Ten Egyptian Artefacts That Remain Outside the Country

With the news of the Netherlands returning a 3,500-year-old Egyptian sculpture this week, here is a list of ten important Egyptian artefacts that are still held abroad.

Earlier this week, Dutch Prime Minister Dick Schoof announced his government would be returning a sculpture from the reign of King Thutmose III to Egypt, where it had been illegally taken during the 2011 Revolution and sold abroad. The announcement was made in the wake of the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum and was met with praise and applause by many Egyptian observers.

In recent years, there have been increasing calls by Egyptians (and by many people of formerly colonized countries) to bring home their country’s lost artefacts. However, the story of how artefacts came to leave a country is often complicated. Oftentimes they were looted, but sometimes they were given as gifts (or otherwise lawfully taken). In any case, in an effort to commemorate the Grand Egyptian Museum becoming the largest museum in the world dedicated to one civilization, here is a list of some of the Egyptian artefacts you still won’t find there.

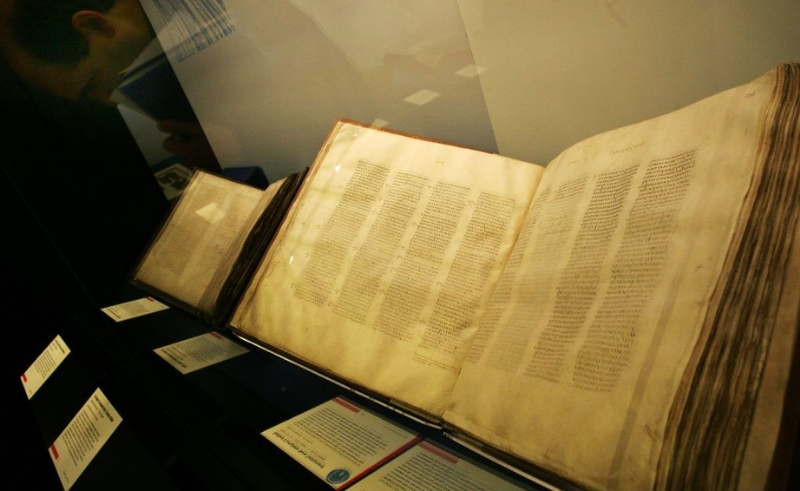

1) The Oldest Bible in the World (British Library, London) The Codex Sinaiticus, also known as the Sinai Bible, is the oldest complete copy of the New Testament ever found. Dating to around 350 CE during the time of Roman Egypt, it is also the youngest artefact on this list. (The timeline of the Grand Egyptian Museum, which chronicles ancient Egyptian history from prehistoric times to the Greco-Roman period, ends at 400 CE.)

The story of how this Bible left Egypt is complicated. Although the Bible was found in Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai in 1844 by a German theologian, it was given to Tsar Alexander II of Russia, and then sold to the British Museum in London in 1933 by the Soviet government. Today, most of the manuscript remains in British Library (where very few scholars have been allowed to see it in full), though smaller fragments are still scattered across Germany, Russia, and St. Catherine’s Monastery.

2) Luxor Obelisk (Paris)

The Codex Sinaiticus, also known as the Sinai Bible, is the oldest complete copy of the New Testament ever found. Dating to around 350 CE during the time of Roman Egypt, it is also the youngest artefact on this list. (The timeline of the Grand Egyptian Museum, which chronicles ancient Egyptian history from prehistoric times to the Greco-Roman period, ends at 400 CE.)

The story of how this Bible left Egypt is complicated. Although the Bible was found in Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai in 1844 by a German theologian, it was given to Tsar Alexander II of Russia, and then sold to the British Museum in London in 1933 by the Soviet government. Today, most of the manuscript remains in British Library (where very few scholars have been allowed to see it in full), though smaller fragments are still scattered across Germany, Russia, and St. Catherine’s Monastery.

2) Luxor Obelisk (Paris) If you’ve ever been to the Luxor Temple on the east bank of the Nile River, you will have noticed that in the entranceway there stands only one obelisk, the other clearly missing. Carved during the reign of Ramses II of Egypt’s New Kingdom, the missing granite obelisk now sits in the center of Place de la Concorde in Paris. It was gifted to the French Empire by Muhammad Ali Pasha in 1829 as a gesture of friendship, and it remains the oldest monument in all of France.

3) The Oldest Woven Dress in the World (Petrie Museum, London)

If you’ve ever been to the Luxor Temple on the east bank of the Nile River, you will have noticed that in the entranceway there stands only one obelisk, the other clearly missing. Carved during the reign of Ramses II of Egypt’s New Kingdom, the missing granite obelisk now sits in the center of Place de la Concorde in Paris. It was gifted to the French Empire by Muhammad Ali Pasha in 1829 as a gesture of friendship, and it remains the oldest monument in all of France.

3) The Oldest Woven Dress in the World (Petrie Museum, London) The Tarkhan dress, a linen garment that was once likely once worn by an Egyptian worker, is a 5000 year old piece of clothing—the oldest woven garment ever found. The dress was found south of Cairo in 1913 by Flinders Petrie, a British archaeologist, who at first believed it to be little more than a rag. He decided to take the rag with him to London anyway, and it wasn’t until the clothing was carbon-dated in 2015 that the true age—and significance—of the dress was understood.

The roughly size 2 dress remains in remarkably good condition (for its age), featuring a V-neck cut and long sleeves, and armpit stains left by its original wearer.

4) The Oldest Complete Map of the Ancient Sky (Louvre Museum, Paris)

The Tarkhan dress, a linen garment that was once likely once worn by an Egyptian worker, is a 5000 year old piece of clothing—the oldest woven garment ever found. The dress was found south of Cairo in 1913 by Flinders Petrie, a British archaeologist, who at first believed it to be little more than a rag. He decided to take the rag with him to London anyway, and it wasn’t until the clothing was carbon-dated in 2015 that the true age—and significance—of the dress was understood.

The roughly size 2 dress remains in remarkably good condition (for its age), featuring a V-neck cut and long sleeves, and armpit stains left by its original wearer.

4) The Oldest Complete Map of the Ancient Sky (Louvre Museum, Paris) The Dendera Zodiac is a celestial map from the time of Ptolemaic Egypt, depicting the twelve zodiac signs (a Greek invention) with Egyptian imagery and style. It was likely created during the reign of Cleopatra, around 50 BCE, and was etched into the walls of the Dendera Temple of Hathor north of Luxor. Besides its beauty, its significance lies in the fact that it is the oldest (and possibly only) known complete map of the ancient sky.

The French removed it from Egypt in 1821 (with some versions of the story claiming they used dynamite to do so), and today it can be found in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

5) The Rosetta Stone (British Museum, London)

The Dendera Zodiac is a celestial map from the time of Ptolemaic Egypt, depicting the twelve zodiac signs (a Greek invention) with Egyptian imagery and style. It was likely created during the reign of Cleopatra, around 50 BCE, and was etched into the walls of the Dendera Temple of Hathor north of Luxor. Besides its beauty, its significance lies in the fact that it is the oldest (and possibly only) known complete map of the ancient sky.

The French removed it from Egypt in 1821 (with some versions of the story claiming they used dynamite to do so), and today it can be found in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

5) The Rosetta Stone (British Museum, London) Many people believe that the Rosetta Stone was taken by the British from Egypt, but in reality, it was taken by the British from the French, who took it from Egypt. Discovered by French soldiers in the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in 1799, this stone is perhaps the most important archaeological discovery of all time (and it remains the most visited artefact in the British Museum). Its decryption paved the way to understanding ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics (and with it most of ancient Egyptian history), which until then had been illegible to all who tried to read it.

When Egypt formally asked for the Stone’s repatriation in 2003, the British Museum refused to return it, and instead gave Egypt a replica of the Stone. That replica now sits inside the National Museum in Rashid.

6) The Bust of Nefertiti (Neues Museum, Berlin)

Many people believe that the Rosetta Stone was taken by the British from Egypt, but in reality, it was taken by the British from the French, who took it from Egypt. Discovered by French soldiers in the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in 1799, this stone is perhaps the most important archaeological discovery of all time (and it remains the most visited artefact in the British Museum). Its decryption paved the way to understanding ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics (and with it most of ancient Egyptian history), which until then had been illegible to all who tried to read it.

When Egypt formally asked for the Stone’s repatriation in 2003, the British Museum refused to return it, and instead gave Egypt a replica of the Stone. That replica now sits inside the National Museum in Rashid.

6) The Bust of Nefertiti (Neues Museum, Berlin) This iconic sculpture is one of the most well-known artefacts from ancient Egypt, and it depicts an equally legendary figure: Queen Nefertiti, wife of Akhenaten, stepmother of Tutankhamun. 3,400 years ago, Akhenaten’s sculptor captured Nefertiti’s beautifully slender neck, raised chin, and level gaze, and when it was discovered in 1912 the painted sculpture was still in remarkably good condition.

At the time of its finding, excavations in Egypt were conducted under a system whereby all items discovered were split between Egypt and the foreign country sponsoring the excavation, but there was a caveat: only ‘non-unique’ items could leave the country. The controversy that surrounds this bust is that the German team that discovered it hid its true value, and thus the bust was allowed to leave Egypt and be transported to Berlin, where it remains today.

7) Colossal Figure of Ramses II (British Museum, London)

This iconic sculpture is one of the most well-known artefacts from ancient Egypt, and it depicts an equally legendary figure: Queen Nefertiti, wife of Akhenaten, stepmother of Tutankhamun. 3,400 years ago, Akhenaten’s sculptor captured Nefertiti’s beautifully slender neck, raised chin, and level gaze, and when it was discovered in 1912 the painted sculpture was still in remarkably good condition.

At the time of its finding, excavations in Egypt were conducted under a system whereby all items discovered were split between Egypt and the foreign country sponsoring the excavation, but there was a caveat: only ‘non-unique’ items could leave the country. The controversy that surrounds this bust is that the German team that discovered it hid its true value, and thus the bust was allowed to leave Egypt and be transported to Berlin, where it remains today.

7) Colossal Figure of Ramses II (British Museum, London) Also known as the Younger Memnon, this colossal torso and head once sat atop a statue of Ramses II located at his mortuary temple in Luxor. In 1798, Napoleon’s men tried extracting the statue but failed, and a couple of decades later the British succeeded in removing the upper portion of the statue (which had, long before, been damaged and detached from the rest of the body during an earthquake).

Weighing nearly 20 tonnes, the statue is the largest Egyptian sculpture in the British Museum.

8) Bust of Ankh-haf (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Also known as the Younger Memnon, this colossal torso and head once sat atop a statue of Ramses II located at his mortuary temple in Luxor. In 1798, Napoleon’s men tried extracting the statue but failed, and a couple of decades later the British succeeded in removing the upper portion of the statue (which had, long before, been damaged and detached from the rest of the body during an earthquake).

Weighing nearly 20 tonnes, the statue is the largest Egyptian sculpture in the British Museum.

8) Bust of Ankh-haf (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) This lesser known artefact is striking for its high level of realism. Its namesake, Ankh-haf, was a government official of the Old Kingdom who oversaw the building of the Great Pyramid of Giza and the Sphinx.

The bust was discovered in 1925 during an expedition by Harvard University, and in 1927 it was gifted by the Egyptian government to an American archaeologist. Perhaps fittingly given the sculpture’s realism, it now rests in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

9 & 10) Cleopatra’s Needles (London & New York)

This lesser known artefact is striking for its high level of realism. Its namesake, Ankh-haf, was a government official of the Old Kingdom who oversaw the building of the Great Pyramid of Giza and the Sphinx.

The bust was discovered in 1925 during an expedition by Harvard University, and in 1927 it was gifted by the Egyptian government to an American archaeologist. Perhaps fittingly given the sculpture’s realism, it now rests in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

9 & 10) Cleopatra’s Needles (London & New York) Despite their name, the pair of obelisks called Cleopatra’s Needles bear no relation to Queen Cleopatra herself. Instead, they were constructed during the reign of King Thutmose III of the New Kingdom, more than a thousand years before Cleopatra’s reign. During the Roman era they were moved from their original location in Heliopolis to Alexandria, where they stood for nearly two thousand years.

By the 1800s, one of the two needles had fallen. It was this needle that Muhammed Ali Pasha, in 1819, decided to gift to Britain (as he had gifted the Luxor Obelisk to France). However, the 21-meter tall obelisk was so massive that it was not actually transported to London until the reign of Ismail Pasha in 1877. It was also Ismail Pasha who, in the same year, gifted the remaining needle to the United States.

Despite their name, the pair of obelisks called Cleopatra’s Needles bear no relation to Queen Cleopatra herself. Instead, they were constructed during the reign of King Thutmose III of the New Kingdom, more than a thousand years before Cleopatra’s reign. During the Roman era they were moved from their original location in Heliopolis to Alexandria, where they stood for nearly two thousand years.

By the 1800s, one of the two needles had fallen. It was this needle that Muhammed Ali Pasha, in 1819, decided to gift to Britain (as he had gifted the Luxor Obelisk to France). However, the 21-meter tall obelisk was so massive that it was not actually transported to London until the reign of Ismail Pasha in 1877. It was also Ismail Pasha who, in the same year, gifted the remaining needle to the United States.