The Mummy & the Man Who Remembered: Shadi Abdel Salam’s Eternal Cinema

With The Mummy (1969), Shadi Abdel Salam crafted a cinematic tomb—an exquisite meditation on Egypt’s past, identity, and memory. A film that transcends time, ensuring history is never forgotten.

In 1969, in the dim hush of a screening room, Al-Mummia (The Mummy, also known as The Night of Counting the Years) unfolded like an ancient funerary text come to life. The film’s rhythms were slow and deliberate, its silences more powerful than its words. It was not the bombastic spectacle of Hollywood’s Ancient Egypt, filled with golden chariots and cartoonish pharaohs, nor was it an exercise in nostalgia. It was something else entirely—an act of cinematic archaeology. With The Mummy, Shadi Abdel Salam did not merely tell a story set in the past; he resurrected it. To this day, his first and only feature remains one of the most important films in Arab cinema —a quiet yet seismic act of remembering.

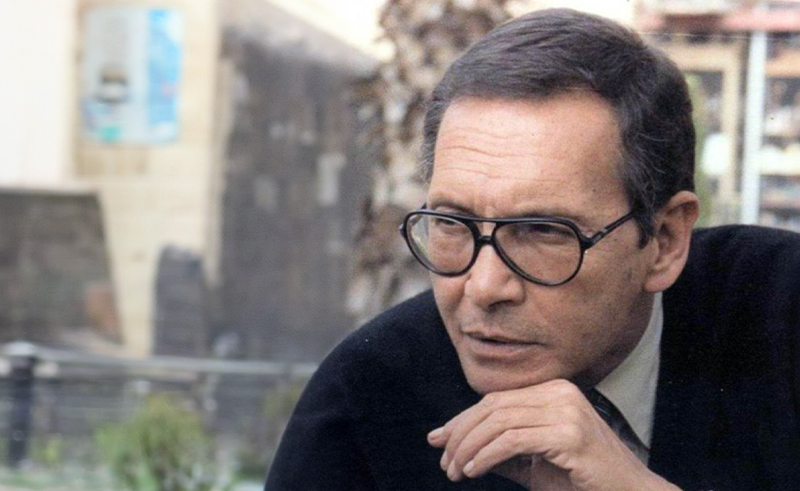

The Architect of Time

Shadi Abdel Salam was not simply a filmmaker. He was an architect of time. Born in Alexandria in 1930, he was raised in a city where Greek, Roman, and Arab legacies coexisted, but his imagination belonged to something far older. He studied architecture at Cairo University, where he became obsessed with the proportions, symmetry, and symbolism of Pharaonic structures. Buildings, he believed, were not just stone and mortar; they were containers of memory, tombs for history itself.

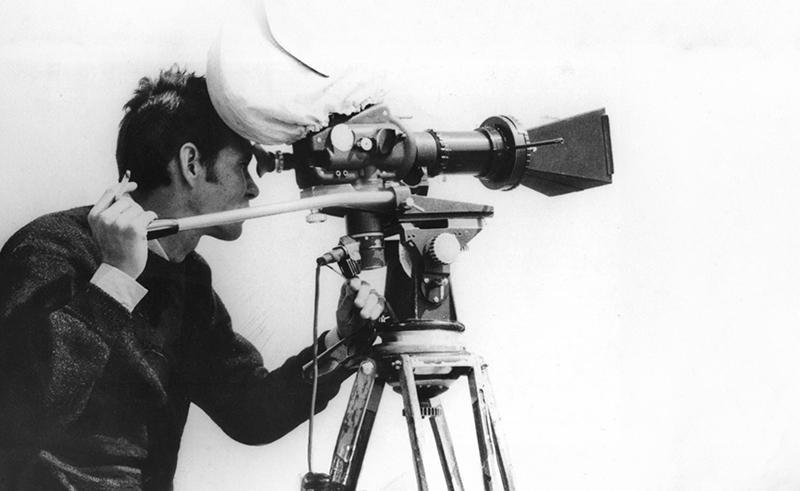

Unlike his contemporaries in Egyptian cinema, who gravitated toward neorealism or melodrama, Abdel Salam was drawn to something more monumental. His influences were far-reaching: the sculptural austerity of silent cinema, the philosophical realism of Rossellini, the montage precision of Eisenstein. His visual language was not learned from cinema but from hieroglyphs, murals, and temple carvings.

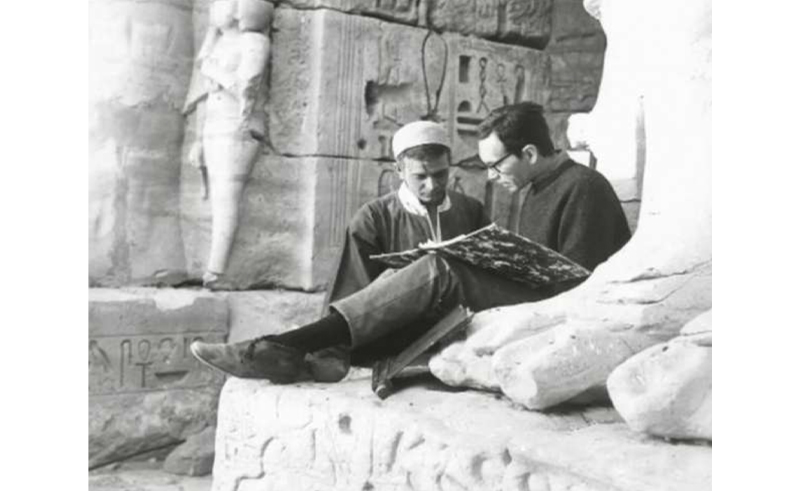

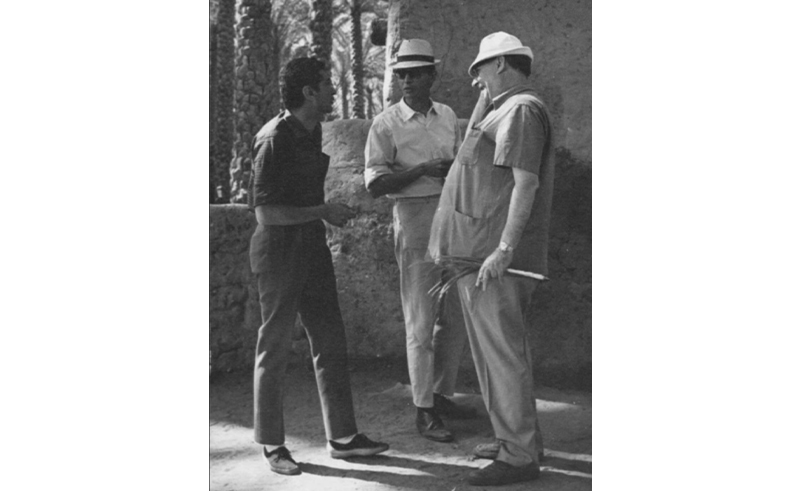

Before becoming a director, Abdel Salam was a sought-after set and costume designer. His obsessive attention to historical accuracy shaped Joseph Mankiewicz’s Cleopatra, Youssef Chahine’s Saladin the Victorious, and Jerzy Kawalerowicz’s Pharaoh. Every carved relief, every textile, every thread mattered. His work caught the eye of Roberto Rossellini, who became an ardent supporter of his filmmaking aspirations. When Abdel Salam finally stepped behind the camera, it was with the precision of a man who had spent his entire life preparing for a single, perfect composition.

The Mummy’s Curse: A Story of Looted Time

At its core, The Mummy is a ghost story, though there are no apparitions. The specters it conjures are not supernatural but historical. The film is based on the true discovery of the Deir el-Bahari Royal Cache in 1881, where the Abdel-Rasoul family—a tribe of tomb raiders in Upper Egypt—had secretly looted and sold the mummies of pharaohs for over a decade. The thieves did not see themselves as desecrators but as survivors; for them, the relics were not objects of reverence but a means to endure in a harsh landscape.

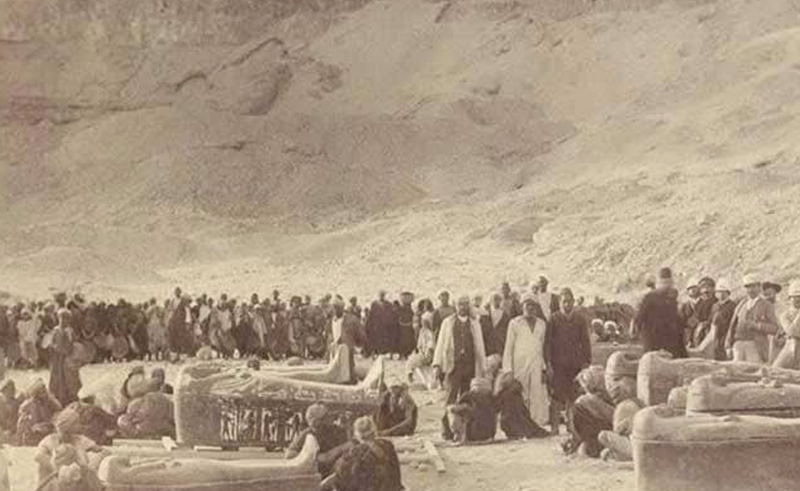

The widespread appearance of ancient Egyptian artifacts in the open market and European auctions aroused the suspicions of the government, leading French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero to launch an investigation. His inquiry ultimately revealed the cache—a hidden tomb containing more than 50 royal mummies, including Seti I, Ramesses II, and Thutmose III—one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in Egyptian history.

Abdel Salam transforms this into a moral and existential crisis. The film’s protagonist, Wanis, is the reluctant heir to this crime. When the elder of his smuggling clan dies, the secret is passed down to him. But Wanis is horrified to discover the full reality—not only are the artifacts sold to Cairo traders for money, but they are also exchanged for prostitutes brought to the village. His disgust deepens, and his refusal to participate leads to a confrontation that ultimately results in the murder of his older brother at the hands of their uncle. Wanis, however, escapes and reaches the Supreme Council of Antiquities, where he reveals everything he knows.

The weight of history is not merely a theme but a presence, pressing down on every frame. The film moves with a hypnotic stillness, its dialogue sparse, its emotions restrained. The Mummy doesn’t simply transport us back in time to depict ancient Egypt; it instead portrays the everlasting impact the past continues to have on the present, posing fundamental questions about identity, ethics, and legacy.

A Language of Stone and Silence

Abdel Salam’s use of image, sound, and space in The Mummy is unparalleled. Shot by cinematographer Abdel Aziz Fahmy, the film is composed with the precision of a Pharaonic frieze—each figure positioned as though carved in stone. The use of deep shadows, stark desert landscapes, and muted color palettes creates a world where time itself seems petrified. It is a film of whispers, of windswept sands, of men in black moving like specters through the ruins of their own history.

The film also eschews colloquial Egyptian Arabic in favor of classical Arabic, making the dialogue feel as though it had been inscribed on temple walls centuries ago. Even the pacing reflects the meditative rhythm of Egyptian ritual—each movement deliberate, each silence sacred.

Abdel Salam rejected Western cinematic tropes of Egypt. His was a land not of kitsch and spectacle but of dignity, complexity, and fatalism. His Egypt was not imagined through a foreign gaze—it was remembered.

The Book of the Dead and the Death of a Director

In the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, it is said that a person can only live again if their name is remembered. Abdel Salam weaves this concept into The Mummy in a profound way: Wanis’ brother is symbolically erased from existence when his mother declares, “I no longer know his name.” The film suggests that to forget is to die, but to remember is to grant eternity.

Abdel Salam spent the rest of his life on a single project: Akhenaten, a film about the revolutionary pharaoh who sought to redefine Egyptian religion and was ultimately erased from history. It was to be his grand statement, a meditation on power, iconoclasm, and legacy. But it was never made.

For years, Abdel Salam meticulously researched, wrote, and sketched the world of Akhenaten, determined to bring it to the screen. But the project was halted due to his declining health and lack of funding. His vision survives only in painstakingly detailed storyboards and notes, now preserved in the Bibliotheca Alexandrina.

Abdel Salam died in 1986 at the age of 56.

A Monument of Cinema

And yet, his work endures. His one film stands taller than most directors’ entire bodies of work. The Mummy was not just a film but a monument—a testament to what cinema could be when it dared to look backward not as nostalgia but as a moral imperative.

“I believe many Egyptians don’t know much about their history. I feel a deep responsibility to tell them more about it and to share my fascination with them,” Abdel Salam once said in an interview. “For me, cinema is not merely a consumerist art form for entertainment but a historical document for future generations.”

In the final scenes of The Mummy, as the pharaohs' remains are finally taken to the museum at dawn, the sun rises over the horizon. Abdel Salam films this moment like a resurrection, as though the dead are awakening once more, their names intact, their legacy intact.

The Book of the Dead says: “To speak the name of the dead is to make them live again.”

Perhaps that is Abdel Salam’s greatest achievement. He made us remember.