative scene is where Moldan became an extrovert. He was constantly meeting people and embracing his social side—which wasn’t entirely sustainable. In Berlin, he was less connected to the hobbies and art, but this was also where his career as a tattoo artist took off.

Now, for the past year in Cairo, Moldan has found a balance. Egypt is not Berlin, and it’s not Sweden. Here, Moldan returned to the place he first lived in exile, where he learned English for the first time—somewhere between the extrovert he was in Berlin and the introvert he was in Sweden.

“Egypt gives me both,” he said. “I can choose between the two, and it’s a privilege.”

Perhaps Cairo is where all his languages meet, where he draws from each vocabulary to speak in a dialect that resonates uniquely with this chapter of his work, his life, and an ever-evolving Yehia.

- Previous Article Noor Alazzawi's Forecast for the Fall/Winter Transition

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Mar 11, 2026